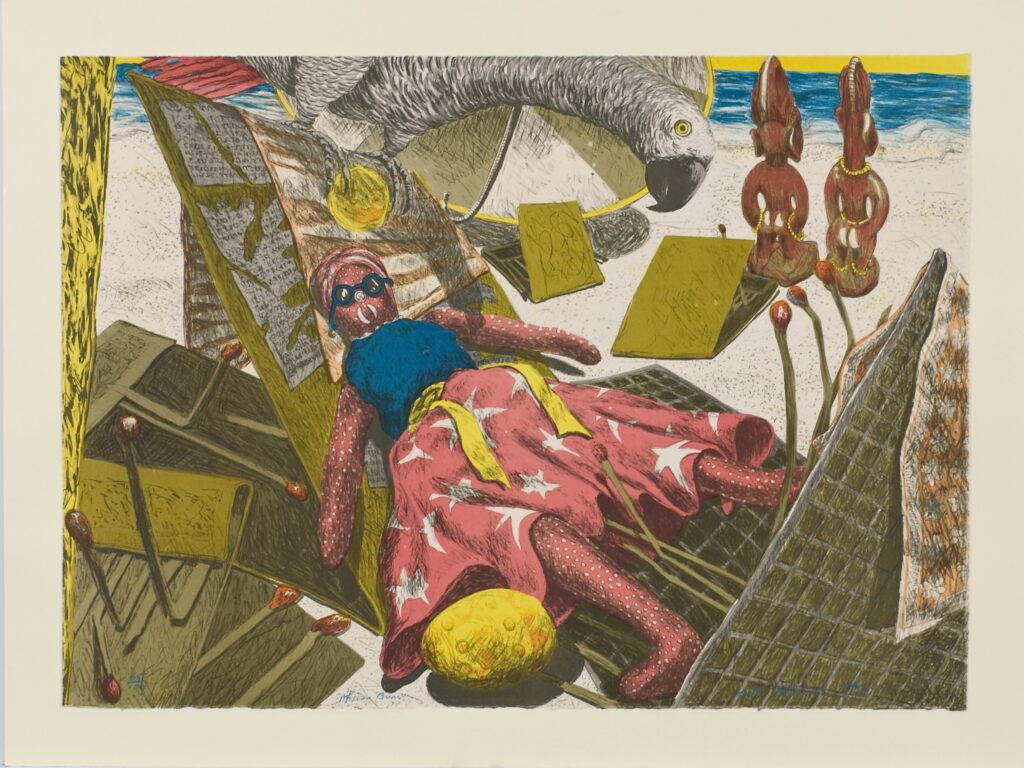

Keith Morrison. African Burns, 1993. Print-offset lithograph. The University of Texas at Austin, gift of Dr. Judith Bettelheim to the Collection of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies. Photo: Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. © Keith Morrison

Bahamian art historian Erica Moiah James begins her dissertation, completed in 2008, with a discussion of Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan (b. 1960, Padua, Italy) and curator Jens Hoffmann’s Sixth Caribbean Biennial (1999).1 The strange project was just the kind of farce presented as institutional critique (or the other way around, depending on who you ask) that Cattelan has come to be known for. The “biennial” had all the hallmarks of the international exhibitions that have mushroomed across the globe over the last few decades—a roster of internationally known artists, press releases, and reviews in major art publications (Frieze managed to spell “Caribbean” wrong in the subtitle of their review, where it remains “Carribean” to this day), as well as institutional sponsorship, etc. 2 The difference is that there was no artwork. The ten participating artists were on “a vacation from art.” Though, as Ann Magnusson wrote for artnet (to the tune of the Gilligan’s Island theme song), “The press release promised . . . ‘Each day, the artists will explain a work of theirs to the most diverse local audiences’ (the maids), ‘often unaware of the international art world trends.’”3

It’s all pretty cringeworthy now, but twenty years ago, it was perfectly acceptable to publish the idea that Caribbean audiences were made up of maids and that the only thing an artist could do in the Caribbean is vacation, or wait out a hurricane. As James points out, all this was possible regardless of the fact that by the time of Cattelan and Hoffmann’s “biennial,” the Caribbean had produced multiple biennials in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic, and Caribbean artists like Cuban Belkis Ayón (b. 1967, Havana; d. 1999, Havana) and Bahamian Janine Antoni (b. 1964, Freeport) had garnered global acclaim. James proposes that it is necessary to “re-world” the world of the Caribbean, to make a distinction between the inner Caribbean, that is, the Caribbean experienced by those who live and work in the region, and the brochure Caribbean, a mythical place and mere backdrop that functions not as a site of intellectual activity, but rather as an escape from intellect.

