Perhaps as we become less human, we will develop empathy for other things, empathy for plants and machines, empathy for the rock and for the minerals carried by the Saharan dust crossing the Atlantic Ocean to rest in the Caribbean islands. Perhaps by becoming less human, we can become more like everything else, and everything else can become more sentient; the planet could become (is becoming?) a sentient cyborg. The hundred-year-old phenomenon of the dehumanization of art could, counterintuitively, lead us down a surprising path of interconnectivity with matter and light, one in which science becomes expressive as art becomes inquisitive. As our societies of control (Deleuze) start to become the societies of the wired brain (Zizek),1 as our technologies evolve from “disciplinary institutions” (Foucault) to individualized control mechanisms (Deleuze) and now to neural interfaces (Zizek, Berardi),2 an opportunity arises, like a glitch in the systems of power, to embrace a process of disidentification (Muñoz) that will make us more empathic, more sentient—that is, more able to sense and make sense of things that before, limited by our humanity, we were not able to sense or make sense of.3 As we become part of the landscape, the landscape awakens. The landscape then becomes aware of things that we, when we were humans, could not see. This might seem like a cyber-utopian desire for the future, but it has been with us for millennia, as certain indigenous cultures constantly remind us.

Guillermo Rodríguez’s work is a conceptual insurgency against the anthropocentrism of the senses. For the beauty of his artworks to be perceived, there is a particular thought process required: one that inevitably makes us abandon the human palette of senses and imagine how unhuman things (plants, machines, minerals, pavement, and so on) sense. There is, without a doubt, both a Romantic and a conceptual aspect (à la Duchamp) to this quest to find other ways of sensing reality; art becomes a laboratory in which science is an ally. Let us take three particularly simple art series by Rodríguez as examples.

