by Gabrielle Jean-Louis

What would life be without dreams and possibilities and fantasy? What would life be without making the unimaginable imaginable? —Naudline Pierre, 20211

Haitian American artist Naudline Pierre describes imagination as deeply important to her artistic practice, through which she can name what she wants to see and make it.2 In the 2020–22 exhibition Allied with Power: African & African Diaspora Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection at Pérez Art Museum Miami, Pierre’s painting Close Quarters (2018)and Myrlande Constant’s flag Negre Danbala Wedo (1994–2019) highlighted the tradition of Haitian women’s spiritual art that (re)imagines Haitian culture and religious iconography.3 Contemporary Caribbean feminists have explored the social realities and inner lives of Caribbean women creatives such as Pierre and Constant to underscore the deeply embedded gender politics within their experiences and how it is expressed in their work. For example, Haitian feminist critic Régine Michelle Jean-Charles analyzes the work of Haitian women creatives through a Black feminist ethic of care, one that sustains sharing, mutuality, sacrifice, and connection over competition, greed, hierarchies, and individualism.4 In her gathering (rasanblaj) of Haitian women creatives and critics, she offers “ethical imagination” as a Black feminist ethic of care and global imperative.5 This notion of ethical imagination describes how the imaginative writing and artistic practices of Haitian women are deeply personal and yet also maintain social and political significance to broader concerns such as gender equality, overlapping systems of oppression, sexual liberation, and environmentalism. Naudline Pierre’s artistic imagination and the centrality of Vodou in Constant’s work foreground how Haitian women artists participate in a tradition of Black feminist theorizing that values spiritual connections over racial and gendered hierarchies.

In Close Quarters, Pierre reimagines intimate connections to the spirits through an otherworldly iconography that belies racial, religious, and gendered hierarchies. And in so doing, she challenges the centrality of Eurocentric artistic, religious, and neocolonial conventions. Read together, Pierre’s and Constant’s works disrupt the automatic gazes of Whiteness and coloniality by invoking an alternative Haitian feminist gaze. Tina Campt defines the Black gaze as one “that forces viewers to engage blackness from a different and discomforting vantage point.”6 A Haitian feminist gaze goes one step further, forcing viewers to also explore the centrality of ethnicity, gender, and religion—and, in the case of Pierre’s and Constant’s work, a form of visual art that not only realigns assumed visions of Haitian cosmologies but also disrupts patriarchal dominance and presumed Eurocentricity. These vantage points derive from the interior worlds of Haitian women, whose social and spiritual realities are politically significant. Pierre’s Close Quarters, when considered alongside Constant’s Negre Danbala Wedo, reinforces how a Haitian feminist gaze functions as an intergenerational and geographical link between Haitian women in Haiti and those in the Haitian diaspora. This bond transcends time and space across the North Atlantic, providing a lens through which to visually think about Haitian culture and spiritual iconography.

Myrlande Constant gained the necessary sewing and beading skills to become a drapo artist as a teen, when she worked in a wedding dress factory alongside her mother, Jane Constant, and learned the advanced specifics of Vodou from her father, a notable houngan (Vodou priest). Her drapo (Vodou flag) titled Negre Danbala Wedo displays her acquired abilities in both realms as well as the deeply symbolic nature of Haitian women’s art and Afro-Caribbean religion in general. It likewise offers insight into how, across geography and generations, Haitian women artists have expressed a Black feminist ethic that sustains spiritual connections over racial and gendered hierarchies.7

