In 1931, Cuban designer Clara Porset (b. 1895, Matanzas, Cuba; d. 1981, Mexico City) gave a lecture at El Auditorium de La Habana entitled “La decoración interior contemporánea: Su adaptación al trópico” (Contemporary Interior Design: Its Adaptation to the Tropics) in which she rehearsed some of the era’s most radical ideas on architecture and design. Porset, who had returned to Havana in 1930 after studying in Paris and coming into contact with the ideology of the Bauhaus while traveling througout Europe,1 was advocating for functionalism, for the perfection of forms, the purity of materials, and the “relation of masses, not of superimposed elements.”2 Inspired by the writings of Austrian architect Adolf Loos and early modernist designers like Francis Jourdain and Djo-Bourgeois, Porset attempted, almost for the first time in Cuba, to take on one of modernism’s fundamental problems: the tension between the globalizing and expansive International Style—in line with the development of industrial capitalism—and the local contexts through which it ran.3 In this case, which according to the designer herself went beyond the strictly Cuban context (lo cubano), she analyzed modernism in relationship to the tropics.4

Her lecture, as clever as it was austere, emanated an enthusiasm for architecture understood as a totalizing art, that is, one called upon to integrate form, color, and light as well as to blur the boundaries between craft and art. Porset described architecture as a machine, with furniture, painting, and design as its gears. In place of the term “decoration,” she suggested a vanguardist alternative informed by modernist philosophy: “the art of organizing closed spaces.” Following the precepts of dialogue, harmony, and functionality across diverse structures, she analyzed the coexistence of tropical wisdom accumulated by colonial Cuban architecture (1517–1902) and newer architecture (1940–70), proposing an organic transition that keeps the advantages of the tall post, patio, and foyer of the colonial island house for alleviating excessive heat yet making use of the intensity of the light in the tropics.

In certain cases, Porset recommended excess. For example, to maximize the entrance light and the refreshing tropical sea breezes, she suggested the use of lattices and blinds for windows and terraces in place of closed, uniform panes of glass. In other cases, she recommended austerity—for instance avoiding placing cushions on furniture made of organic wicker, wood, and rattan because when sat upon, they add unnecessary heat to the intrinsic coolness of the tropical materials.5 Both solutions turned out to be fundamental to the subsequent development of modernist architecture and painting in Cuba. Indeed, Cuban architecture in the first half of the 20th century saw the development of a style that some authors have called the “colonial modern.”6

This journey toward the reduction of forms to their most essential shaped the ideological basis of Cuban modernism, not just in architecture but also in painting. From the local Cuban focus (el cubanismo) of the first vanguardia (1927–44) to the universalism of the third (1950–61), Cuban painting morphed into the search for a pure and radical form of abstraction. Contrary to traditional scholarship on the Cuban vanguardia, in which the narrative of formal evolution is predominately male—think Víctor Manuel, Wifredo Lam, Mario Carreño, Sandú Darié , and Luis Martínez Pedro—I argue that this same formal and ideological evolution can be traced equally well through the work of women artists like Amelia Peláez (b. 1896, Yaguajay; d. 1968, Havana) and Loló Soldevilla (b. 1901, Pinar del Río; d. 1971, Havana)—both of whom are represented in the collection of the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM). To be sure, their output not only sits within a wider context of social factors but also dialogues with the output of a wider range of creators, including Clara Porset.

My analysis is inspired by Svetlana Boym’s concept of “the off-modern,”7 which offers a way of understanding modernism that reclaims its radical potentiality, or its potential not just to dream up social utopias or aspire to autonomy, but rather to transform the world. For example, the artistic evolution mentioned in the preceding paragraph would not have been possible without the influence of women’s institutions in Havana like the Lyceum or the Lawn Tennis Club (1929–68), which played important leadership roles within Cuban modernism—and where both Peláez and Soldevilla exhibited their work. It is noteworthy that the Lyceum held the first exhibition in Cuba of abstract art by a woman: Carmen Herrera: Pinturas (Carmen Herrera: Paintings; 1950); that it dedicated space for Eastern European exiles like Sandú Darié to bring their concrete structures to life; that it hosted famous modern architects like Josef Albers and Walter Gropius; and that it mounted one of the most formally and politically innovate exhibitions in 1950s Cuba: Homenaje a Martí: Exposición de plástica cubana contemporánea (Homage to Martí: Exhibition of Contemporary Cuban Art; 1954)—also known as the Antibienal—which energized the abstractionist movement in Cuba in relation to political protests against the II Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte (Second Biennial of Hispanic-American Art) financed by Francoism and the government of Fulgencio Batista (1952-59).

