by Yoán Moreno

But I am the one who must stop myself from giving a name to the thing. The name is an accretion, and blocks contact with the thing.

— Clarice Lispector1

This text is about “chaotic figuration” and “creole concrete,” a perspectival distinction in abstract art that I came to see by writing about my interactions with Tomás Esson’s Patrona (2019) and Guido Llinás’s Pintura Roja (1961) in Allied with Power at Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM).2 The distinction—perspectival because it varies from viewer to viewer and even within a single viewer, which is to say it is a spectral rather than a binary distinction—is based on the effect of a so-called abstract work on a viewer: chaotic figuration drives you toward identity, creole concrete, away from it.

A chaotic figuration is an abstraction whose limit is decoding, a process that settles the viewer’s anxious need to name and organize what they at first do not recognize. This is the drive toward identity. A creole concrete, on the other hand, is an “abstraction” without such a limit—it has no code to check against, and so no name that will settle the viewer’s experience of ambiguity, driving them toward production instead of organization. This is the drive toward becoming. The one is a wall, the other a portal; if the first seems like a womb, it is only the second that will bear. But as I said, the distinction is spectral. A single piece can be both a creole concrete and a chaotic figuration, but typically only in that order—if an identity is assigned, a name given to the creole concrete, the fecundity of its namelessness disappears. Once the piece becomes a chaotic figuration, its generative possibilities die. Only a shocking alienation or a painful defection could bring them back from the name.

Name

The ultimate objective of this text is to help us feel and value the nameless. This is the path offered by the difference—the namelessness—of a creole concrete. But we must first untie a certain knot that keeps us from viewing Pintura Roja, for example, as “concrete” rather than abstract. So we must first critique the word “abstract,” which we use imprecisely in discussing “nonfigurative” or “nonrepresentational” artworks. We have been using it backwards to label works that do not recall a thing (in the world), that are so nonrepresentational as to be unique (in the world), as to be non-referential (within the world)—as to paralyze your ability to recognize (the world). We err diametrically when we call these things “abstract,” for abstractions are precisely the names we use to order and reference things in the world by eliminating their differences, by ignoring the fact that those differences are what resist indexation and complicate recognition and, thus, decipherment.

Abstraction is the process of theoretically equalizing concrete differences under a single name. Nietzsche gave the example of a leaf: “Every concept originates through our equating what is unequal. No leaf ever wholly equals another, and the concept ‘leaf’ is formed through an arbitrary abstraction from these individual differences.”3 If we bring this to bear upon art, we see that it is representational art, then, that is abstract. It is the still life and the landscape that are abstractions, the drawing of the leaf that swallows up all the real leaves. Figurative or representational works are abstract in that it is these works that most obviously reduce the unruly and ambiguous concrete differences of the world into recognizable types, into names for control—names that inhibit “contact with the thing.” The effect of these truly abstract works is to accustom the viewer to a clarity and an ease of comprehension, to a sense of control.

It is the same sense of clarity—and here arise the stakes—that the founders and managers of the “new world” fought for when faced with the concrete differences—the unruly and ambiguous marks—of the creoles that began to bleed from the people of colonial Earth. One letter, law, and study at a time, the managers of categories—the races—fought to abstract the creoles they could not stop from becoming. In the Martinique of the late eighteenth century, for instance, Moreau de Saint-Méry published a “systematic classification of human variety in the [French] colonies” that included “an exhaustive tabular, arithmetic, and narrative typology of ‘nuances of the skin’ along a continuum between white and black” that was “fixated on the one difference that carried political consequences in Saint-Domingue—that between white and non-white, or ‘sang-mêlé’ (mixed blood).”4 Black and white were simple enough, but it was the wavy categorical lines of “non-white” that kept Moreau up, driving him to pursue a control in the realm of mathematics, of the quantified abstract. But creoles, ambiguous and unruly in representation, that is, in reference to categories, resist abstraction—they are as worldly as it gets, and as such, eminently concrete.5 Originally thought by people like Moreau to be the “endpoint of reproduction,”6 creole concretes turn out to be the most fertile forms of art. When they aren’t simply in costume, that is.