Negre Danbala Wedo depicts a Vodou healing ceremony led by a houngan surrounded by three female assistants and two male devotees. Though these subjects have diverse skin tones, all of them are presumed to be of Haitian ethnicity. We see this across Constant’s oeuvre, including in Seremoni Milocan St. Nichola de Bari (Ceremony Milokan Saint Nicholas of Bari, 2014–17).8 This latter work is inspired by a Catholic chromolithograph featuring Saint Nicholas, but it includes figures of different skin color as well as incorporates Vodou imagery such as vévés (Vodou symbols). In the exhibition catalogue accompanying a show featuring both works, curator Katherine Smith notes, “Constant insists that the diversity of skin color in her works demonstrates that Vodou is universal—anyone can serve the spirits.”9 Moreover, in the case of Negre Danbala Wedo, Constant also suggests that anyone can be healed by them. The universal appeal of Vodou as a religion that can heal all Haitians challenges the legacies of neocolonial projects that suppressed and politicized Vodou in Haiti to reinforce color-class divisions. Efforts to legally suppress Vodou reflect a wider history of racial and religious division along color-class lines that further shaped Haitian national identity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

While the connections between skin color, class mobility, and religious upbringing can be traced back to the creation of a new nation after the Haitian Revolution, the politicization of religion during François Duvalier’s presidency (1957–71) became a crucial signifier of contemporary racial division.10 Carolle Charles notes that Duvalier’s political appropriation of noiriste ideology and Vodou redefined class through race, rendering the two categories interchangeable.11 Religion became a code for racial politics as Duvalier restructured the Catholic clergy to include Haitian bishops and formally recognized Vodou as authentic to contemporary Haitian national identity. Duvalier’s politicization of Vodou exacerbated preexisting racial tension between the urban Francophone mulatto elites, who were educated in Christian schools, and members of the Kreyol-speaking rural population, who were not formally educated and practiced Vodou. This division countered the notion of Haitian Pitit Guinée, or “children of Guinea,” which suggests that all Haitians have a shared sub-Saharan African cultural identity with Vodou at its cosmological center.

Though the overthrow in 1986 of Haitian president Jean-Claude Duvalier opened new democratic space, existing religious tensions remained due to the politicization of Vodou under his father, François Duvalier, who had had Vodouyizan (Vodou practitioners) within his political circle and his secret police, the Tontons Macoutes. The Catholic Church used the post-Duvalier moment, when Haitians sought to remove all remaining physical reminders of both Duvalier regimes, to spearhead a violent massacre of Vodouyizan under the broader movement of Dechoukaj (uprooting).12

Prominent houngan Max Beauvoir founded the Bòde Nasyonal at the end of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s presidency, in December 1985, to formally incorporate Vodouyizan into politics and advocate for the rural poor, but ultimately, he aided Vodou devotees during the Dechoukaj violence. Additional Vodou organizations such as Zantray (an abbreviation of “Zanfan Tradisyon Ayisen,” or the Children of Haitian Tradition) and the Lavalas Political Organization (later renamed the Struggling People’s Party when Jean-Bertrand Aristide broke from it to form the Fanmi Lavalas) would also support Vodou and its practitioners during this period.13 Constant’s Negre Danbala Wedo emerges from this broader context, and the violence embedded in these histories highlights the significance of her reimagination of color ideologies and Vodou. Her work counters such oppressive histories by centering the humanity of Vodou devotees and sustaining spiritual connection over racial hierarchy. Negre Danbala Wedo asks viewers to reconsider what assumptions they make within the context of these oppressive histories. The piece offers a snapshot of Pitit Guinée, or a world in which any Haitian—regardless of skin color and therefore class—can serve and be healed by the spirits.

