by Sade Gordon

Eusebia Cosme (1908–1976), Faith Ringgold (b. 1930), Imna Arroyo (b. 1951), Betty Blayton (1937–2016), Sana Musasama (b. 1957), Augusta Savage (1892–1962), Anita Bush (1883–1974), Etta Moten Barnett (1901–2004), Marian Anderson (1897–1993), Howardena Pindell (b. 1943), Xenobia Bailey (b. 1955), Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968), Oya, Oshun—Our Mothers1

Firelei Báez’s untitled mural from her 2018 exhibition Joy Out of the Fire at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture explores the active creative potential in envisioning connections between Black female visual and performing artists, pointing toward a discursive network of community that transcends time, space, and Western ways of knowing and being in the world. This work—an inHarlem project presented by the Studio Museum in Harlem in partnership with the Schomburg Center—critiques the masculinist ideologies inherent within the Center’s original project of collecting a Black world.2 Simultaneously, it disrupts linearity to realize Alice Walker’s vision of her mother’s garden.3 In her attempt to expand the limitations of Arturo Schomburg’s project, Báez’s art goes beyond granting honor and recognition to serve as the medium that visualizes a borderless, liberatory, and global space for the creative spirits of our mothers, providing them with “something, for the woman who literally covered the holes in our walls with sunflowers.”4

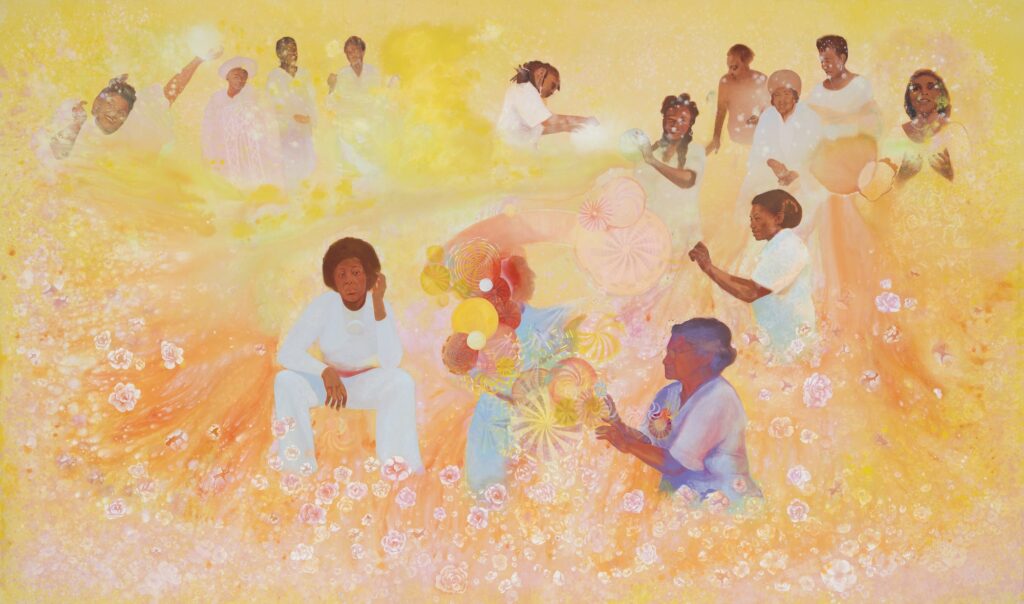

The mural features figurations of fifteen women5 in an encompassing cloud of yellow and orange hues that playfully blur together and mark the scene as something outside of any tangible, temporal realm. This undefined sphere is the mythical space of the spirit, a space that defies the rigid logics of time, place, and border; the reds and yellows invoke the Orishas, the female deities of Afro-Caribbean and Yoruba religious tradition, to do this work. The women are like sweet apparitions, their bodies playing with and blending into the mass of colors, flowers, and spirit surrounding them to varying degrees, making it seem as if they are suspended in air. Their smiles and movements mark this space as a place of pure joy and liberation. They seem to tease the onlooker with their audacity to be seen, to play, to exude joy, and to exist in their aerial garden, beyond the accepted borders of the natural world.