I begin with this strange incident, not only to point out how recently the “global art world” has begun to think seriously about the Caribbean, but also to highlight a problem of definition that seems to stalk Caribbean studies, regardless of discipline. In fact, among Caribbeanists, it’s a running joke that any text on the Caribbean begins with a map and a couple pages of text lamenting the difficulty of defining the Caribbean. I think these two things are connected. It’s not that Caribbean art hasn’t been collected or thought about, it’s just that it hasn’t always been acknowledged as such. To put it in James’s terms, the Caribbean that Cattelan and Hoffmann projected had no profile in the “global art world,” but many of the other so-called Caribbeans did.

Artists like Nari Ward (b. 1963, St. Andrews, Jamaica; lives in New York), Simone Leigh (b. 1967, Chicago), and Lorna Simpson (b. 1960, New York) are not ordinarily discussed as Caribbean artists, and yet all three are children of Jamaicans who moved to the United States—a very Caribbean story. Wifredo Lam (b. 1902, Sagua La Grande, Cuba; d. 1982, Paris) is a well-known modernist, Hector Hippolyte (b. 1894, Saint-Marc, Haiti; d. 1948, Port-au-Prince, Haiti) is celebrated in naïve art circles, and Jean-Michel Basquiat (b. 1960, Brooklyn, New York; d. 1988, New York) is known as an African-American artist, but with a shift in perspective, all three could be discussed as Caribbean artists. It’s not just artists either. The late Kynaston McShine (b. 1935, Port-of-Spain; d. 2018, New York), who curated the celebrated MoMA exhibition Information (1970), was born and raised in Trinidad and Tobago. Going further back, the collection that launched the British Museum, Sir Hans Sloane’s collection of “800 plant specimens, as well as animals and curiosities” was drawn from the Caribbean, where in the late 17th century, Sloan worked as the physician of a colonial administrator.4 These artists and this curator and collector have produced wildly different work, and they hail from wildly different places (and times), all of which are very much Caribbean. This diversity of Caribbean experience and output means that to speak of the region is often either uncomfortably reductive or unhelpfully broad. If a collection claims to be focused on Caribbean art, one must often ask, “Which Caribbean?” The English or Spanish or French or Dutch-speaking Caribbean? The Afro- or Indo- or Chinese Caribbean? The Caribbean diaspora? Precolonial Caribbean? Post-Internet Caribbean? Quite often, when the Caribbean is invoked, we are not dealing with the whole Caribbean, but rather one of these far more specific categories.