In 1934, at the invitation of Clara Porset, the Lyceum hosted Josef Albers, who gave three lectures that would prove fundamental to the impetus of new ideas about architecture in Cuba. Moreover, Amelia Peláez, Loló Soldevilla, and Carmen Herrera crossed paths at the Lyceum, showing their works in 1934, 1950, and 1950, respectively. In an interview, Herrera describes the importance of the Lyceum in 1930s Havana: “The universities and high schools were closed, but I went to a place called the Lyceum, which was a kind of club that a couple of women had started.”8 To be sure, this “club” had more than “a couple” founders, among them María Josefa de Vidaurreta, Renée Méndez Capote, María Teresa Moré, Margot Baños, and Berta Arocena,9 all of whom had been militant proto-feminists. With the objectives of encouraging the efficient exercise of democracy, subverting the traditional role of women in island society, and including women as essential components in the construction of the modern Cuban and Caribbean subject, the Lyceum sponsored programs related to “Exhibitions, Conferences, Libraries, Music, Social Assistance, Home, Classes, Sports, Propaganda and Advertising, and Social Relations” and worked ceaselessly to open up politics and culture.10 As an institution, it centered women in debates on democracy, modern art, professional development, and political activism against the government of Fulgencio Batista.

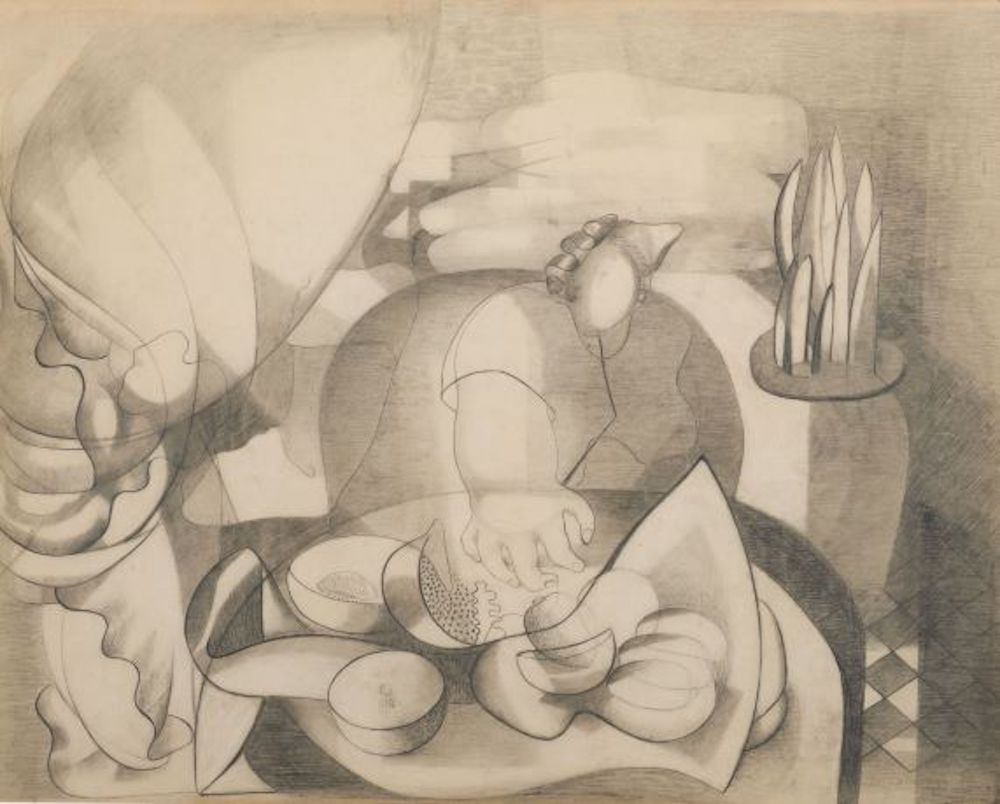

In approaching Amelia Peláez’s work, the viewer can observe not only the beginnings of a proto-feminist consciousness but also the contrast with the output of a subsequent generation of women artists that included Loló Soldevilla. In the painting Autorretrato (Self-portrait; 1935), Peláez depicted the interior of what appears to be a bedroom, incorporating tropical motifs that recur throughout her work: in the foreground, a fruit basket sits atop a table on a mosaic floor recalling the Spanish legacy within Cuban architecture, and in the background, a woman who—sharing the space with what seems to be a decorative plant—reaches a thick arm toward the fruit.11 The painting is bordered by sinuous, abstract motifs that evoke undulating textile forms and give the scene both a dynamism and a certain tropical sensuality.

© Amelia Peláez Foundation

Ingrid Elliott has pointed out the similarities between the female figure in Autorretrato and the seamstress in a series Peláez’s completed in the same period. For Elliott, the image of the seamstress in relation to that of the self-portrait evokes Peláez’s own reflections on the role of women in art and in Cuban society.12 Since the establishment of modern art education in schools like the Bauhaus, women had been segregated, relegated to crafts, or the applied arts, such as weaving, which was considered minor and more feminine. This explains the predominance of women weavers in the history of modern art. Key figures like Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, and Otti Berger, among others, turned textile art into a paragon of design and abstraction. In any case, Peláez not only addressed the role of women in art at the representational level, she also did so in a material way, rebelling against this doit être through her prolific work in painting, and other mediums such as sculpture, murals, and pottery.

