The composition of the graduate class has been one of the sustaining pleasures of teaching at the University of Miami. In addition to a diversity of disciplines (the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, Frost School of Music, the Department of English), my Spring 2021 Discourses of Creolization class had meaningful geographic distinctions among the talented cohort who took it: a Cuban student from Havana and a Miami-raised student of Cuban heritage; a student from Kingston, Jamaica, and a Jamaican-heritage student raised in the South Bronx; two Brazilian students—one who made his departmental home in Modern Languages and Literatures and the other who made her home in the English Department. This dynamic mixture of students enabled us to center how much geographic subtleties matter as we approached the assigned readings.

Engaging “creole” and “creolization” as foundational key words in Caribbean studies, the invitation was to think through the various ways these terms and their attending methods circulate across different disciplines and linguistic territories. We juxtaposed definitions that privilege identities formed in the new world to methodologies that grapple with the particularities of historical moments and the shaping relations of power that create conditions of possibilities and impossibilities.

Using Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) as our museum laboratory, the class then applied these insights to Allied with Power: African & African Diaspora Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, which ran at PAMM from November 7, 2020, to February 2, 2022. The following essays exemplify various approaches to analyzing artworks in the exhibition. Bryce Noe sonically activates Lilian Garcia-Roig’s landscape paintings to offer an aural reading of soundscapes erased by urban development; Sade Gordon interprets Firelei Báez’s untitled mural through a diasporic garden of Black foremothers; Gabrielle Jean-Louis unifies the paintings of Naudline Pierre and the drapos of Myrlande Constant through a tradition of Haitian women’s spiritual art and iconography; and Yoán Moreno sees in the work of Tomás Esson and Guido Llinás the exuberant retooling of abstraction that simultaneously moves toward and against identity. Together these essays demonstrate the best of the University of Miami’s Hemispheric Caribbean Studies and the mutually enriching benefits of cross-pollination of museums and academic institutions.