Chaotic Figuration

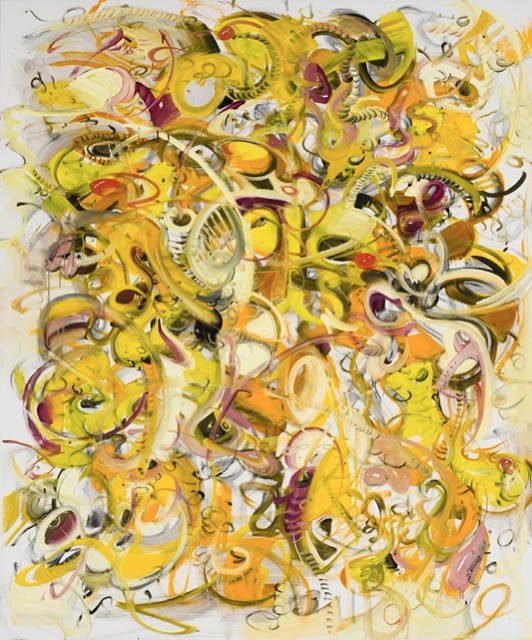

In the typical language of the “abstract,” Esson’s Patrona may appear to be limitless despite its rectangular frame and allusive title. The overwhelmingly yellow scrawl—I first see it as a giant piss stain on the wall (as opposed to the glittering guts or angelic aura of Cachita/Ochún). Had that image held on to me—for it is not my thought exactly, but rather the force of the painting forming and deforming thoughts in me—such an impression could have served as a portal to a stream of new images and sensations, away from fixity and identity for the painting. But that would depend on how much you know about Tomás Esson (and hence, the perspectival nature of the distinction driving this text).

Knowing what I know—the clarity of what I know about Esson—seals off the potential of Patrona, takes all of its force and subjects it to a code. It reduces the painting to a set of names that allows me to make sense of it—to recognize it—in a process of reinstating it to an unthinking order, to stable identity. At stake is the novelty of our hallucinations, for recognition—even if it must be done through decipherment, as it will be with Esson’s painting—always reinstates order. As Hialeahn theorist José Esteban Muñoz (who was above all concerned with the future) wrote: “Evidencing protocols [in the study of art, for instance,] often fail to enact real hermeneutical inquiry and instead opt to reinstate that which is known in advance.”7 This is what happens when we decipher a Monet; we restore the blurry vision to focused order by naming its rivers, boats, suns, and trees on the basis of our arguments about line, form, texture, and color. This act—engaging the piece on the level of abstraction as the path to (clearer abstractions of) its referents—is what kills the potential of a work to take you places of learning. Learning, as production, is sacrificed for knowledge as recovery. Muñoz continues: “Thus, practices of knowledge production that are content to merely cull selectively from the past, while striking the pose of a positivist undertaking or empirical knowledge retrieval, often nullify the political imagination.”8 For there can be no creative spark if your task is merely to put something back in order; in fact, your comprehension snuffs out that flame.

But it is not all in the hands of the viewer. It is usually the artist who places the limit. This is the case with Esson, who has explicitly stated that he is obsessed with hair and five body parts. “[H]air is the problem through which my work has evolved and sexuality is the theme that dominates it.”9 Knowing this, the soaked spirals of Patrona become pubic hair; the hairs become obvious. Before we are even able to recover from this first decipherment, we are burdened with the rest of the code (the five body parts), which sits in easy relation to pubic hair: “Vagina, Breast, Mouth, Anus, and Penis.”10 Given these five discrete categories that Esson holds as such, Patrona becomes a messy still life––a chaotic figuration––of them. Even if we restrict ourselves to the upper-left corner of the work, we see little black swirls of pubic hair, a pale pink-purple thing surrounded by rays (or hairs) that recalls an anus floating over a much larger hole of the same kind—a vagina, a bearded mouth, or a gaping anus. (It also looks like an eye, but Esson’s elements foreclose that ambiguity.) To the lower right of this figure—and scattered throughout—there is an ejaculating trunk, or penis. The breast is missing, but the point is that I am already looking for it, anxious to reinstate “that which is known in advance.” But if this chaotic figuration is a messy still life (of penises, vaginas, anuses, pubes, and mouths)—and I have already said that it is, and that it is representational art that is abstract—then Patrona is at least one dripping in LSD, we want to say.11 But I find it, ultimately, to be translatable and intelligible, doing to me what all chaotic figurations must: turning me into a paleographer.

Perhaps, if you had not read Esson’s interviews, if your perspective were another, Patrona could possess the ambiguity—indecipherability—necessary to generate new thoughts (learning and creation) in you. But seeing his painting on the wall with his preoccupations in mind puts you in the mode of recognition, which Deleuze, for instance, has argued all over his work is precisely that which stifles thought (or, as Muñoz says, “nullifies the political imagination”).12 The issue at stake with Esson’s Patrona is that it is in actuality representational art, a work with an end. It’s a tab of acid that turns out to be nothing but paper—and settling on this thought is what “blocks contact with the thing.”

Creole Concrete

For the new—in other words, difference—calls forth forces in thought which are not the forces of recognition, today or tomorrow, but the powers of a completely other model, from an unrecognized and unrecognizable terra incognita.