Between 1931 and 1934, Peláez studied in Paris under Russian Constructivist Alexandra Exter who, like many early 20th-century women artists, had worked in textile and fashion design. In Paris, Peláez also came into contact with Cubism, and under Exter, she learned about design, color, and composition. Upon her return to Cuba in 1934, she presented the works she had completed in Paris at the Lyceum. Like Porset’s lecture, Peláez’s exhibition was in effect a manifesto renouncing the barriers between craft and art—an idea that was explored in the 2013-14 exhibition Amelia Peláez: The Craft of Modernity, curated by René Morales and Ingrid Elliott at PAMM.13 Contrary to what The Craft of Modernity suggested about understanding Peláez’s work as part of a female ethos of artisanal production, however, the notion of craft did not limit Peláez’s output to an intimate, feminine handicraft. Rather, it broadened her creative horizon, allowing her to reevaluate artisanal practices within the modern tradition. As such, craft can be seen as a precursor of construction and fabrication—as a way of perfecting material and process—not as a minor genre. This explains Peláez’s interest in creating murals for the Havana Hilton (Las frutas cubanas [Cuban Fruit; 1957]) and for Cuban architect Eugenio Batista’s house (1957, now gone), as well as her sketches for a mural for Cuban oil company Esso (never completed), in which she planned to scale up the composition to fit the precepts of modern architecture.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas © Amelia Peláez Foundation

At a formal level, Peláez’s work achieved in painting what Porset sought to accomplish in design: the adaptation of the European avant-garde to the tropics, and a new visual signature of the modern Caribbean subject— one incorporating tropical colors, the wavy shapes of water, and a loose, continuous line that simplified colonial architectural style, bringing the arabesque to minimal representations. In a 1941 article, critic Guy Pérez Cisneros describes how Peláez contributed to her generation’s intellectual obsession with expressing a univeral Cuban ethos or Cubanness (lo cubano) and exorcizing Cuban painting of colonial mimesis.14 “Amelia’s [C]ubism,” writes Pérez Cisneros, “has nothing to do with quintessence: it does not seek the idea of an object, but it does discover, for the first time, many new objects: fruits, fanlights, architectural motifs, pieces of furniture that are creole contributions to the universal, and for that reason it participates in the enrichment of that science of the singular that is art.”15

Peláez’s Cubism advanced not only a subversion of European style, but also a subversion of gender—if one keeps in mind that Cubism was the patrimony of problematic male figures like Pablo Picasso. For Pérez Cisneros—himself a bearer of the era’s prejudice against women—the “decorative and metaphysical” excellence of Peláez’s work is of a “quality that betrays (traiciona) her feminine nature,” distinguishing her as a painter on par with male peers like Víctor Manuel, Mariano Rodríguez, and Fidelio Ponce De León, among others16. In any case, Peláez’s work rebels against these assertions by creating a universe in which form goes hand in hand with proto-feminist perception. Many of her compositions—including her self-portrait—are populated by women who inhabit colonial Cuban interiors (bedrooms) and interact with books (Las hermanas lectoras [The Sister Readers; 1942]) or musical instruments (Las dos hermanas [The Two Sisters; 1946]). Such moments of introspective creativity recall the claim of Virginia Woolf in her famous essay A Room of One’s Own (1929) that the woman artist needs a private space to fully develop.17 Peláez’s vocabulary of images gives the Cuban woman such a space via representation. The arabesques in juxtaposition to the female figures can be read as symbolic of the struggle between the colonial past and the role of women in democracy, a tension that is resolved through the phenomenology of the objects shown. In establishing this dialogue through works like Naturaleza muerta con frutas (Still Life with Fruit; 1935) or Las hermanas (The Sisters; 1943), Peláez’ left no doubt that the sophisticated, abstract, attractive, and complex world she depicted is one perceived by a woman—given the centrality of the female subject. Her work was fundamental in situating the female gaze as a constructive agent of the modern Cuban subject.