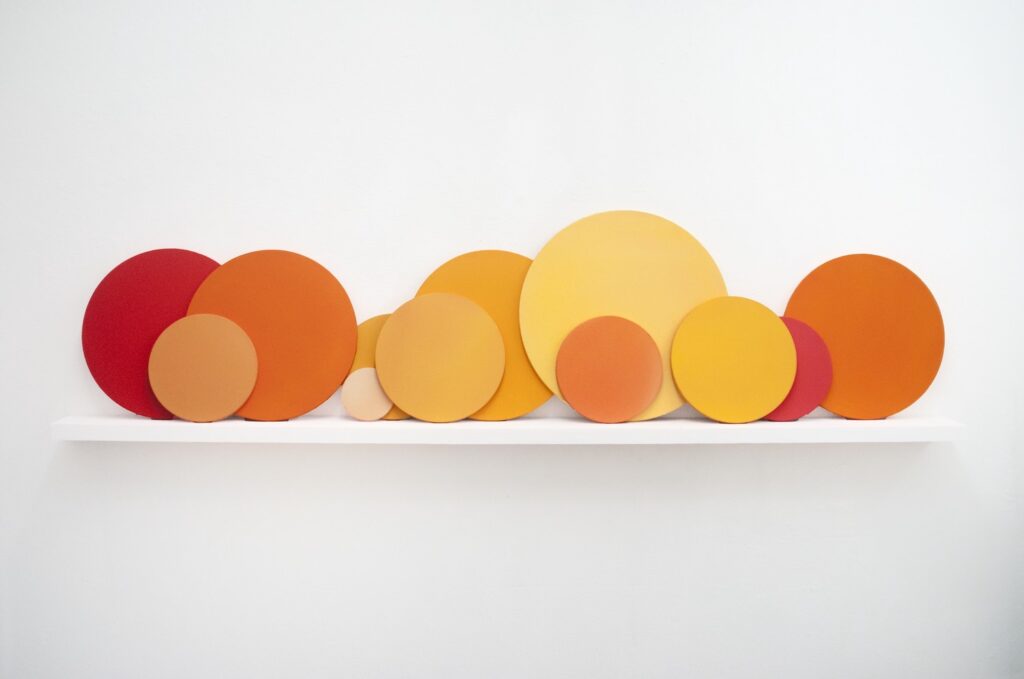

In Balcón/Cianómetro (2012), Rodríguez painted the balcony of the famous Fundación Proa in Buenos Aires in shades of blue like a “cyanometer,” an eighteenth-century instrument used to measure the blueness of the sky, so that visitors to Proa could notice the different daily “blues” of the sky, which we take for granted. Especulaciones (2014–present) and Eyelid Pictures (2014–present) are both series of paintings that intend to represent the color spectrum of orange we see when we face the sun with our eyes closed. And finally, in Haz (2015), which includes pieces from Eyelid Pictures and Especulaciones, Rodríguez builds upon the first photo ever taken of subatomic light behaving as both a particle and a wave. The pieces in Haz then experiment with the materiality of light and our bodily awareness of it.

Photo: Victor Pagán

In Especulaciones, Eyelid Pictures, and Haz, the artist uses science to conceptualize our perception of light and to defamiliarize it in order that we might “see” qualities of light otherwise unexplored in our daily humanity. Science becomes an instrument for exploring sense beyond the human prison of perception, “to catch” the colors that we “lose” all the time.

However, these series are not representative of Rodríguez’s oeuvre. They just give us a first glimpse, a starting point: the memory of a color within closed eyelids. Inspired by José Esteban Muñoz’s study of the artworks of Félix Gonzales-Torres (a definitive precursor of Rodríguez), we would like to describe Guillermo Rodríguez’s artworks as “confounding artifacts of (perceptual) disidentification.”4 Although highly conceptual and experimental with Romantic and sublime tendencies, Rodríguez’s art contains intense political, sci-fi, and even utopian elements that we need to study. As his art avoids, at all costs, human expression and the tendency for identitarian representation, it finds its political call by formal and conceptual means—and this manifests in the confusion it produces, in the “opacity” (Glissant) of understanding (of making sense) that challenges our modern understanding of reality.5 In this sense, Rodríguez’s art aspires to a new epoch of sensorial and philosophical emancipation. Perhaps in the lineage of a Latin Americanized Duchamp, Rodríguez finds in confusion an artistic form to decolonize our senses.

And yet, there is something about Rodríguez’s art that reminds us of the Romantic sublime, of the natural landscapes that in their turbulent otherness and play between light and darkness allegorize our internal turmoil. Beauty tempts this conceptual artist.

Cracking the Romantic Lens in the Caribbean

Yet, Romanticism surrenders itself to a desire to conquer the landscape. This desire is historically intertwined with the modern colonization of the planet by the Logos of the white empires (it is no coincidence that Romanticism emerged during the Industrial Revolution, Frankenstein being the paradigmatic example). This is not what is happening in Guillermo Rodríguez’s art. The Romantic sublime, as we can see in Joseph Mallord William Turner’s famous 1840 painting Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On, turns catastrophe into opportunity and embellishes the destruction of life. The Romantic landscape operates under the logic of conquest; its only beauty resides in its radical otherness, over which human might will triumph. In studying Rodríguez’s art, another landscape emerges—not one that is a radical otherness to be conquered, but rather one that produces a perceptual disidentification in which we now can feel like the landscape in all its immensity, with the human senses and ways of making sense becoming just specks in a much larger spectrum.

In Guillermo Rodríguez’s work, there is a nervous tension between the Romantic beauty of the landscape and the historical catastrophes that determine it. This tension remains unresolved, as if challenging the viewer to historicize what we see as beautiful, shattering the Romantic lens in the Caribbean historical reality.