© Myrlande Constant. Photo: Oriol Tarridas

Constant highlights the spiritual knowledge of the houngan and his female assistants, whose diverse skin tones suggests that in this reimagined world, Vodou is a connecting cosmological force that mediates rather than reinforces racial divisions. One of the largest and most recognizable Vodou symbols in Constant’s drapo is the snake wrapped around the male in the foreground, who appears to be the subject of the healing ceremony. It is clear the artist has depicted the supreme deity Danbala since the serpent figure is shown paired with his most favored offering: an uncooked white egg resting on a bed of white flour on a white plate (held by one of the women standing behind the houngan).14 Additionally, the houngan holds an ason, a sacred rattle used only by houngans and mambos in ceremonial services. Danbala’s association with supreme spiritual power suggests that in Constant’s reimagined world, anyone can develop deeper levels of konesans (Vodou knowledge and service). Indeed, the houngan, the subject with the most konesans to work directly with Danbala, is depicted with brown skin. His three female assistants can be interpreted as Vodou practitioners assisting in this healing ceremony due to the items they hold. The practitioner with the darkest complexion holds Danbala’s favorite offering while the practitioners with lighter skin hold white clay pitchers commonly used in Vodou ceremonies. The two men on the left have different skin tones and their empty hands and intrigued facial expressions suggest they are watching to learn more about the ceremony taking place. Across the piece, the figures’ konesans are varied and yet their skin tones do not imply any hierarchy in terms of religious knowledge. Put differently, their skin color does not suggest their level of spiritual knowledge as Vodouyizan, disrupting assumptions about color-class and religious configurations sustained throughout Haiti in the 19th and 20th centuries. Constant’s depiction of a reimagined world in which all Haitians can serve and be healed by the spirits disrupts the religious frameworks reinforced in Haiti during the same period. In so doing, Constant embodies a Black feminist ethic of care in her work that, as Régine Michelle Jean-Charles suggests, supports the possibility of spiritual connection over racial oppression.15

Naudline Pierre continues this work in the US diaspora by reimagining intimate connections to the spirits that counteract racial, religious, and gendered hierarchies through her spiritual iconography in Close Quarters. As a Haitian American and daughter of a Haitian immigrant Protestant minister, Pierre’s upbringing was intimately intertwined with the worlds of Christian doctrine and Haitian culture. She was born in Massachusetts in 1989, just a few short years before the mass migration of Haitians to the United States (the George H. W. Bush administration’s summary repatriation of Haitian “boat people” without determining their refugee status) and the second US occupation. She uses her work to imagine alternative possibilities that—outside the scope of but still influenced by her Haitian American national identity and religious upbringing—instead serve as points of departure.16

Jean-Charles’s notion of the “ethical imagination” is useful here as a lens through which to examine Pierre’s work. It foregrounds the deeply personal nature of her imaginative artistic practice but has broader social and political significance in terms of racial, religious, and gendered oppressions. Further, Pierre situates herself within the work in the form of a feminine central protagonist who is, in effect, her alter ego. “I’m making work for myself, I’m making work to heal myself, to understand my experience, but also to connect to something bigger than me.”17 Her artistic ethical imagination fosters a practice of refusal in which she opposes hegemonic structures rooted in patriarchal hierarchy and individualism. Pierre’s work embodies a Black feminist care ethic by focusing on gendered concerns such as agency, protection, and her feminine avatar’s connection to the spirits. Indeed, her work explores the possibilities that arise when Black women can imagine alternative realities that center their pleasure and power, like how Constant imagines a Pitit Guinée, or a world in which any Haitian can serve and be healed by the spirits, despite long-standing contemporary racial politics that have suppressed Vodou in favor of Eurocentric religions.