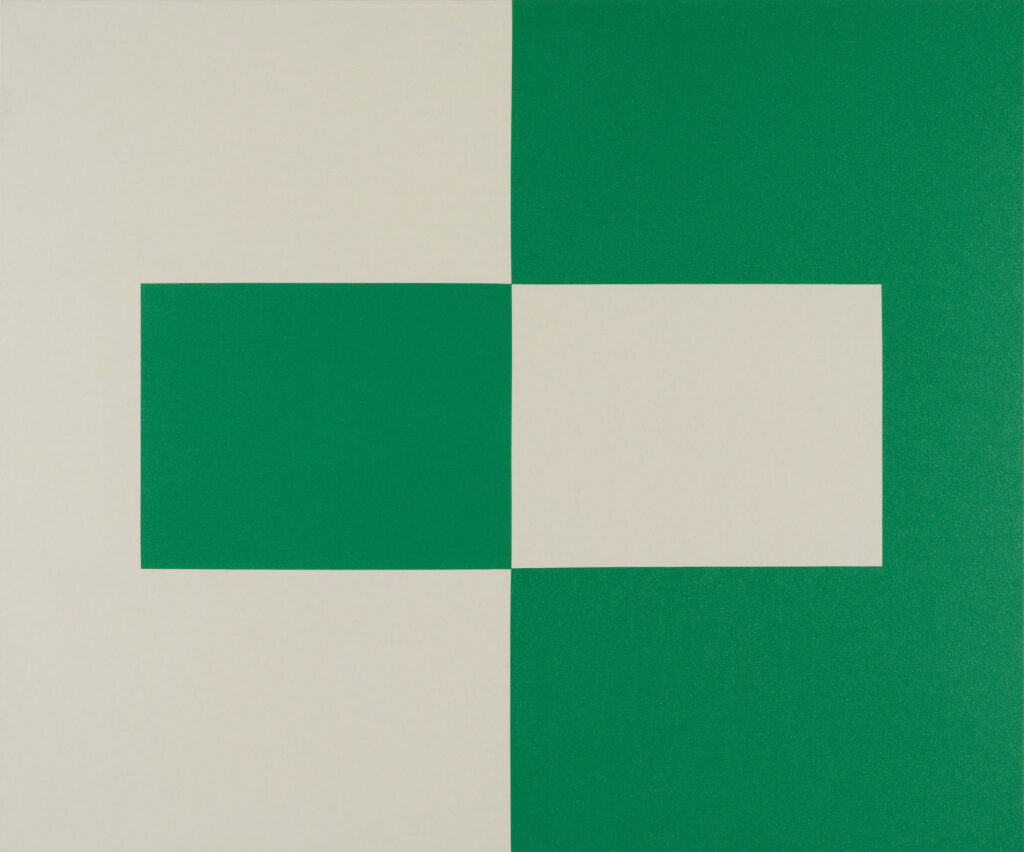

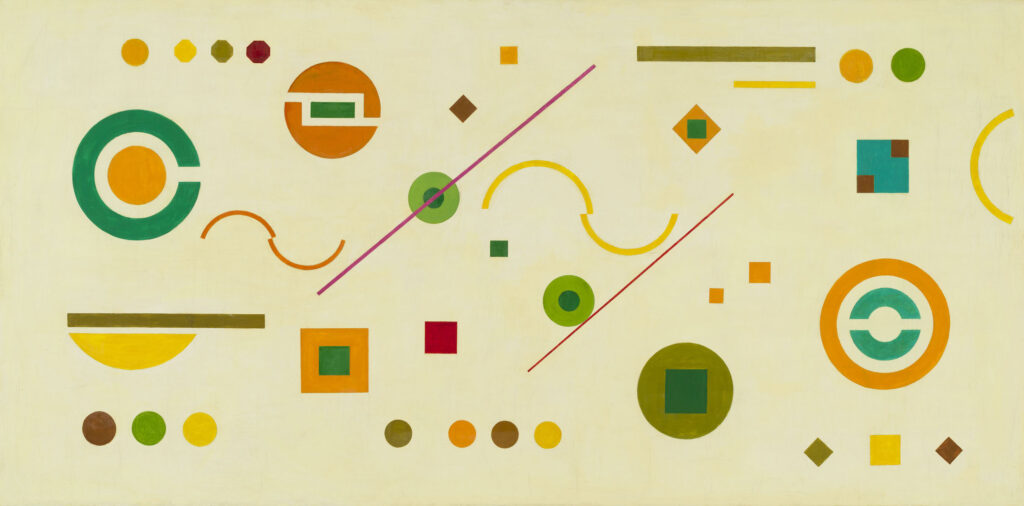

On the other hand, Peláez’s work marked a transition toward more radical spaces—like those associated in the 1950s with Cuban concrete painting, a movement driven by Loló Soldevilla, a woman artist who, alongside other Cuban artists, developed one the most radical formal agendas of the era. In her painting Sin título (Untitled)18 from the series Cartas celestes (Celestial Letters; 1957), Soldevilla brought together circular, square, linear, and curved forms. According to Rafael Díaz Casas’s exhaustive essay on the details of Soldevilla’s life and work, this series was displayed in full for the first time in 1966 in the exhibition Op art, Pop art, la luna y yo at Galería Habana.19 Spanning the fifteen years in which Soldevilla was engaged with abstraction and concretism, this retrospective also highlighted three other important series: Sala en blanco y negro (Black-and-White Room), which consisted of three-dimensional geometric black-and-white reliefs made of wood; Estructuras (Structures), a series of geometric kinetic sculptures, or mobiles with which the spectator was meant to interact, in the manner of Constructivism; and Humoritos, a series of figurative drawings in which the moon represents the artist’s alter ego. Cartas celestes dialogues with the series Constelaciones (1940–41) by Joan Miró, whose work Soldevilla saw for the first time in Paris. For Díaz Casas, this seminal exhibition “was an invitation to travel into mystic adventures, journeys in which light was the finish line but also the vehicle to reach it.”20 Cartas celestes can also be read as an evocation of essential forms within the search for certain correspondences in the ideal language of forms, in the style of Guillaume Baudelaire or Wassily Kandinsky. Indeed, Soldevilla drew much inspiration from Kandisky after seeing his exhibition at Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1953. Even so, and keeping in mind Soldevilla’s status as a “culture worker,” within the vanguardia as she has been labeled by curator Olga Viso, 21 it is likely that her work was motivated by not only formal interests, but also by an interest in transforming reality—in line with the work of the Russian avant-gardists, and visible in paintings by Kazimir Malévich and El Lissitzky, who became crucial references for Soldevilla when she was in Paris. For the Cuban vanguardia artists, forms were not tools for the imitation and embellishment of reality, but rather instruments for changing it. Geometric forms were seen to engage in a secret correspondence with things, preceding any ideology—a relationship that itself became the vanguardist ideology of transformation.

In his essay “The Total Art of Stalinism,” German theoretician Boris Groys argues that the historical Russian avant-gardist approached changing the status quo and culture in a radical way that was later inherited by Stalinism and put into practice by the new Russian avant-gard. According to Groys, “The fundamental thesis of Malevich’s aesthetic is the conviction that the combination of these pure, nonobjective forms ‘subconsciously’ determines both the relationship between the subject and all that is seen and the overall situation of the subject in the world.”22 Political corruption and the automation of capitalist life in the context of the Machine Age had destroyed these pure forms, and thus the artist had to access them as a form of political sublimation and social change. In early twentieth-century Russian society, Groys continues, an inferiority complex with respect to the West predominated, sharing the modernist contradiction of rejecting progress as an element that creates social, geopolitical, and class differences among subjects (access to the new becomes a civilizing symptom), or in other words, looking upon progress as the aggressor. Nonetheless, the contradiction lies in the fact that “at the same time, he [Malevich] considers that the only way to stop progress is, as it were, to outstrip it, finding ahead rather than behind it a point of support or a line of defense offering an effective shield against it.”23