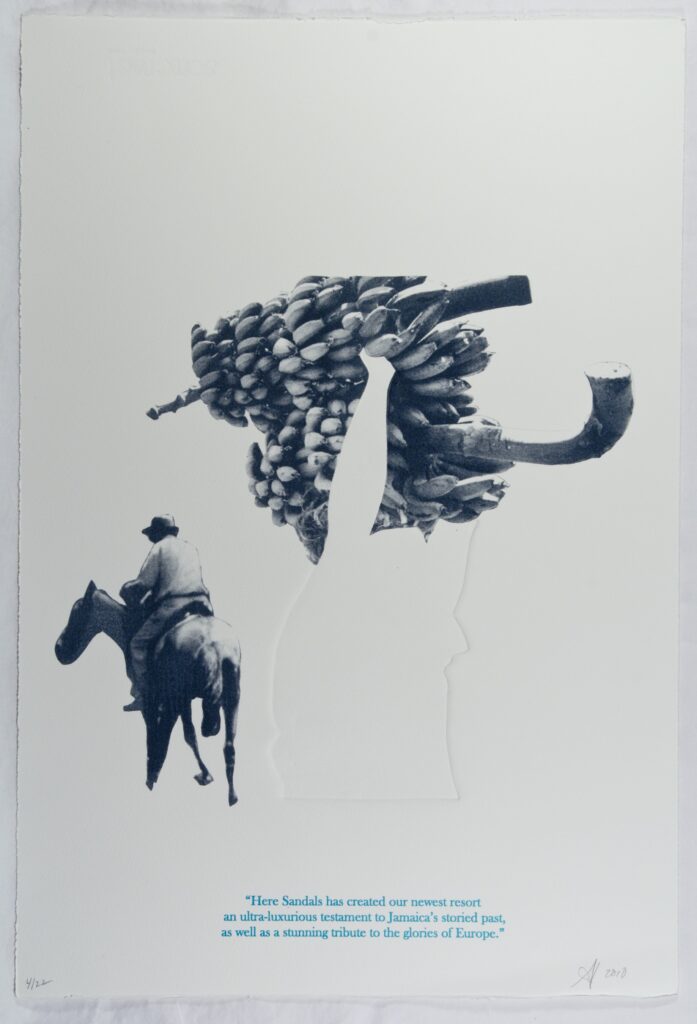

Andrea Chung. Here Sandals has created our newest resort / an ultra-luxurious testament to Jamaica’s storied past, / as well as a stunning tribute to the glories of Europe, 2011. Print-offset lithograph. The University of Texas at Austin, Brandywine Art Prints, Shared Collection of Black Studies and Benson Latin American Collection. Photo: Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. © Andrea Chung

For this reason, I often find that the most interesting Caribbean collections do not try to define the region—not as a list of characteristics anyway. The most interesting Caribbean collections are those that end up heavily inflected by the Caribbean, even as the ostensible focus is elsewhere. They tap into the very thing that makes the Caribbean difficult to define—its multivalence. These collections allow a Caribbean to emerge that is always relational, and if there’s any quintessential Caribbean characteristic, that is it. The region is not so much defined by a single ethnic group or history as by a set of dynamics or relationships that link the new and old worlds, east and west, colonial and postcolonial, black and white, indigenous and migrant, and various other binaries whose neat bifurcations end up muddied and undermined in the Caribbean context. This insight informs the work of influential Martiniquan thinker Édouard Glissant (b. 1928, Sainte-Marie, Martinique; d. 2011, Paris), particularly in Poetics of Relation (1997).5

It was just such a collection that lured me, a writer and curator interested in Caribbean art, to the unlikely site of Central Texas to pursue doctoral studies. The University of Texas at Austin is well-known for two institutional foci: Latin American studies, due in large part to the LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, a partnership of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection and the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies; and Black studies, with the first Black studies program to grant PhDs in the southern United States and the largest faculty cohort of any U.S. Black studies program. Both of these foci have spawned visual arts–specific institutions: The Center for Latin American Visual Studies (CLAVIS) and the Art Galleries in Black Studies (AGBS), which has two spaces: The Christian-Green Gallery and the Idea Lab. Obviously these foci enjoy significant overlap; many Latin Americans and Latinx people are of Black ancestry, and many members of the African diaspora identify as Latinx. There is also institutional overlap since CLAVIS is a part of the Department of Art and Art History, and the chair of African American Studies in the African and African Diaspora Studies Department and founding director of AGBS, Dr. Cherise Smith, is an art historian who remains affiliated with the department.

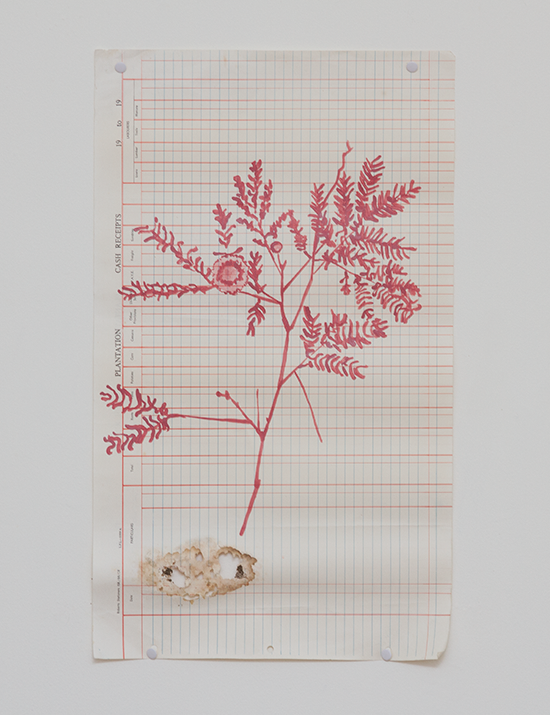

Annalee Davis. Leucaena Leucocephela (River Tamarind) from The Wild Plant Series, 2015 (detail). Latex paint on plantation ledger paper. The University of Texas at Austin, Collection of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies. Photo: Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. © Annalee Davis

A rich Caribbean collection has also emerged in this overlap, which is not surprising. In many ways—culturally, geographically, and even historically—the Caribbean dwells in the overlap between African America and Latin America. As a result, anytime we try to think of Blackness and Latin American-ness at the same time, the Caribbean emerges as a central character. This can be seen in UT Austin’s collections. While the LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections have amassed a significant Caribbean archive and rare books collection, the Black Studies collection has ended up with a rich collection of Caribbean art. The two collections do this without making any claim to Caribbean-ness; the Caribbean simply emerges as central to the institutional Venn diagram that informs their collecting strategies.