In contrast, the distinct detailing of each figure complicates the visual tale. These figurations are not simply abstract representations in an unnamed Afro-female collective but rather portraits of actual women whose existences are documented within the archival collections of the Schomburg Center. This mural goes unnamed, just as those depicted often are in the discourses to which they have devoted their life’s work. By naming these women in an unnamed context, Báez emphasizes how movements of the feminine are devalued and go unrecognized in real-world spaces. The spectator is made to consider who exactly shows up, rather than the definition of the mural space they inhabit, gesturing away from Western geographic narratives that would deny the existence of spaces that cannot be definitively named, placed, or located within the natural world. In defying borders, and rejecting the rigid limitations encoded within a Western rationalist expression, Baez turns toward the undefinable spiritual imaginary of aerial space. Therefore, the mural breaks form to display multilayered meanings that express compound and, at times, contradicting truths.

Importantly, these women are not periphery to a larger picture. Their contributions make the piece, emphasizing their agency in shaping both community spaces through their real-world creative activism as well as the imaginary space of the canvas. This focus is reflected in the playful imagery. The orbs of the scenery move through their hands as if they are shaping the murals’ contours as opposed to being shaped by or placed within them as afterthoughts. Here, Báez credits the women as co-creators of the art, as a network for creative motivation. The scene reimagines a cross-cultural unity attempted in the Schomburg Center’s original project; however, the space allows for a liberatory Black womanhood that the Center’s project is unable to accommodate.

By including women of both Afro-Latin and African American ancestry, Báez forms a meeting space for a feminine global network that theorizes these women as interlocutors who have shared spaces across time, despite their varying national contexts and forms of cultural expression. The break with generational boundaries and chronological placement, in particular, disrupts time and natural order, joining these women together beyond even the borders of life and death. For instance, Eusebia Cosme is placed next to Faith Ringgold, who was born at the time Cosme would have been at the height of her career. These entangled legacies work to restore memory of the feminine forgotten in Arturo Schomburg’s original project. With her border of flowers, by envisioning them as a community, Baez bestows upon these women more than individual recognition.

In invoking the feminine Orishas, Oshun and Oya, attributed to Yoruba and Afro-Caribbean traditions, Báez taps into their spiritual power through ritual, an act practitioners take to change the basic order of reality and address community issues. This is because the Orishas were not only the mysterious authenticators of Yoruba activities but also a threat in their ability to cause disorder and drastic dynamic change.6 Thus, in ritual, Baez taps into this power to disturb order and re-envision Black female connection through an African-descended spiritual knowledge. The positioning of the women as floating, dancing, and at play with the yellows and reds, swirling in an endless background of movement marks them as the children of Oshun and Oya. They dance in ritual for their mother of water, Oshun, in billows of her favorite color as they are warmed by the fire, and they are brightened by the winds of their other mother, Oya, who is depicted at the center of the mural. As Judith Gleason notes:

The goddess Oya, Orisha Oya, of African origin, manifests herself in various natural forms: wind, which can be playful and refreshing, but especially strong wind, escalating into tornadoes; fire both generative and all-enveloping, but especially quick, nervy, directional lightning; the river Niger, especially that part of it that runs around the island of Jebba, Oya’s island in Nupe, a place of transit on the way out of the Yoruba world, this world, and on to the next. She also takes the form of an African buffalo, which appreciates muddy wallows; but except for horns seen on her altars, because her species is missing in the New World, few have seen her this way over here. That figures: for Oya has the habit of becoming invisible, only to reappear somewhere else where you least expect her.7

It is Oya’s dynamism, her refusal to be defined, that takes us to the sky, into the storm of the aerial space referred to in the title. The women tap into this spiritual energy of these Orishas as sources for creation as they shape the mythical, aerial space of the canvas that is evocative of Ogun, the heaven in which the Orishas dwell. As she paints, Báez’s hand ritually dances along as a child of all these mothers, serving as the medium summoning all her mothers and their mothers before her to the generative source of the Orishas.