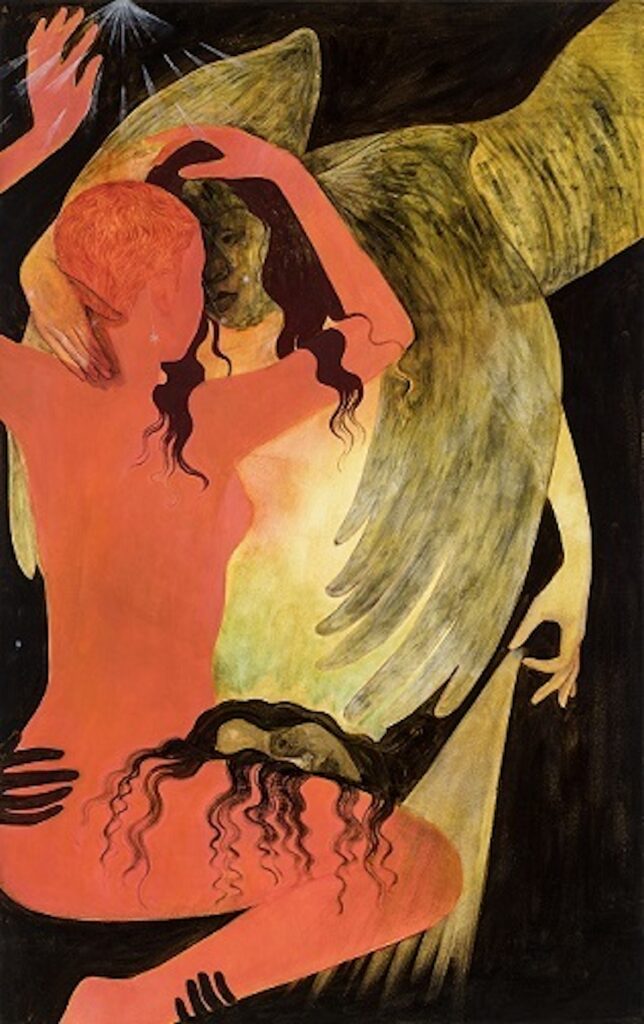

In Close Quarters, Pierre presents three ethereal feminine subjects existing in a world devoid of the racial, religious, and gendered hierarchies that structure our own realities. Just as Myrlande Constant contends with the racial politics that limit Vodou’s accessibility to a wider Haitian audience, Pierre reconsiders US-based racial hierarchies that limit the legibility of her work as a Haitian American artist. She achieves this sort of world-building through color and composition that force viewers to adopt an alternative Haitian feminist gaze. As she explains, “Using color to disrupt what is expected is really important to the work and to me. But it is also about allowing these characters, especially the central [one] to take up and to reimagine herself so she appears and reappears in different colors and different forms and I think that is hinting towards this idea of multiplicity and being allowed to be in many forms or resisting capture.”18 The skin tones of the figures in Close Quarters are yellow, red, and black, characteristic of how, across her oeuvre, she uses color to counter racial hierarchies, challenging viewers to confront the alternative configurations of race existing in her ethereal realm. She sees her use of nonrealistic skin tones as a way of disconnecting her work from our reality. The central protagonist in the piece, who resists capture, also appears in Blessed are the Blessed (2018) and twice in Dont You Let Me Down Dont You Let Me Go (2021).19 Pierre connects her avatar to spiritual entities that surround her on the canvas by positioning them in an intimate embrace or offering a tender touch. The line “In a moment of tenderness, the future seems possible,” from Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, brings to mind Pierre’s emphasis on touch and, in particular, the moments in which her avatar and the spirits connect.20 She questions what they feel and what they think, suggesting that in her reimagined world, feminine subjects and the spirits are personally linked rather than hierarchically distant as Eurocentric religions suggest. We see this further in the composition of Close Quarters, which evokes Christian depictions of the Holy Trinity.

Although Pierre does not limit her work to a singular religious form, whether it be Christianity or Vodou, her evocation of the Holy Trinity in Close Quarters speaks not only to her identity and world-building but also to her engagement with a Haitian feminist tradition of imagination as an ethical imperative.21 Briefly identifying their resemblance allows for Pierre’s Black feminist care ethic to be better understood. Within Christian doctrine, the Holy Trinity symbolizes the unity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, often depicted as three males configured hierarchically. Pierre imagines an alternative trinity composed of three entwined female figures joined by their hands, hair, and a central beam of light. Yet by compositionally reimagining the underlying themes of power present in the Holy Trinity, she rejects its traditionally masculine nature. Her three feminine figures are not configured in a way that makes them clearly separate from the rest of the piece or that implies a sense of dominance; instead, they melt into each other in such a way that one figure does not reign over another. Pierre’s rejection of Eurocentric masculine spiritual dominance in favor of a Haitian feminist gaze enables viewers to experience a spiritual relationship that does not assert the gender-based power of one subject over another.