In the Black Studies collection, we find work by Jamaican-born artist Keith Morrison (b. 1942, Linstead); California-based artist Andrea Chung (b. 1978, Newark, New Jersey), who was born to Chinese-Jamaican and Trinidadian parents; St. Lucian artist Llewellyn Xavier (b. 1945, Saint Lucia); Bajan artist Annalee Davis (b. 1963, Barbados); and Panamanian artist Arturo Lindsay (b. 1946, Colon). Some of these artists’ works explicitly reference themes that we have come to associate with the Caribbean, like tourism. Morrison’s African Buns (1993) puts today’s sex tourism in conversation with the historic commodification of Black bodies that was the hallmark of the transatlantic slave trade. Chung’s “Here Sandals has created our newest resort and ultra-luxurious testament to Jamaica’s storied past, as well as a stunning tribute to the glories of Europe” (2010) highlights the Jamaican tourism industry’s troubling celebration of the nation’s blood-soaked colonial history, often paralleling resort life with plantation life. Davis’s work picks up a similar thread but takes it in another direction. Davis’s studio is located in St. George on her family’s working dairy farm, which was once a sugar plantation. In works like Leucaena leucocephela (River Tamarind) (2015), Davis mines her own personal and family history, as well as that of Barbados, layering one understanding of the land as a space of commodification and exploitation with a personal engagement with the land as a site of healing. To view and think about the three artists’ work together is to hold various, sometimes contradictory perspectives at once and to contend with the many ways the past remains present.