With this, Báez answers Alice Walker’s search. Walker’s essay opens with a reflection on the spiritual richness of Black women, describing it as something intense, deep, and unconscious that has historically been beat down in Black women. “In the selfless abstractions their bodies became to the men who used them, they became more than ‘sexual objects,’ more even than mere women: they became ‘Saints.’ Instead of being perceived as whole persons, their bodies became shrines: what was thought to be their minds became temples suitable for worship.”8 Although she writes from a primarily African American context, Walker’s project, like Báez’s, reflects on how the creative spirituality of Black women and their bodies have been used as generative forces without acknowledgment of their efforts, energy, or sacrifices.

The depicted women have selflessly given their spirit in their work as cultural activists and revolutionaries for the Black world, and yet many of them have gone underappreciated, have been lost in the records of history. This is despite having laid the foundation for future cultural workers and working alongside men who have been lauded for similar efforts. With her artistic technique of juxtaposing the detailed and the blurred, Báez takes what the record has made an abstraction and enables these “Saints” to be whole persons liberated through the power of the Orishas. Although the mural could present these figures as a pantheon of “Saints,” or Orishas, in a mythical Black women heaven, Báez does not allow this reduction, granting them instead the honor of a name and a space in which they can express the full extent of their spirituality. Walker’s description of Sainthood or motherhood counters this, framing it as an abusive trap of limits and rigid borders: “These crazy Saints stared out at the world, wildly, like lunatics—or quietly, like suicides; and the ‘God’ that was in their gaze was as mute as a great stone.”9 However, the “Saints,” “Gods,” and mothers in Báez’s visualization exist without containment. They are not quiet or subdued, as is signaled by the robust colors; indeed, these women are able to be loud, bold, and creative devotees to their fullest potential.

Walker also turns to her own pantheon of “Saints,” revealing their identity to be artistic foremothers who were unable to tap into their spirit freely. “For these grandmothers and mothers of ours were not Saints, but Artists; driven to a numb and bleeding madness by the springs of creativity in them for which there was no release. They were Creators, who lived lives of spiritual waste, because they were so rich in spirituality—which is the basis of Art—that the strain of enduring their unused and unwanted talent drove them insane.”10

Here, the limitations and fragmentation of an African-originated, feminine, artistic spirit as well as the fragmentation of diaspora are a madness. Although the need for a united lineage as part of the liberatory garden space is not stated, it is suggested in Walker’s own turn toward literary mothers, like Harlem Renaissance writers Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen, as a source of creative spirit. Báez’s ritual visioning awakens and restores Black women internationally to a lineage that has been broken, to their mothers’ gardens, reflecting spiritualist beliefs of female rites “restoring ancestral ties where lineages have been segmented or where, in urban settings, lineage fragments see return to their roots.”11

By placing these women in conversation with one another and rooting them in an African spiritual tradition that has been broken and fragmented—by colonization and official narratives of history—Baez reminds us of and allows space for the role of the Black female artist. It is role carried out through the ritual tradition of continually renegotiating official narratives through art, memory, and linkage to the spiritual power of foremothers. In ritual, members of the feminine global network of cultural workers become marked as the legitimate heirs to and devotees of a lineage of creative revolutionaries. This is the garden that Walker seeks and the space that Báez creates with her mural.

Sade Gordon is a third-year PhD student in the Department of English at the University of Miami. Her interest is in Caribbean space, migration and Afro-Diasporic feminisms, and through engagement with decolonial praxis, she is invested in highlighting epistemic potentials within art and literature. Gordon has presented her research at the West Indian Literature Conference.

- All of the women named here are depicted in the mural, and each is represented in the Schomberg Center holdings.Eusebia Cosme is portrayed twice. The second of the two images has been painted over with the yellow of the background.

- Firelei Báez: Joy Out of Fire, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, May 1–November 24, 2018,https://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/firelei-baez-joy-out-fire.

- Alice Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” (1974), in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983), pp. 231–43.

- Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” p. 242.

- Although twelve women are named, there are two depictions of Eusebia Cosme as well as a depiction of Oshun at the center of the mural.

- Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009), p. 32.

- Judith Gleason, Oya: In Praise of an African Goddess (New York: HarperCollins,1992), p. 1.

- Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” p. 232.

- Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” p. 232.

- Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” p. 233.

- Murrell, Afro-Caribbean Religions, p. 41.