Expanding on her intentional use of imagination as an ethical imperative to sustain realities different from our own, Pierre refers to Saidiya Hartman’s “waywardness.”22 She understands waywardness in her artwork to be “an attempt to elude capture by never settling,” in the sense that settling would mean configuring race, gender, and religion in the easy, unimaginative forms that reflect our reality. Her ethical imagination as a practice of refusal allows for her avatar and her work to avoid capture or containment within the same fixed hegemonic categories that she rejects. Instead, Pierre offers a Haitian feminist gaze that sustains alternative realities in which feminine subjects have agency and are spiritually protected and free from oppressive race-based and gender politics. Pierre continues this Haitian feminist work of theorizing that intergenerationally and geographically links her to Myrlande Constant but that also takes shape across a network of global Black feminist artists, creatives, and thinkers.

Naudline Pierre’s Close Quarters, when read alongside Myrlande Constant’s Negre Danbala Wedo, engages a tradition of Haitian women’s art that upends religious iconography. The necessity to engage a Haitian feminist gaze as a mode of survival involves displaying depictions of the spiritual world through the lens of Black women so that Afro-Caribbean spirituality can continue to be honored despite eradicative efforts by neocolonial powers. When Constant and Pierre invoke this gaze, they cut across time and space, linking generations of Haitian women artists across Haiti and its diaspora. This transcendent bond, celebrated in Allied with Power, gives voice to the silenced Afro-Caribbean artists.

Gabrielle Jean-Louis, a PhD student in the Department of English at the University of Miami, specializes in contemporary Haitian women’s literary and visual culture. Her research delves into the presentation of healing methodologies within intimate Black diasporic feminine spaces. Focusing on works by authors such as Edwidge Danticat, Francesca Momplaisir, and Debbie Rigaud, and visual artists such as Myrlande Constant, Naudline Pierre, and Kathia St. Hilaire, she explores how diasporic communities provide Haitian female subjects with avenues for spiritual healing through interfaith dialogues, exposure to African spiritual practices, and Western psychotherapy. Jean-Louis has presented her research at the Modern Language Association Annual Convention, American Studies Association Annual Meeting, and the West Indian Literature Conference.

- CAAM Salon: Naudline Pierre and Taylor Renee, California African American Museum, YouTube video, 26:42, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJbvfuEExvw.

- CAAM Salon, 52:57.

- Allied with Power: African & African Diaspora Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, Pérez Art Museum Miami, November 7, 2020–February 6, 2022.

- Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, Looking for Other Worlds: Black Feminism and Haitian Fiction (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022), p. 26.

- Jean-Charles, Looking for Other Worlds, p. 26. Jean-Charles employs Haitian feminist thinker Gina Athena Ulysse’s notion of rasanblaj as a theoretical framework for analyzing insular and diasporic Haitian feminism. See Ulysse, “Introduction,” Caribbean Rasanblaj 12, no. 1–2 (2015), hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-121-caribbean-rasanblaj/121-introduction. See also Ulysse, “Why Rasanblaj, Why Now? New Salutations to the Four Cardinal Points in Haitian Studies,” Journal of Haitian Studies 23, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 58–80.

- Tina M. Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), p. 8.

- It should be noted that as I later examine the racial hierarchies embedded in contemporary Haitian color-class configurations, I do not conflate race and colorism here. Instead, I use the term “racial hierarchies” to succinctly address a wider history of colorism in Haiti, one dating back to colonial Saint-Domingue. Carolle Charles discusses the importance of this critical move in her chapter “Coloring the Social Structure,” in which she analyzes François Duvalier’s racial politics, which were informed by 19th-century color ideologies. Her text effectively models how to think through contemporary Haitian racial politics influenced by colorism. See Charles, “Coloring the Social Structure: Racial Politics during the Duvalierist Dictatorial Regime of 1957–87,” in Race, Colonialism, and Social Transformation in Latin America and the Caribbean, ed. Jerome Branche (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008): p. 2.

- Myrlande Constant. Seremoni Milocan St. Nichola de Bari (Ceremony Milokan Saint Nicholas of Bari), 2014–17. Sequins and beads on cotton. Collection of Sheldon Inwentash and Lynn Factor.