In 2011 Rodríguez created the series La Isla que se Repite II. It consists of a group of clear acrylic sculptures that, strategically placed in the wet landscape of a Puerto Rican mangrove, refract light. Like massive artificial diamonds, these sculptures of light contrast dramatically with the organic environment of the mangrove, an ecosystem in danger that inevitably reminds us of climate change and the destruction of the seas. The light sculptures in this endangered setting, thus, seem intended to appeal to our sci-fi and apocalyptic imaginings. The title of the piece, which translates as “repeating island,” refers to the fact that the image of the mangrove (a metonymy for the Caribbean) is being refracted, reproduced, or repeated in the glass of the structures. If one looks closely, one can even see the mangrove inside the sculptures, seemingly contained or trapped within their crystal walls. Considering the speed at which mangroves around the world are being destroyed in our warming planet, we cannot help but think of the work allegorically or archivally as a device for historical memory, as the only place in which the mangrove will survive, as its afterlife in extinction. Of course, the title also refers to Antonio Benítez Rojo’s seminal and influential book The Repeating Island (1989), perhaps—along with Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation—the most influential piece of critical theory about Caribbean culture.6 For Benítez Rojo, the Caribbean is the center of the global machine of modernity, a center that is reproducing itself frenetically around the world, multiplying the original formula of capitalism (the plantation system) throughout the world’s colonies, the utmost place for capitalist experimentation. There seems to be a complicity between art and capitalist destruction in Guillermo Rodríguez’s work; a profound critique of art itself (sometimes a condemnation only redeemable by a sense of wonder) appears across his oeuvre.

We believe that this piece, created twelve years ago, contains the seeds for Guillermo Rodríguez’s current series Doppler Landscapes (2023) and Interstellar Topographies (2023), in which he uses technologies for mapping the planet and the galaxy. In his most recent work, Rodríguez is not just mapping, but also emphasizing the means by which we show the planet or the galaxy. Rather than focusing on experiencing the immensity of the cosmos, Rodríguez’s work is centering the materiality of the infrasonic and satellite tools and the “translation” technologies by which we experience (see, hear, touch) that immensity. That is, the emphasis in La Isla que se Repite II is not on the endangered mangrove itself, but instead on the beautiful artifact that captures and reproduces it. Like in Jorge Luis Borges’s famous one-paragraph story “Del rigor en la ciencia” (1946), in which a map of the Empire is so precise that it becomes a replica of it—its precision leading it to become as big as and eventually a substitute for that which it maps—Rodríguez’s art parts from the premise that science and art have problematic and even perverse relations with that which they represent. The representation of the thing threatens the extinction of it.7