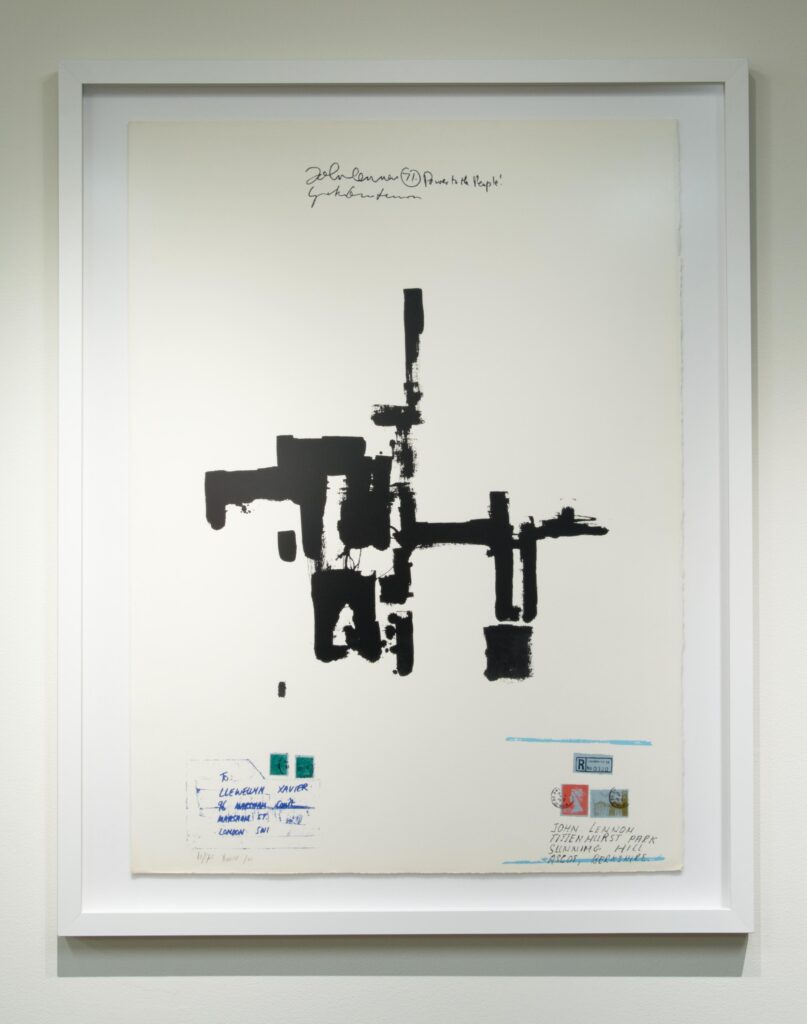

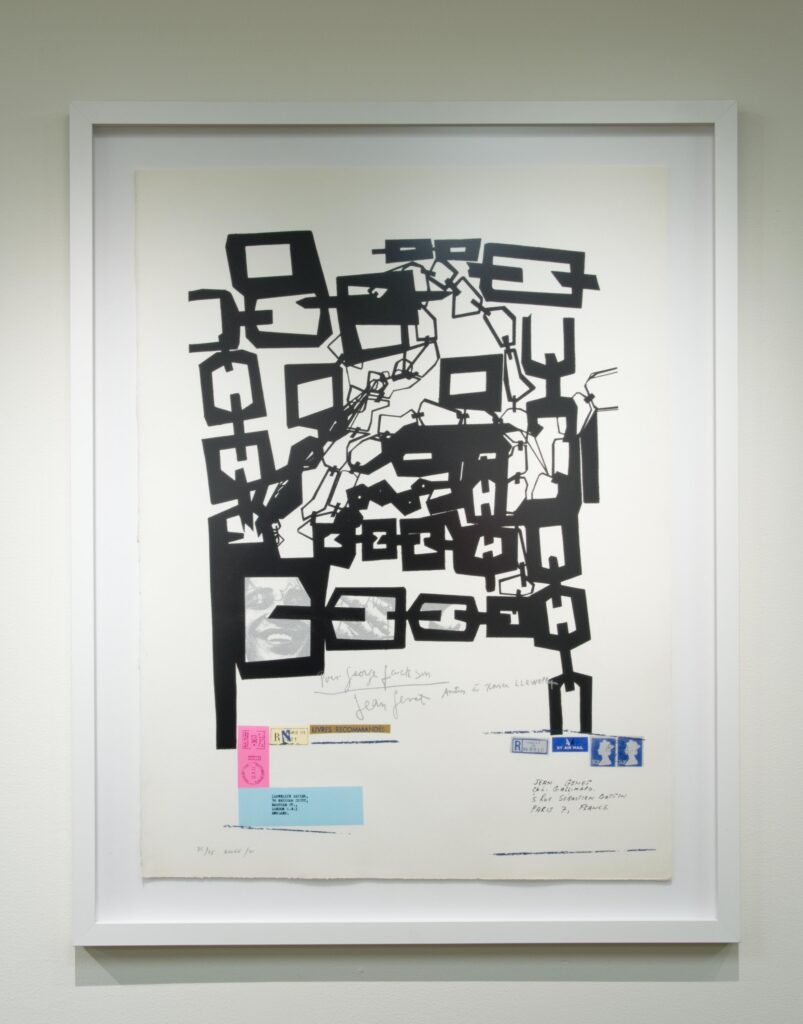

Llewellyn Xavier. Untitled, 1971. Lithograph. The University of Texas at Austin, Collection of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies. © Llewellyn Xavier