—Gilles Deleuze13

What could arise from contact with the nameless is unknown; it is precisely something—some things, in fact—beyond recognition. From one concrete, another, another, and another—a proliferation of misrecognition, of creation. In facing Pintura Roja, we are not afforded the movement from the multiple affective experience that generates to the single conceptual one that stifles. I, for one, cannot settle the feeling the painting generates (“block contact”) by deciphering its references (for he gives us no sacred elements). Llinás’s piece is rough; it brings alarm to this body of mine, concern even. My mind walks the path of its training in recognition: the red is blood, the giant suture running down the canvas is a scar, the slices taken out of the red on black reveal the white of teeth behind a cleft or cut lip. Analogy tells me that this is the portrait of a bleeding Michael K. Williams looking in the mirror (perhaps an image from The Wire). It is difficult to avoid naming—and Lispector says it is we who must resist doing so—but here, since there is no code to check against (that I am aware of), there is nothing to stop the immediate occurrence of another image, and another: Williams’s face warps into a bleeding knee, and so on. Eventually the images become iterations of wounds, mine and those I have licked for others. And as I begin to settle on a name—wound—I am starting to turn Llinás’s painting into a chaotic figuration; I am coding it and limiting its capacity to create through me, to push me into a new vision, toward a new rhythm, reducing it to the reproduction of my memories and repertoires, walling up its futurities with my pasts.

And if I were to settle totally on this name, to declare its identity as is the Western tradition, to make everything a representation of something else—“Pintura Roja is a wound”—then it would seal our fate, replacing a generative relationship for a decoding, a relation of making for one of unmaking, a portal for a wall. Then the race through history would commence, for only unmaking requires proof: my interaction with Pintura Roja would become about organization, putting it where it goes in the gallery of representations.14 I would locate it in time and space: Cuba, 1961, the intensification of the Revolution after the hellishly unequal and violent 1950s. I would locate it in the artist’s life, just after a vanguard career as the lead Onceño—ignored, yearning for the recognition he gave to the Europeans—and just before Llinás’s self-exile to Paris for the remainder of his life.15 If I catch hold of a name—if I impose a name with the only thesis we have been trained to make, “X is Y”—I will use it to settle the feelings of concern and alarm that are running through me like the instrument I am and generating images: some remembered, some unknown, all of them effects of my relationship with a painting that has seized and drugged me with unruly and ambiguous futures. I will use that name to settle the feeling that not only do I have no idea what X is, but that also I am not quite sure what X is doing to me. In fact, I am not even sure who I am when I feel the namelessness of X. Because Pintura Roja is a thing whose accent doesn’t match its face and, instead of pulling out ID, is already grabbing me from above, putting rhythms no one has ever sung to me into my hands.

Yoán Moreno is a teacher, scholar, musician, and translator. Born and raised in Miami, Florida, he earned a BA in English from Florida International University, an MA in English from Loyola Marymount University, and he is currently pursuing a PhD in Literary, Cultural, and Linguistic Studies at the University of Miami. Moreno drums and composes for the bands Copán and Navaja (Lenta). He also runs the community archive of interviews with Miamians Who Invited Miami.

- Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G. H., trans. Idra Novey (New York: New Directions, 2012), p. 145.

- The exhibition Allied with Power: African and African Diaspora Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection opened at PAMM on November 7, 2020, and closed on February 6, 2022.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, “From On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense [1873],” in The Portable Nietzsche, ed. and trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Viking Press, 1954), p. 46.

- Doris Garraway, “Race, Reproduction and Family Romance in Moreau de Saint-Méry’s Description . . . de la partie française de l’isle de Saint-Domingue,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 2, 2005): p. 227.

- Or has anyone, across the centuries and languages of accusation, declaration, drift, and study, settled the question of what the creole is?

- Garraway, “Race, Reproduction and Family Romance,” p. 230.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p. 27.

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, p. 27.

- Gean Moreno, “Hairy Monsters and Flying Talismans: Interview with Tomás Esson,” in Tomás Esson: The GOAT, ed.Gean Moreno, exh. cat. (Miami: Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, 2021), p. 183.

- Ana Fernández, “El Bicho: Interview with Tomás Esson,” in Moreno, Tomás Esson, p. 243.

- Patrona may very well represent a “creole concrete,” i.e., a more productively hallucinatory experience, for someone without an awareness of this code.

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, p. 27.

- Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition (1968), trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 136

- It is not by coincidence that the protagonist of Lispector’s novel deals at such length with the practices of housekeeping and arrangement.

- I would be driven to prove all of these things, pulling quotations from 1954 like this one: “In any other country on Earth, the magnificent exhibition that the group of artists known as Los Once [whose members were known as Onceños] has just had at the Círculo de Bellas Artes would have been considered an event of great artistic magnitude, a milestone in the development of our national culture. But in Cuba, where the public’s attention is absorbed in politics, baseball, and sugar, an exhibition like this one is condemned to indifference and to the commentary of friends and a few critics, if that.” Mario Carreño, “Grupo de Los Once,” in Espacios Críticos Habaneros del Arte Cubano: La Década de 1950, ed. Luz Merino Acosta (Havana: Ediciones Unión, 2015), vol. 1, p. 349. My translation.