Ideologically, for artists of Soldevilla’s generation, such as the Grupo de los Once24 and Los Diez Pintores Concretos25 or participants in the Antibienal, what was politically and artistically at stake was a “correct” idea of progress, especially given the coexistence of authoritarian governments such as those of Gerardo Machado and Fulgencio Batista. Progress was seen as Paris, New York, the Lyceum, the vanguardia circles of Havana—and all the places that would permit Cubans to imagine a way to improve their society, which was suffering from profound political of both the colonial and other diverse orders. No other figure in Cuban art from this time made the political connotations of the International Style and its “civilizing” sense explicit quite like Soldevilla—perhaps with the exception of curator José Gómez Sicre, who was a champion of pan-Americanist politics in Latin America.26 It is revealing that Soldevilla’s career as an artist began in 1949, after she accepted a position in Paris as a cultural attaché in the Cuban government of democratically elected president Carlos Prío Socarrás. In France, painter Wifredo Lam encouraged Soldevilla to pursue her own artistic ambitions, and so she enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumièrein Montparnasse. In the decade that followed, Soldevilla alternated between exhibiting her paintings and sculptures and laboring tirelessly as a producer, organizer, and cultural promoter, trying to establish a dialogue between Cuba and the international vanguard of art.

In November 1950, the Lyceum held the artist’s first solo exhibition, Loló: Esculturas (Loló: Sculptures). The work Soldevilla presented in this venue was not yet free of figuration, but it nonetheless reflected a debate between “organic” and “abstract” forms.27 That same year, she organized Art Cubain Contemporain at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, a summary exhibition highlighting the most significant Cuban artists of the moment, including herself and Carmen Herrera.

In 1952, Soldevilla set out on her path toward abstraction with the exhibition Loló: Pintura y esculturas, 1951–1952 (Loló: Paintings and Sculptures, 1951–1952).Among the pioneering displays of abstraction in Cuba, it was hosted at the Palacio de los Trabajadores in Havana, the national headquarters of the labor and union movements. Here, Soldevilla’s abstraction found its “corrective”28 role for society as art for the people. In the catalogue accompanying the show, Soldevilla reproduced a fragment of a letter from Wifredo Lam concerning her work: “Like Gauguin, you abandon (an intellectual) position to express yourself within the artist’s irreconcilable freedom.”29 In mounting the exhibition at a union headquarters, Soldevilla converted this “freedom” into productivity and work, into the rejection of any (intellectual) doubt. Moreover, in the work on display, Soldevilla had experimented with different industrial materials, like the polychromatic cement in Relieve (1952) and metal in Hierro-móvil (Iron-mobile; 1952), the latter of which she created in the same period that Sandú Darié was undertaking his iconic series Estructuras transformables (Transformable Sculptures; 1950–60). The spirit of the Cuban art scene of the time had fully absorbed the ideology of the Argentine group Arte Madí and its principal figure Gyula Kôsice, with whom Darié maintained a healthy correspondence. In summarizing what the influential group represented, Kôsice wrote:

“An industrial, mechanistic, and scientific civilization has its correlate in an art that reflects, and most of the time anticipates, a new dimension of the unknown. For the artist, it is not enough to be a survivor of society. . . . It is not about turning architecture into a reigning art, but just the opposite, dissolving all the aesthetic disciplines together in an elevated spirit of leveling and collaboration so that its most active parts, that is, its transformational charge, might have a meaning, a reality, and a communitarian use.”30

Soldevilla’s privileged position in Paris, in addition to her artistic talent and the quality of her work, led to her collaboration with the group CoBrA in 1953 and her friendship with Jean Arp and his wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp; to a solo show at the prestigious Galerie Arnaud, which represented Usonian artist Ellsworth Kelly; and to meeting other Latin American artists based in in Paris, such as Venezuelans Jesús Rafael Soto, and Víctor Varela. In 1957, Soldevilla came into contact with the Venezuelan vanguardia scene in Caracas,31 where she had been invited by Integral, the most important Venezuelan architecture magazine of the period, to put on a solo exhibition. In Caracas, she began to understand space as an integration of color and light, and in questioning the flat background, as an architecture of closed space—with architecture, space, and painting being instruments for the social transformation of her own country.

Upon her return to Cuba that same year, in 1957, with the objective of promoting a vanguardist ideal, Soldevilla and concrete painter Pedro de Oráa, her partner at the time, founded Galería de Arte Color-Luz in the district of Miramar, a multidisciplinary space for lectures, exhibitions, book talks, sculpture, painting, textile, ceramics, and more. The inaugural exhibition, Pintura y escultura cubana (Cuban Painting and Sculpture, 1957), brought together a diverse community of artists including, among others, Amelia Peláez, Sandú Darié, Raúl Martínez, Wifredo Arcay, and Soldevilla herself. The latter, however, already had plans to organize a show of exclusively abstract artwork.32 In November 1959—after Fidel Castro seized power—Los Diez Pintores Concretos (The Ten Concrete Painters) formed, with Soldevilla the only woman member—just as Peláez had been in the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

A look at Soldevilla’s output from this period demonstrates the artist’s formal maturity. Most of her works are dated but otherwise only identified as Sin título (Untitled); to be sure, it made little sense to title the serialized output of an artistic machine. The few titles she did add are descriptive and allude outer space: Paisaje estelar (Starscape; 1959) or the series Cartas celestes. Clara Porset’s tropical adaptation had disappeared by this time because, for her, the tropics had disappeared as a reference, however, in the Cuban context, abstraction and concretism were “a happy discipline of chaos, a ballet on the edge of an abyss.”33 The concrete painting of the times was also an attempt at reducing and controlling the political chaos as well as another tool for so-called social correction and edification. As Groys argues, the Russian abstract avant-garde of the early 20th century was not innocent of the artistic radicalness that Stalinism would later advance; rather, its aspirations to radically change the world were appropriated by the new government to serve an authoritarian and totalitarian purpose.34

In the case of Cuba, abstraction was part of a radical movement that found in the revolutionary triumph of 1959 both its greatest proponent and its own destruction. On January 2, 1959, one day after the victory of the Ejército Rebelde (Castro’s Guerrilla Army) and Batista’s exile, Galería Color-Luz released a manifesto advocating for the defense of “a young and revolutionary art”35 and aligned itself with the 26th of July Movement and its leader, Fidel Castro. From 1960 onward, Soldevilla was a member of the revolutionary militias; she accepted the invitation to teach in the school of architecture at the University of Havana as a professor of non-architectural design; and in 1965, she founded Espacios, an artist group focused on an integrative vision of architecture, art, and design.

Amelia Peláez, Clara Porset, and Loló Soldevilla all participated in the revolutionary government’s official projects for the artistic development of society, including exhibitions dedicated to and in support of the new regime, in pursuit of social transformation, of control over the tropics. Peláez accepted several government commissions and kept her studio in Havana. Porset was involved briefly, from 1959 to 1961, with interior design projects “commanded” by Fidel Castro, such as a furniture commission for the Escuela Militar Camilo Cienfuegos in the east, along with furniture for the Escuela Nacional de Arte. As is par for the course in modern history, the dream of reason became a nightmare after the new government took up the full radicalness of the vanguardist precepts and, by the 1970s, dismissed even the intentions of Clara Porset’s vernacular and artisanal design and Loló Soldevilla’s compositions as obsolete. Nevertheless, these women artists left the door open to the continuity of a republican modernism in the revolutionary period, and to how much of that revolutionary radicalness there had already been during the Cuban Republic (1902-1959).