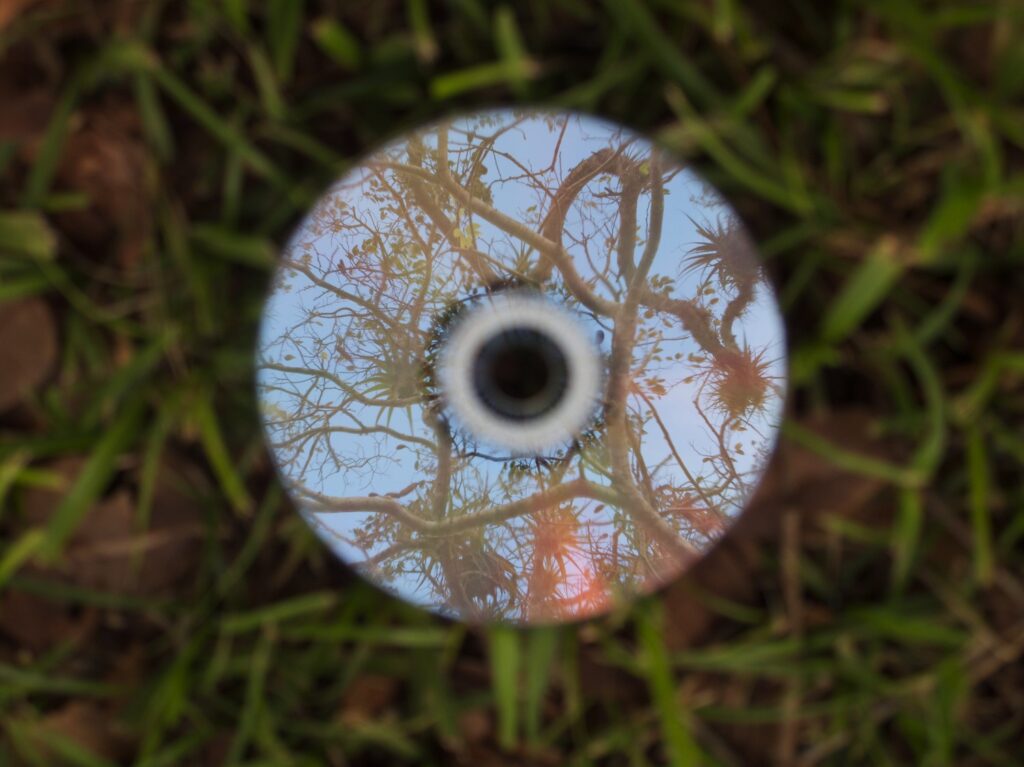

Created at about the same time, Untitled (Data) (2010) seems to double down on the effect of La Isla que se Repite II, though with a less mysterious object in the landscape. Here, a simple CD is photographed on different surfaces composed of grass or dirt. Positioned horizontally, the CD reflects the canopy above the grass or dirt on which it has been placed.

The beautiful crystal artifact of La Isla que se Repite II, an obvious allegory of the sublime of Romantic art, is now replaced by a technology for archiving information that, although equally reflective, substitutes the place of a technology of information for the place of art. Studying these two artworks together, we find a clear critique of Romantic art and its separation of nature from artifice and of art from technology. If Romanticism emerged as a sort of aristocratic critique of modernity and a defense of a “primitive past” against the materialism of modern society and its technologies, then in Rodríguez’s art, we see that this is a false opposition, that the sublimation of nature through art is just a modern technology of colonization, that the sublimation of premodern “nature” through art is just another mechanism of imperial capture, a technology that capitalizes on our fantasies for the beyond.

The traditional alternative to Romanticism is, however, a realist art of denunciation; if Romanticism sublimates nature over which the modern imperial gaze will triumph, realist art aestheticizes the misery that that modern project produces. Yet, a realist art of direct denunciation is not the goal of Rodríguez’s oeuvre. In an incendiary text that Guillermo Rodríguez constructs out of quotes by Colombian writer Luis Ospina but with the very Puerto Rican title “Pornomiseria/Pornomaría,” the artist makes his critique more explicit:

Disaster and misery have become an important topic and thus a commodity easily sold, especially in the North, where misery is the counterpoint of the opulence of consumers.

If misery served independent art as a form of denunciation and analysis, the mercantilist greed that made into the escape valve of the very same system made it possible. This greed for profit does not allow a method to uncover the new premises for the analysis of misery; quite the opposite, it creates demagogic schemes to point that it becomes a genre of what we could call, a miserabilist art or misery-porn.

To consider misery as “other,” given its poetic plasticity or its metaphoric disposition, is to employ it as a source of aesthetic consumption. And whoever accepts to exhibit this instrumentalized and aestheticized misery as another spectacle, where the spectator can wash away their bad conscience, be moved and then sleep well at night, is an accomplice. An accomplice and even more, a participant in the structural conditions that turn human beings into objects, instruments of the colonizing discourse alien to their own condition.8

Both the Romantic art of the sublimation of nature and the premodern or more realist art of political denunciation of the capitalist reality seem to be equally complicit with the colonizing modern project. Here is where Rodríguez’s artistic project becomes unique and quite complex. Avoiding both the sublimation of the premodern landscape and the representation of catastrophe of the realist art or art of denunciation, Rodríguez arrives at a tertiary conceptual alternative: his art shows the interconnection of nature, technology, and catastrophe while it breaks the distance between human subject (be it the artist or the colonizer) and passive object (nature or the colonized). The “human subject” is thus deconstructed into a sensory inclusive landscape. We become part of a sentient landscape in pain. We become part of both the technology and the matter of reality—as in the following artwork made by Rodríguez during this same anti-Romantic period, in which a particular violence against the human form is expressed.