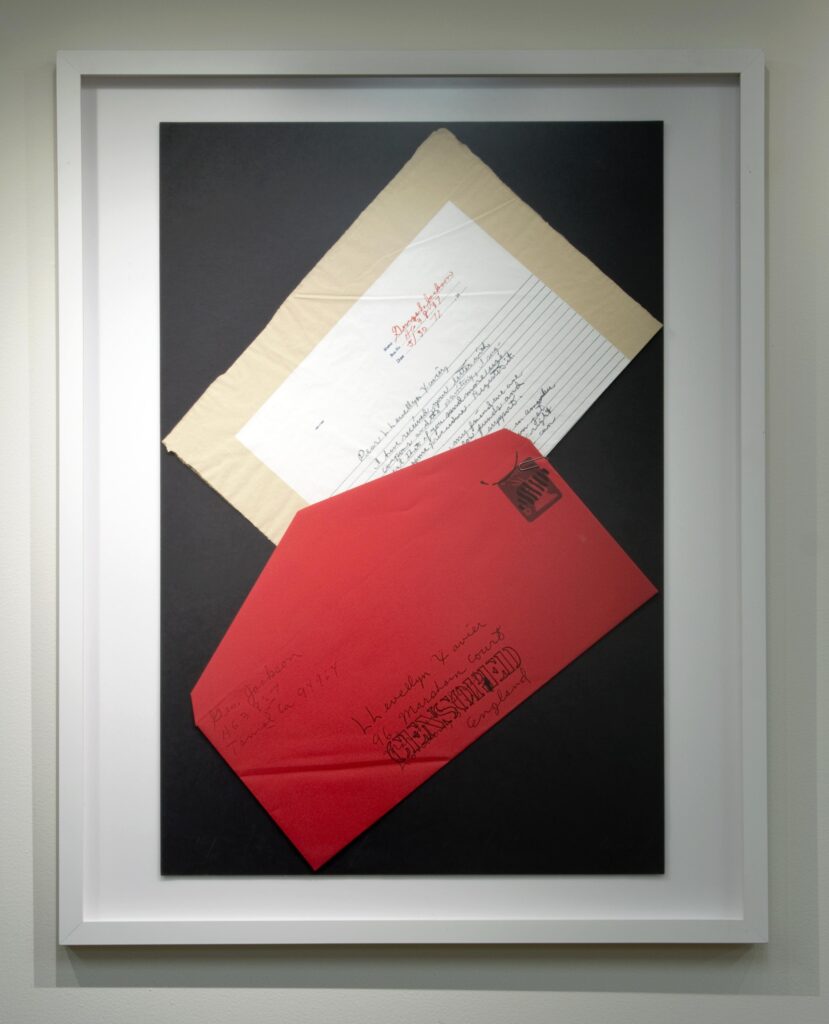

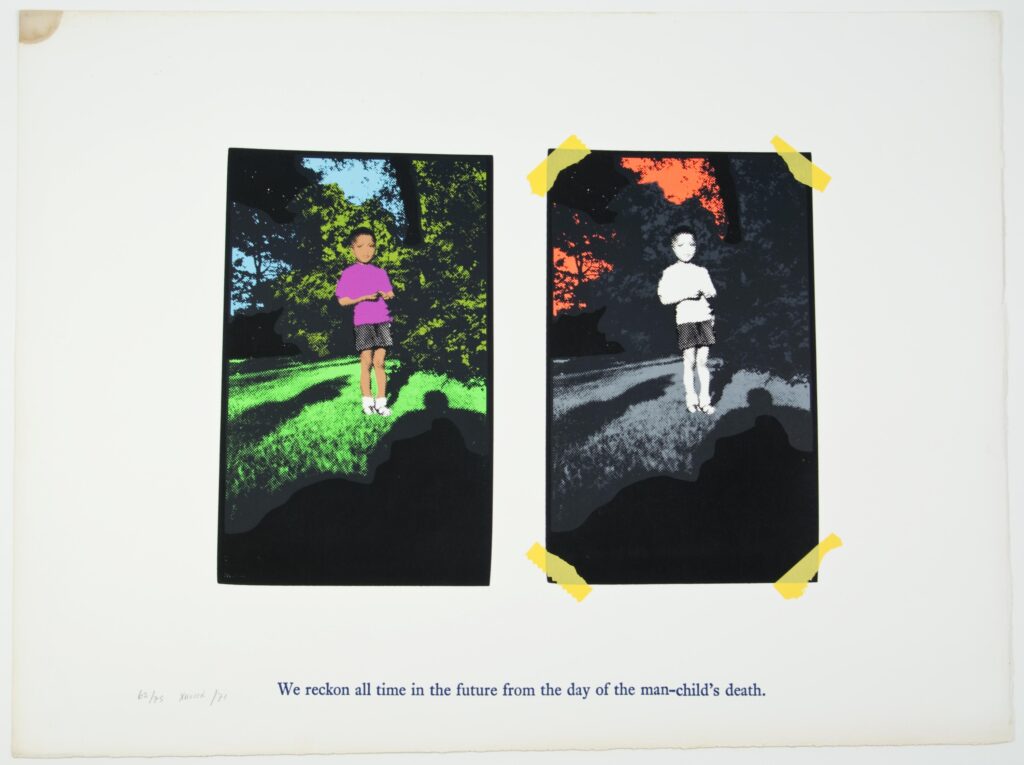

Others lean into the Caribbean’s relational character, the way in which the region is implicated in the politics and culture of apparently far-flung places. The four prints by Llewellyn Xavier in the collection, all titled Untitled (1971), reference the autobiography of imprisoned African American activist George Jackson (b. 1941, Chicago; d. 1971, San Quentin, California). When Xavier read Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson shortly after the book’s publication in 1970,6 he was deeply moved by Jackson’s sophisticated analysis and condemnation of American racism and the then-fledgling prison industrial complex. The book would propel Jackson to fame as an important voice of the Black Power movement, all the more when his younger brother, Jonathan, was killed that same year in a high-profile attempt to free George. George Jackson would also become something of a martyr for the movement when he was shot to death in prison in 1971. Two of the prints in the Black Studies collection were part of a mail art project that Xavier embarked on in tribute to the activist. Xavier produced twelve prints, which he sent to “well-known militants,” including John Lennon and Yoko Ono, James Baldwin, and French writer Jean Genet, who wrote the introduction to Soledad Brother. The works bear the postmarks of their travels, as well as the handwritten comments of their recipients—the signature of Jean Genet in the case of the one in the Black Studies collection. The third print seems to be in memory of Jackson’s slain brother, Jonathan. Two identical photos