- Katherine Smith, “Vodou in the Life and Work of Myrlande Constant: Labor, Gender, and the Lwa,” chap. 2 in Myrlande Constant: The Work of Radiance, ed. Katherine Smith and Jerry Philogene, exh. cat. (Seattle: University of Washington Press in association with the Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2022).

- For brevity, my analysis of color ideologies, racial politics, and Vodou in contemporary Haiti begins with François Duvalier’s presidency. The 19th-century Haitian government enacting the Code Pénal de la République d’Haïti (Haitian Penal Code) and US occupants during the first US occupation (1915–34) banning Vodou are earlier instances in which Vodou was legally suppressed because of color-class configurations. See Kate Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); and Kate Ramsey, “Vodouyizan Protest an Amendment to the Constitution of Haiti,” Journal of Haitian Studies 19, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 272–81. See also Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation & the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), pp. 156–57.

- Charles, “Coloring the Social Structure,” p. 2. Noirisme, a cultural and political movement in Haiti that emerged in the early 20th century, emphasized the importance of African heritage and Black identity in Haitian society. The movement sought to promote Black pride, resist the legacy of colonialism, and counteract the influence of the country’s mulatto elite. Noiristes advocated for the recognition and celebration of African roots and cultural contributions, aiming to uplift the majority Black population and redefine national identity in a way that acknowledges and values their experiences and history. Jean Price Mars’s foundational ethnography Ainsi parla l’oncle (So Spoke the Uncle, 1928) strongly influenced the basis of noiriste ideologies. See J. Michael Dash, Literature and Ideology in Haiti, 1915–1961 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1981).

- J. Michael Dash writes, “Dechoukaj took the form of destroying the headquarters of the Tonton Macoutes, the homes of Duvalier officials, the BMW dealership of Ernest Bennett, and ultimately the mausoleum of the Duvalier family in the national cemetery.” Dash, “True Dechoukaj: Uprooting Bovarysme in Post-Duvalier Haiti,” in Politics and Power in Haiti, ed. Kate Quinn and Paul Sutton (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 33.

- See Markel Thylefors, “‘Modernizing God’ in Haitian Vodou? Reflections on Olowoum and Reafricanization in Haiti,” Anthropos 103, no. 1 (2008): pp. 113–25.

- Vodou practitioners and scholars of the religion agree that Danbala’s offerings include white food and textiles. Patrick Bellegarde-Smith and Claudine Michel write, “The wizened old ‘man’ Danbala (as if he were a person) is represented on altars by white cloth, refined white flour, sweet almond syrup, and eggs.” Bellegarde-Smith and Michel, “Danbala/Ayida as Cosmic Prism: The Lwa as Trope for Understanding Metaphysics in Haitian Vodou and Beyond,” Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 4 (2013): p. 472, https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrireli.1.4.0458.

- Jean-Charles, Looking for Other Worlds.

- She sees religious iconography as a tool like color, texture, and composition. “I was using it [religious iconography] to create a sense of my own personal mythology. Grappling with my own experiences with my upbringing, and sort of my own experience with what religion can look like across the diaspora and across my own personal diaspora . . . I found that my earliest inspirations and connections to art came from religious artwork serving as a natural starting point and [in my practice, I] expanded it to fit what I want to see rather than what’s been given to me.” CAAM Salon, 33:58.

- CAAM Salon, 33:58.

- CAAM Salon, 42:20.

- See “Naudline Pierre,” Prospect.5: Yesterday we said tomorrow, exhibition website, https://www.prospect5.org/artists/naudline-pierre.

- Although Hartman’s work was published a year after Pierre completed Close Quarters, I suggest that “Wayward Lives Beautiful Experiences” informs and names the artist’s earlier practices. See Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019).

- CAAM Salon, 42:20. Also, when asked if Vodou influences her work as a Haitian American artist, she responds, “I think it’s part of the lineage of being in this body, but I am more so interested in creating something of my own cobbled together with what I was given.” Ibid., 51:09.

- Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.