In 2012 Rodríguez presented a playful structure titled Bertopofagia, in which he turned the famous Bertoia stool into a barbeque grill and, at least in the moment recorded in this image, placed it on a Puerto Rican beach. The title obviously refers to the Brazilian antropófago (cannibal) movement.9 Antropofagia was one the earliest vanguard movements to incorporate a decidedly decolonial (avant la lettre) argument in works of art. If we in Brazil or Latin America are seen as cannibals by our colonizers, the Antropofagia movement resignifies that scary cannibal element to defend the way our art consumes European culture and then “digests” it. In Rodríguez’s work, the same is obviously happening. The famous stool designed by Italian American sculptor Harry Bertoia is irreverently transformed into something more useful for us. But something more profound is also happening in this artwork; one can picture the human body being roasted in preparation to be consumed. A process of fire and pain awaits us as we become one with the landscape, as we embrace a becoming beyond human.

Confounding Artifacts of Perceptual Disidentification

In 2022 Guillermo Rodríguez showcased a three-part series at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico titled Mineralia, which consisted of asphalt rocks that, taken from the pavement, look to be stained by the motor oil leaked by the cars that drove over it. These rocks, cleverly painted with nail polish to simulate the rainbows that appear when the sun hits the motor-oil-stained tar in the Caribbean asphalt produced a sensory explosion among Puerto Rican visitors to the museum; we could sense the heat of the Caribbean sun, the smell of wet pavement with its 100 degrees Fahrenheit surface, the smell of rubber, the thickness of the hot air, the tactile friction between car and pavement, and the prism of colors that emerge from this daily sight in a Caribbean urban design that privileges the car over the human.

For the Puerto Rican viewer, the allusion to our catastrophic present—in which austerity measures undemocratically imposed by our Wall Street overlords have deteriorated our entire infrastructure and filled our streets with holes and cracks—is an obvious one. Yet, there was no text, no explanation, no overt denunciation accompanying the work. This art piece, to our understanding, is profoundly political as it can only be conceived after considering the layers of colonial structural design (the dependence on oil and on private cars, the ecological catastrophes of our oil extraction, and the current state of our public institutions under the new fiscal control board). But its focus, rather than an obvious political critique of our reality, lies in the senses. In extracting a piece of our daily landscape and putting it in a place of contemplation, a metonymical magic happens through which our subjectivity suffers a sort of transference. We now perceive from the point of view of the oily asphalt rock. We become part of the crumbling landscape of our neoliberal infrastructure.

More often than not, Guillermo Rodríguez’s art operates in this way. It isolates a part of our daily reality and defamiliarizes it. Only in the act of cutting off a part from the whole, in isolating the specific senses that that particular operation allows, can we perceive beyond our familiar senses. A cognitive process is happening in which we re-ordain our perception of our daily neural paths to uncover the perceptions hidden anywhere, the very effect of our capitalist and colonial condition as something we feel even before we understand it. Such is also the case, more or less, in installations by Rodríguez such as Untitled (Data), Communitas (Wall/Harp) (2013), Lira (2012), Monochord (2012), La Inabilidad de Prever la Praxis (2009–12), and Palimpsesto (2010–present).