Donette Francis

Director, Center for Global Black Studies

Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Miami

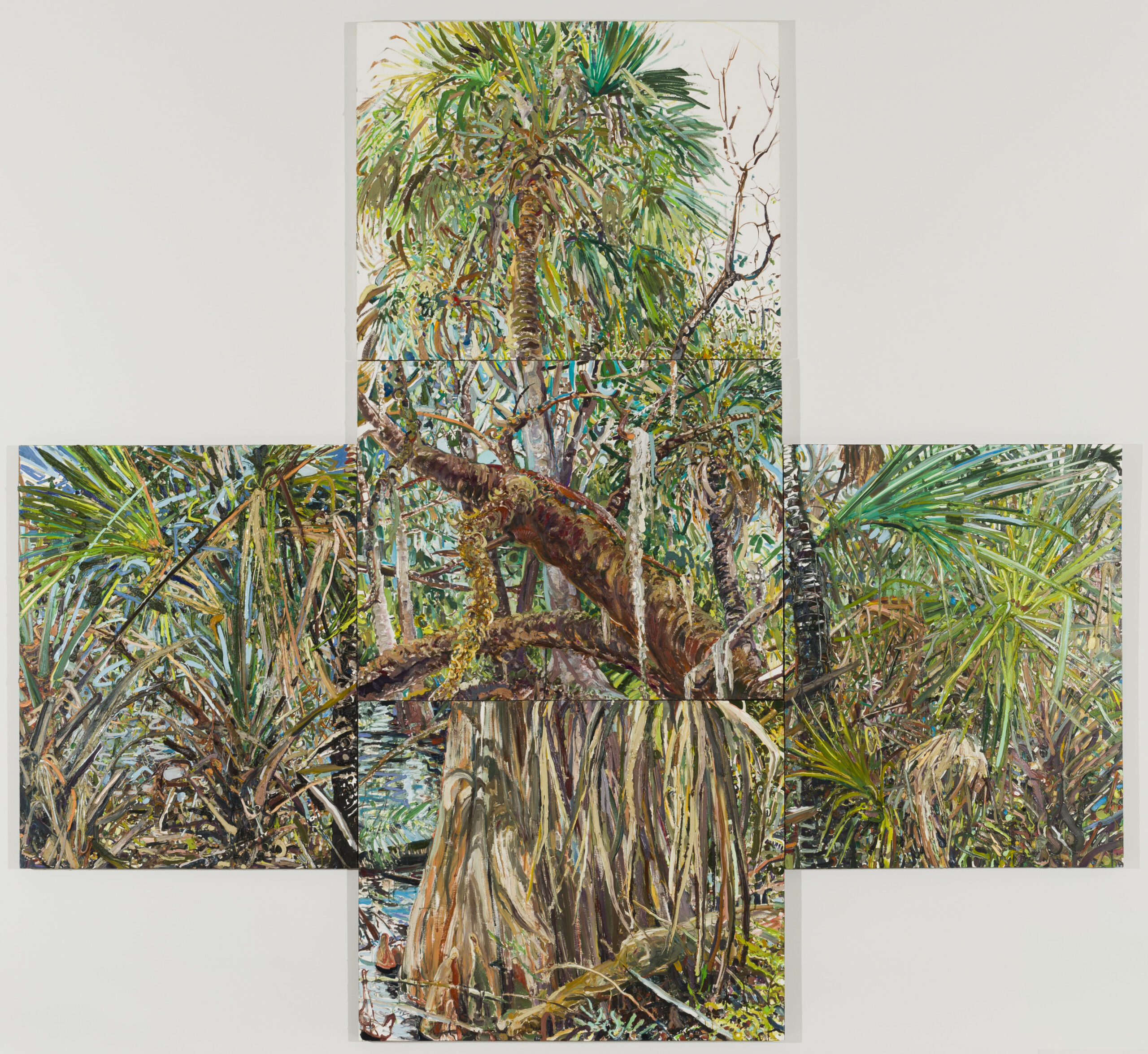

Sound(e)scaping Modernity in Lilian Garcia-Roig’s Hyperbolic Nature: La Florida by Bryce Noe

Comprised of five panels, each depicting separate locations in Florida’s subtropical environment, Lilian Garcia-Roig’s Hyperbolic Nature: La Florida (2012–13) invites the hearing subject to construct and then navigate an imagined natural soundscape. I argue that to imagine Garcia-Roig’s natural soundworld, hearing subjects must silence the sounds of modernity (i.e., sirens, cruise ship horns, and traffic sounds) that permeate PAMM’s interior. Additionally, insofar as modernity in America involves the displacement of indigenous peoples and erasure of their natural landscapes, I suggest that Garcia-Roig’s painting evokes an imagined space for refuge, healing, and belonging beyond modernity.

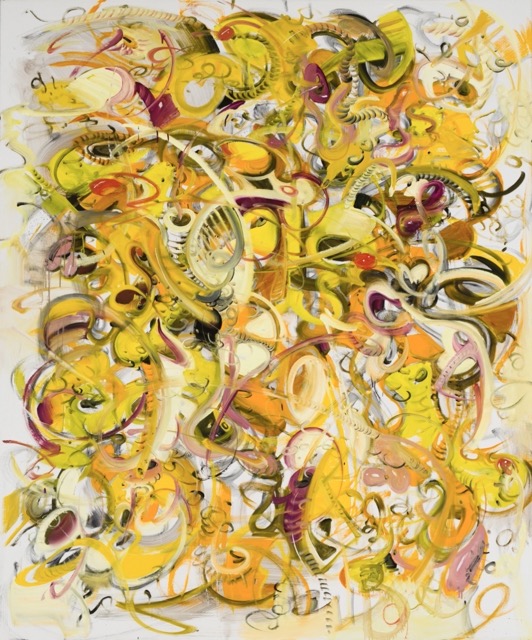

Creole Concrete by Yoán Moreno

This text, written in reference to works by Tomás Esson and Guido Llinás, posits a perspectival and spectral distinction in abstract art on the basis of the latter’s effect on a viewer: the “chaotic figuration” and the “creole concrete.” A chaotic figuration is a work limited by decipherment, a work that pushes the viewer toward a unitary interpretation through the reflex of recognition. A creole concrete is a work endowed with enough ambiguity to resist a single decoding—an identity—instead encouraging mutating and diverging interpretations. This distinction has implications beyond the conceptualization of abstract art.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas

Finding Our Mothers Garden: The Feminine Spirit in Aerial Space by Sade Gordon

Through a close analysis of the untitled mural Firelei Baez created for her 2018 exhibition Out of the Fire, this paper explores the active creative potential of artistic and museum spaces in envisioning connections between Black female creatives, pointing toward a discursive network of community that transcends time, space and Western onto-epistemology. The mural, an inHarlem project presented by the Studio Museum in Harlem in partnership with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, critiques the masculinist ideologies inherent within the Center’s original project of collecting a Black world. Simultaneously it disrupts linearity to realize Alice Walker’s vision of her Mother’s garden.

A Black Feminist Gaze: Haitian Female Artists Reimagining Spiritual Iconography by Gabrielle Jean-Louis

In this essay, Gabrielle Jean-Louis, building on Tina Campts’s A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (2021), foregrounds the disruptive nature of Haitian women artists who challenge the automatic gazes of Whiteness and coloniality by providing an alternative Black feminist gaze. She turns to contemporary Haitian textile artist Myrlande Constant and contemporary Haitian American painter Naudline Pierre, arguing that both participate in a tradition of disrupting patriarchal norms, Eurocentric iconography, and neocolonial classical art forms. She explores two works, in particular, examining how they express a Black feminist sensibility by centering the spiritual lives of Black women and thus further shaping the Black visual art tradition.