of a young boy flanked by the shadows of onlooking adults are the basis of the print. In one, bright colors added to the black-and-white print and a quote from Jackson referring to his brother as “the man-child” suggest innocence and potential; in the other, the only color is the sinister red sky, which evokes the younger Jackson’s bloody end. The series was a way for Xavier to make sense of his own experiences of racism while living in England in the 1970s, and it connected him to a global resistance movement.7 The artist would go on to play a part in the British Black Arts movement before returning to St. Lucia later in life. There are few things more Caribbean than the nomadic cosmopolitanism of the works and Xavier’s biography.

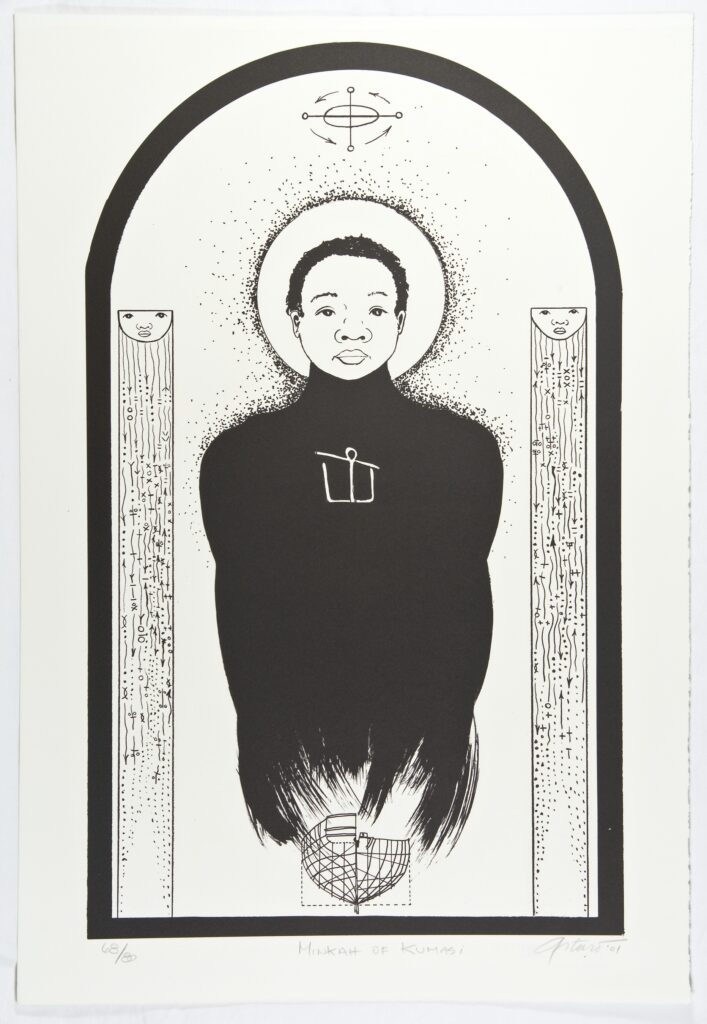

Arturo Lindsay’s Ile of Ile-Ife (2001) pulls us in a different direction, toward the West African origins of communities throughout the Americas. Like much of his work, the print mines Afro-Panamanian culture, which dominates the area he’s from on the Caribbean coast of Panama. This particular print is part of The Children of Middle Passage Series, which conjures children lost in the Middle Passage. Each work depicts an imagined West African child, their appearances “informed by the faces of the children I saw every day in my neighbourhood.”8 The titles deepen that link, using typical African names and connecting them to well-known West African cities. “Ile” is a name meaning “homeland,” and “Ile-Ife” is an ancient Nigerian city. Taken together, Xavier’s and Lindsay’s work indexes the way the Caribbean links Anglo and Latin Americas, as well as old and “new” worlds.