All of these artifacts are confounding since they do not make explicit the nature of their representation or allegory. In Disidentifications, his opera prima (2013), art theorist José Esteban Muñoz proposes the concept of disidentification, confronting the identitarian mandate on queer or racially subaltern artists. The art market imposes an identitarian mandate on subaltern artists. Muñoz argues that disidentification (he describes it as “an anti-identitarian identity politics”) could be a formal praxis of freedom and the embodiment of an emancipatory project more revolutionary than the passive acceptance of identitarian art that too easily conforms to imposed representational aspects of the current art market.10 The artist on whom Muñoz bases his polemic hypothesis, Félix Gonzalez-Torres, happens to be an important influence in the work of Guillermo Rodríguez. Gonzalez-Torres, a Latinx, afro-queer artist in New York City in the 1990s, created Minimalist and conceptual artworks that seem, at a superficial representative level, disconnected from his identitarian reality. Muñoz carefully analyzes how Gonzalez-Torres’s context of oppression (the HIV epidemic, white supremacy, and US hatred of Latinx migrants) is ubiquitous throughout the artist’s work, but argues that in order for us to see it, it is necessary that we too make an effort to contextualize his aesthetic intervention.11

Caribbean art and literature, famously baroque and difficult, generates a decolonial illegibility. The reader or viewer cannot passively contemplate. A process of transformation and participation must happen so that we can engage with the artwork—a difficult digestion that questions the very nature of the “consumption” of the artwork. Confusion and illegibility (“opacity” is the term Glissant uses)12 thus become necessary anti-colonial tactics. What you do not “understand” moves you to question your subjectivity (“why do you not understand?” or even, “why do you have this need to understand”). That is, the Caribbean artwork, in its resistance to conforming to the stereotypes that determine your understanding of these subaltern cultures, does not only challenge the mainstream identifications of a particular subaltern culture, it also creates a disidentificatory process for the viewer, a radical questioning of our own passive identities. The analytical confusion that Guillermo Rodríguez’s artifacts create within the viewer follows this neo-baroque Caribbean tradition of illegibility.

Here it is worth highlighting one more art piece, one from 2020 that we are theorizing as a “confounding artifact of (perceptual) disidentification.” And what makes this particular work special, at least in our interpretation, is its utopian aspect. It is a green hose knot suspended in an impossible position—in the form of an atomic particle, or a galaxy, or a mandala.

The title of the work, Aguas aéreas (Aerial Waters), is taken from the title of a book of poems by Argentinean poet Néstor Perlongher.13 This poetry collection is famously psychedelic. It consists of the poet/anthropologist’s experiential investigation in Brazil of the “religion of ayahuasca,” the renown South American hallucinogen used by South American indigenous peoples for millennia. Perlongher’s book also contains an epigraph by sixteenth-century Spanish mystic poet Santa Teresa de Jesus, in which she has a vision of two aerial waters, one covering the skies, made of natural light, and the other a muddled water covering the earth, made of “artificial things.” The allusion to Perlongher, and his to Santa Teresa, puts us in an intertextual knot of references and allusions in which the mystical and the hallucinatory defy our perception of the possible. In seeing the hose knot, we are conceptualizing the water without seeing it, flowing impossibly while flying, “magically” contained and suspended by a capitalist device for the control of nature and the growth of crops (and for washing cars). Confused, lost in its possible interpretations, disidentified in the impossible position of this device made to contain the flow of water, the utopian happens in the mundane. And yet, what kind of utopia is being alluded to here? Is it one of levitation and telekinesis? The sublime that we saw in La Isla que se Repite II remerges in this mundane artifact that alludes to, without showing it, the prime element of water. What sort of perceptual transformation is this confounding artifact of disidentification demanding of the viewer? The answer to that question demands that we activate our utopian imagination. Only then can we become sentient in ways not limited by our humanity. In Aguas aéreas (as we will see later in Interstellar Topographies), Guillermo Rodríguez is translating a cosmic element indifferent to us, to human touch.