Peláez’s distracted and introspective subjects, framed by a colonial architecture that has not yet entirely freed them, evolve, in Loló Soldevilla’s work, into abstract forms that argue for an entirely new space for the expression of a “young and revolutionary art.”36 The midway point between these two women could be the work of Clara Porset, which sits between the radical ideas of social transformation and the knowledge of the artisanal and colonial traditions—a nationalist and Identitarian signature. Architecture became a zone of dispute for these three artists because of its capacity to redefine the space in which not only the political dictatorships that lashed Cuba unfolded, but also the patriarchy. This suggested evolution from Peláez to Soldevilla is not just formal, but also political, and it corresponds to the level of agency that women artists had in the Cuban social panorama of the mid-20th century. Peláez’s more contemplative stance is reflected in her studio work after 1959, while Soldevilla became involved in revolutionary militias, university education, and cultural production. All of this warrants a reevaluation of the “innocence” of certain practices carried out by women within artistic modernity, as well as the recognition of their central role in the construction of the social ideology of modern art. In the case of Cuba, that ideology turned into a radical process that devoured, expelled, and segregated its own protagonists. But the work of these three women still stands, not as evidence of interior design, but as a transformative proposition, as spatial and social architecture.

Translated from Spanish by Yoán Moreno.

- Clara Porset studied art at Columbia University in New York City from 1925 to 1928. She traveled to Paris in 1928 to study aesthetics and philosophy at the Sorbonne, in addition to taking courses on art history and architecture at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. Before returning to Cuba, Porset enrolled in the furniture design school founded by the studio of French architect, designer, and illustrator Henri Rapin. While traveling in Europe, she came into contact with the ideas and work of the Bauhaus, which had a profound impact on her subsequent social, theoretical, and formal vision of design.

- “. . . relación de masas, no de elementos superpuestos.” Clara Porset, “La decoración interior contemporánea: Su adaptación al trópico,” in Clara Porset: Diseño y Cultura, ed. Jorge R. Bermúdez (Havana: Letras Cubanas, 2005), p. 2. Translation Yoán Moreno.

- I am not aware of any thinking on Cuban modern interior design before Clara Porset; however, in the early 20th century, Cuban architects began developing modernist ideas about architecture.

- Clara Porset’s work in Mexico is extensively represented in El diseño de Clara Porset: Inventando un México moderno, exh. cat.(Mexico: Turner in association with Museo Franz Mayer, 2006), which includes essays by historian of Mexican design Ana Elena Mallet, designer Oscar Salinas Flores, and architect Alejandro Hernández Gálvez.

- Porset insisted on stripping her furniture of any kind of artifice. She produced spare, functional objects whose main form of expression was derived from the materials constituting them and that combined two or three geometric forms in the interest of ergonomics and tranquility.

- See, for example, Cristina Figueroa Vives, “Nuevo Vedado redimido” (bachelor’s thesis, Facultad de Artes y Letras, Universidad de La Habana, 2006), p. 24. According to Figueroa Vives: “The search that, since the 1920s,

,had become a constant among professionals would find an answer in the trend that architect Eugenio Batista would introduce, and which could be called ‘neocolonial’ modern. This meant a different and deeper approach to the presuppositions of our colonial architecture and its greatest achievements, which has nothing to do with the supposedly historicist ‘neocolonialism’ that many architects tried to impose on the eclectic mansions from the beginning of the century. A few elements of colonial architecture that were taken up again in the architecture of this period, to be later consolidated in the fifties, were the interior patio, interior gallery, arcades or porticoes, large roofs with multiple uses, screened light, stained-glass windows, bay windows, lattices, gates, blinds and bars, among other elements.” Translation Yoán Moreno. - See Svetlana Boym, The Off-Modern (London: International Texts in Critical Media Aesthetics by Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

- Carmen Herrera quoted in Ann Landi, “Shaping Up,” ARTnews 109, no.1 (January 2010):68. This statement is also quoted in Abigail McEwene, introduction to Carmen Herrera in Paris: 1949–1953, exh. brochure(New York: Simon C. Dickinson, 2020), p. 2, https://www.simondickinson.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Carmen-Herrera-in-Paris-Brochure.pdf.

- For more information on the Havana Lyceum and the Lawn Tennis Club, see Whigman Montoya Deler, El Lyceum y el Lawn Tennis Club: Su huella en la cultura cubana, 2nd ed. (Houston: Ediciones Laponia, 2022).

- “. . . Exposiciones, Conferencias, Biblioteca, Música, Asistencia Social, Casa, Clases, Deportes, Propaganda y Publicidad, y Relaciones Sociales.” Whigman Montoya Deler, “Lyceum de La Habana y el Lawn Tennis Club, 93 años después,” Hypermedia Magazine, February 22, 2022, https://hypermediamagazine.com/sociedad/lyceum-habana-lawn-tennis-club/.