Arturo Lindsay. Ile of Ile Ife, 2001. Print-offset lithograph. The University of Texas at Austin, Brandywine Art Prints, Shared Collection of Black Studies and Benson Latin American Collection. Photo: Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. © Arturo Lindsay

Joyce Christian and Rudolph Green, for whom the Christian-Green Gallery is named, made a substantial donation of artwork to the Black Studies collection in 2016, including several of the works discussed above, and continue to donate work as part of an ongoing commitment. Their collection was conceived as a way to think across the African diaspora from the perspective of their own cultural identities. Their collection includes work by Caribbean artists like Trinidadian Boscoe Holder (b. 1921, Arima; d. 2007, Newtown, Port-of-Spain) and Cuban Belkis Ayón; a substantial collection of Haitian art by the likes of Jacques-Enguerrand Gourgue (b. 1930, Port-au-Prince; d. 1996, Port-au-Prince) and Frantz Zephrin (b. 1968, Cap-Hatien); work by African Americans Michael Ray Charles (b. 1967, Lafayette, Louisiana), Elizabeth Catlett (b. 1915, Washington, D.C.; d. 2012, Cuernavaca, Mexico), Deborah Roberts (b. 1962, Austin, Texas), Sam Gilliam (b. 1933, Tupelo, Mississippi), and the much-overlooked Norman Lewis (b. 1909, New York; d. 1979, New York); studies of Afro-Peruvian life by Peru-based artist Antonio Marquez (b. 1923, Malaga, Spain); and abstraction of Amharic script by Ethiopian painter Wosene Kosrof (b. 1950, Addis Ababa). Green, an African American lawyer who grew up attending segregated schools in Fort Worth, Texas, developed an interest in African diasporic culture beyond the United States after seeing the 1959 Brazilian film Black Orpheus in high school. At first, music was the focus of his exploration, particularly reggae, but as a college student, he took a course with renowned art historian Robert Farris Thompson and visual art began to draw his eye. His marriage to Christian, who hails from Dominica (not to be confused with the Dominican Republic), deepened his engagement with Caribbean culture, in particular. Together, the two have constructed a collection that is reflective of the various iterations of Blackness they have encountered through their personal histories and travels.

The Christian-Green’s most recent donation is a good indication of the potential of their approach to collecting. Jacques-Enguerrand Gourgue’s Cristo de la Libertad (n.d.) takes the figure of Juan Pablo Duarte, one of the “founding fathers” of the Dominican Republic, as an entry point to the entwined histories of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Again, we have a work by a Caribbean artist that functions to complicate the neat divisions that often structure scholarship and collecting.

This tendency to complicate the categories—linguistic, geographic, temporal, etc.— that we often take for granted is to me the promise of collecting Caribbean art. To quote Trinidadian artist Christopher Cozier (b. 1959, Port-of-Spain): “I see the Caribbean as more of a space than a place . . . a space shaped by ways of seeing and thinking derived from our collective historical experiences and a space shaped by wherever Caribbean people find themselves, whether in New York or Rotterdam or off the coast of South or Central America . . . The location is shaped by ways of seeing or communicating . . . by these journeys.”9 With this in mind, we might conclude that it is not necessary for a Caribbean collection to include only art made by people from the Caribbean, but again, we’d get stuck in the conundrum of which Caribbean. Do we include the Caribbean coasts of South America? The diaspora? Do we include artists from elsewhere who are based in the Caribbean—like Peter Doig (b. 1959, Edinburgh, Scotland) and Chris Ofili (b. 1968, Manchester, England)? These kinds of questions might apply to any geographically focused collection, but in a space like the Caribbean, they are especially pressing and fraught. Instead, we might consider collecting from a Caribbean perspective, that is, forming a collection that is conceptually Caribbean in its breadth, and accommodation of tensions and contradictions seems to me a far more compelling prospect.

- Erica M. James, “Re-Worlding a World: Caribbean Art in the Global Imaginary” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2008).

- “Trouble in Paradise: The Sixth International Carribean [sic] Biennale,” Frieze online, March 4, 2000, https://www.frieze.com/article/trouble-paradise.

- Ann Magnuson, “Caribbean Castaway,” artnet, http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/magnuson/magnuson2-24-00.asp.

- “Sir Hans Sloane,” British Museum website, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/sir-hans-sloane.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

- George Jackson, Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (New York: Bantam, 1970).

- Ann Bukantas, “Activism through Art: Llewellyn Xavier’s artworks on George Jackson,” National Museums Liverpool website, https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/activism-through-art-lewellyn-xaviers-artworks-george-jackson.

- Arturo Lindsay, Ibara of Nganya, Artura.org, https://www.artura.org/Detail/title/15495.

- “Interview with Chris Cozier,” Caribbean InTransit, https://caribbeanintransit.com/christopher-cozier/.