Uncreative Dissapropriations or a Proposal against Expressive Art

In literature (the field in which we specialize), there are two contemporary theories or manifestos proposing a sort of documentary literature that cares not for the originality of the creative authorial voice, but rather for how the author reorganizes our historical reality. The first is the concept of “uncreative art” by Kenneth Goldsmith.14 In a decidedly postmodern move, Goldsmith’s poetic praxis consists of appropriating texts from our historical record and formally reconfiguring them, as if there was no more to say, as if language had reached its limit in our historical present of information saturation. The second is the concept of “necrowriting and disappropriation” by Cristina Rivera Garza.15 In a more politicized move, Rivera Garza argues in her theoretical essays and narrative praxis, that every piece of writing and art must also account for the communal conditions that made it possible, including the work of the dead, of those who worked and died so that that piece of writing and art was made possible intellectually and also materially. We are still unsure of where Guillermo Rodriguez’s art lies in relationship to these two sides of the “uncreative” spectrum, between the postmodern and the disappropriated, but we see a definitive dialogue concerning these literary theories in the work of this artist profoundly influenced by literature.

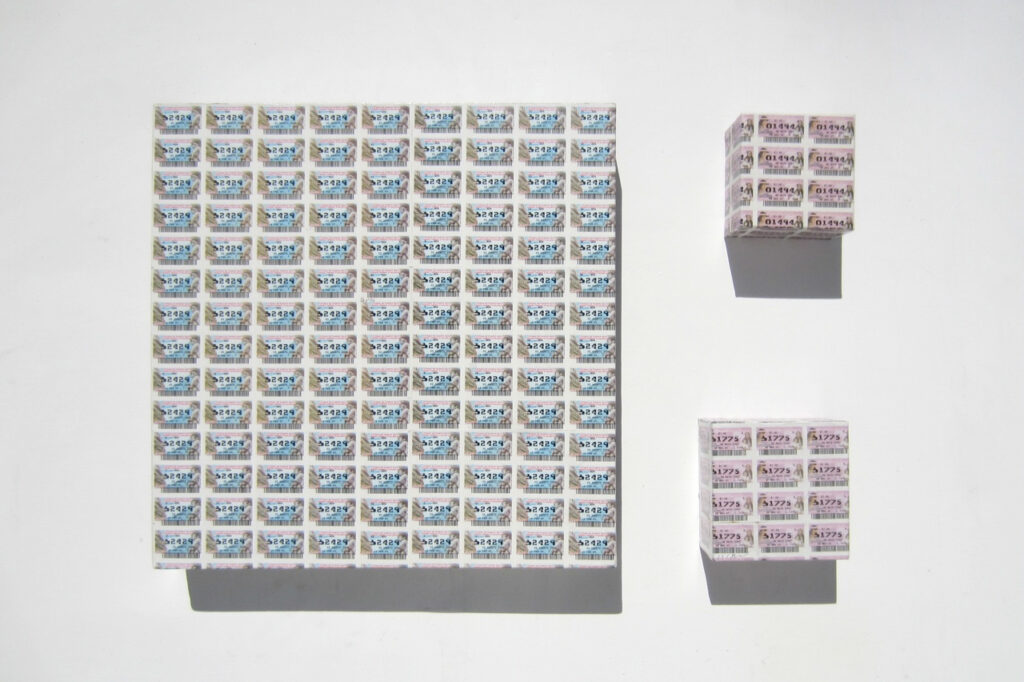

Such is the case of Palimpsesto, a rare piece in Rodríguez oeuvre in that it contains a strong yet hidden autobiographical element. It consists of “unlucky” traditional lottery tickets, arranged in a way reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s now-classic postmodern Campbell’s Soup Cans. Initially, one is tempted to see in these numbers the hopes and dreams of traditional lottery players in Puerto Rico, especially those elderly, rural players who keep engaging in this old form of the game as opposed to the electronic Powerball. But a quick look at Rodríguez’s family history also reveals an homage to his dad, a musician and lifelong supporter of Puerto Rican independence who sold these very same lottery tickets across rural Puerto Rico. As if following Rivera Garza’s argument about necrowriting and disappropriation, Rodríguez is also showing us the work behind his upbringing, the material conditions of possibility that enabled him to become an artist. The title of the piece, Palimpsesto, however, evokes a plurality of communitarian layers beyond the father. These “unlucky lottery numbers” contain layers of human life serialized and contained in an algorithm that manifests materially.