- Amelia Peláez. Autorretrato (Self-portrait), 1935. Oil on canvas. 21 1⁄2 x 27 1⁄8 inches. Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of Jorge M. Pérez. Photo: TK

- See Ingrid Elliot, “Crafting Cuban Modernity”, in Amelia Peláez: The Craft of Modernity (Miami:Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2013), 22-38.

- Amelia Peláez: The Craft of Modernity, Pérez Art Museum Miami, December 4, 2013–February 23, 2014, https://www.pamm.org/en/exhibition/amelia-pelaez-the-craft-of-modernity/.

- Guy Pérez Cisneros, “Amelia Peláez o el jardín de Penélope,” in G. P. C.: Evolución de la vanguardia en la crítica de Guy Pérez Cisneros, ed. Beatriz Gago Rodríguez ([Madrid]: Fundación Arte Cubano: Ediciones Vanguardia Cubana, 2015), p. 60.

- “El cubismo de Amelia . . . nada tiene que ver con la quinta esencia: no busca la idea de los objetos, pero sí halla por primera vez muchos nuevos objetos: frutas, lucetas, motivos arquitectónicos, muebles que son un aporte de criollismo a lo universal, y por eso concurre a enriquecer esa ciencia de lo singular que es el arte.” Pérez Cisneros, “Amelia Peláez o el jardín de Penélope,” p. 61. Translation Yoán Moreno..

- Cisneros, “Amelia Peláez o el jardín de Penélope,” p. TK.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (London: Hogarth Press, 1929).

- Untitled, from the series Cartas celestes, ca. 1957. Oil on canvas, 38 x 76 inches, Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, acc. no. 2019.183

- Rafael Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla: Constructing Her Universe,” in Loló Soldevilla: Constructing Her Universe, exh. cat.(Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2019), 9-140. Op art, Pop art, la luna y yo, Galería Habana, Consejo Nacional de Cultura, Havana, Cuba, 1966.

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 57.

- Olga Viso, “Loló Soldevilla: Visionary Artist and Advocate of Cuba’s Mid-Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde,” in Loló Soldevilla, p. 150.

- Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism, p. 15.

- Made up of the artists Guido Llinás, Hugo Consuegra , René Ávila, Antonio Vidal, Fayad Jamis, Tomás Oliva, Agustín Cárdenas Alfonso, José Antonio Díaz Peláez, Francisco Antigua, Viredo Espinosa, and José Ignacio Bermúdez Vázquez, the Grupo de los Once promoted lyrical and geometric abstraction in dissimilar exhibitions and collective cultural events between 1933 and 1955.

- Made up of the artists Pedro de Oraá, Loló Soldevilla, Sandú Darié, Pedro Carmelo Álvarez López, Wifredo Arcay Ochandarena, Salvador Corratgé Ferrera, Luis Darío Martínez Pedro, José María Mijares, Rafael Soriano López, and José Ángel Rosabal Fajardo, the group of the Diez Pintores Concretos was created in 1959 to promote concrete art and the most austere geometric abstraction as a trend in the Cuban art scene of the times.

- Cuban curator, writer, and art critic José Gómez Sicre was director of the Department of Visual Arts of the Pan American Union (today the Organization of American States [OAS]) until 1976. In 1944, he served as consultant for the exhibition Modern Cuban Painters,curated by Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, March 17–May 7, 1944.

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 20.

- “Corrective” in the sense of Marxist-Leninist ideology of art, i.e., art used to improve society by pointing out a defect that must be corrected or punished

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 22.

- “Una civilización industrial, mecanicista y científica, tiene su correlato en un arte que refleja, y las más de las veces preanuncia, una nueva dimensión de lo inédito. El artista no se conforma con ser un sobreviviente de la sociedad. . . . No se trata de convertir la arquitectura en arte monitora, sino por el contrario, disolver en un alto espíritu de nivelación y colaboración todas las disciplinas estéticas, para que las partes más activas de ellas, es decir su carga de transformación, tengan un sentido, una realidad y una utilidad comunitaria.” Gyula Kôsice, cited in Beatriz Gago and Joernis Muñoz, “Más que 10 pintores concretos,” in Beatriz Gago, ed., Más que 10 pintores concretos ([Madrid]: Fundación Arte Cubano, 2020), p. 29. Translation Yoán Moreno

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 45.

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 47.

- “. . . una feliz disciplina en el caos, un ballet al borde de un abismo.” Jorge Mañach, cited in Beatriz Gago, “El espacio cualificado: Mapa para una isla concreta,” in Gago, Más que 10 pintores concretos, p. 29. Translation Yoán Moreno.

- Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism, p. 17.

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 51.

- Díaz Casas, “Loló Soldevilla,” p. 51