Courtesy of the artist.

The apparently cold and unhuman aspect of Guillermo Rodríguez’s art seems to hide or avoid both expressiveness and autobiographical allusion. However, the expressive aspect of his art is there, as is the human element; one needs only to look closely. Expressivity and humanity hide beneath the layers of nature, technology, and the algorithm.

The Planet as a Sentient Cyborg

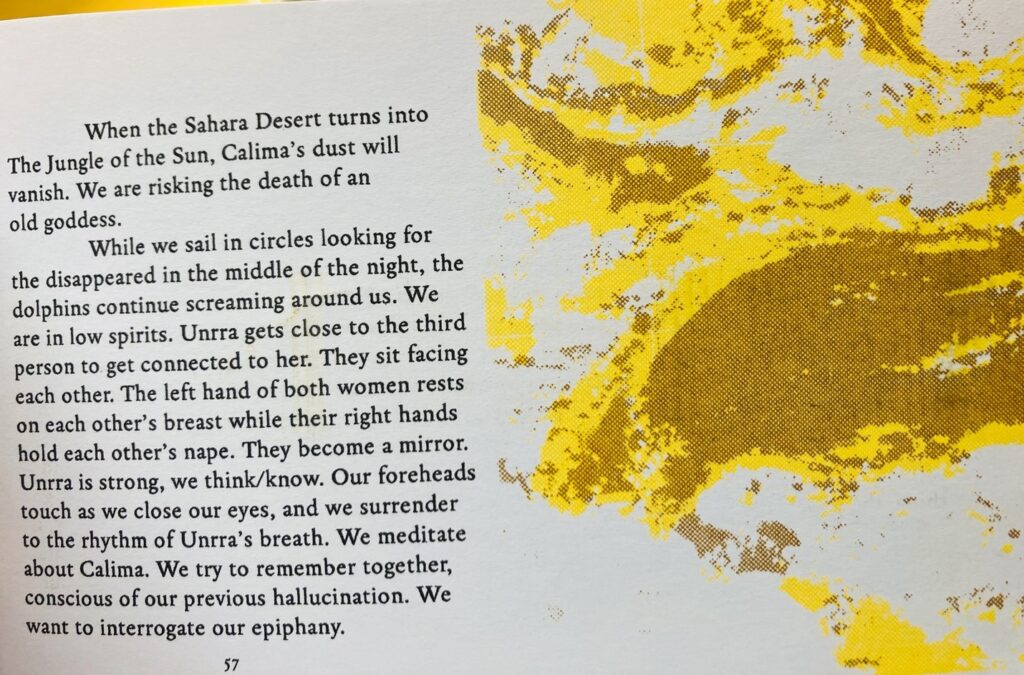

Very much connected to Doppler Landscapes and Interestellar Topographies, one of Rodríguez’s most recent artworks is the animated flip-book collaboration Calima (2023), which he undertook with sci-fi writers, translators, and the artisanal book artists of La Impresora in Puerto Rico.16 Once again, Rodríguez uses and “translates” Doppler infrasonic images, this time of the meteorological phenomenon of the Saharan dust (traditionally called “Calima” by the indigenous peoples of the Canary Islands), which every year crosses from North Africa to the Atlantic and fertilizes the Caribbean and the Amazon, in order to create thirty-eight frames, or pages, that can be animated by being “flipped” with our fingers. The text that accompanies this work is a dystopic fiction set in the future in which humans turn the Sahara Dessert into a jungle by filling it with solar panels. Yet, in this story, the project backfires when the humans realize that the new “Jungle of the Sun” will kill the phenomenon of the Saharan dust/Calima, creating all sorts of new ecological problems. Once again, we have ecological catastrophe, technologies for mapping and sublime artifacts of light. Once again, the viewer must sense (and make sense) of the planet otherwise than human.

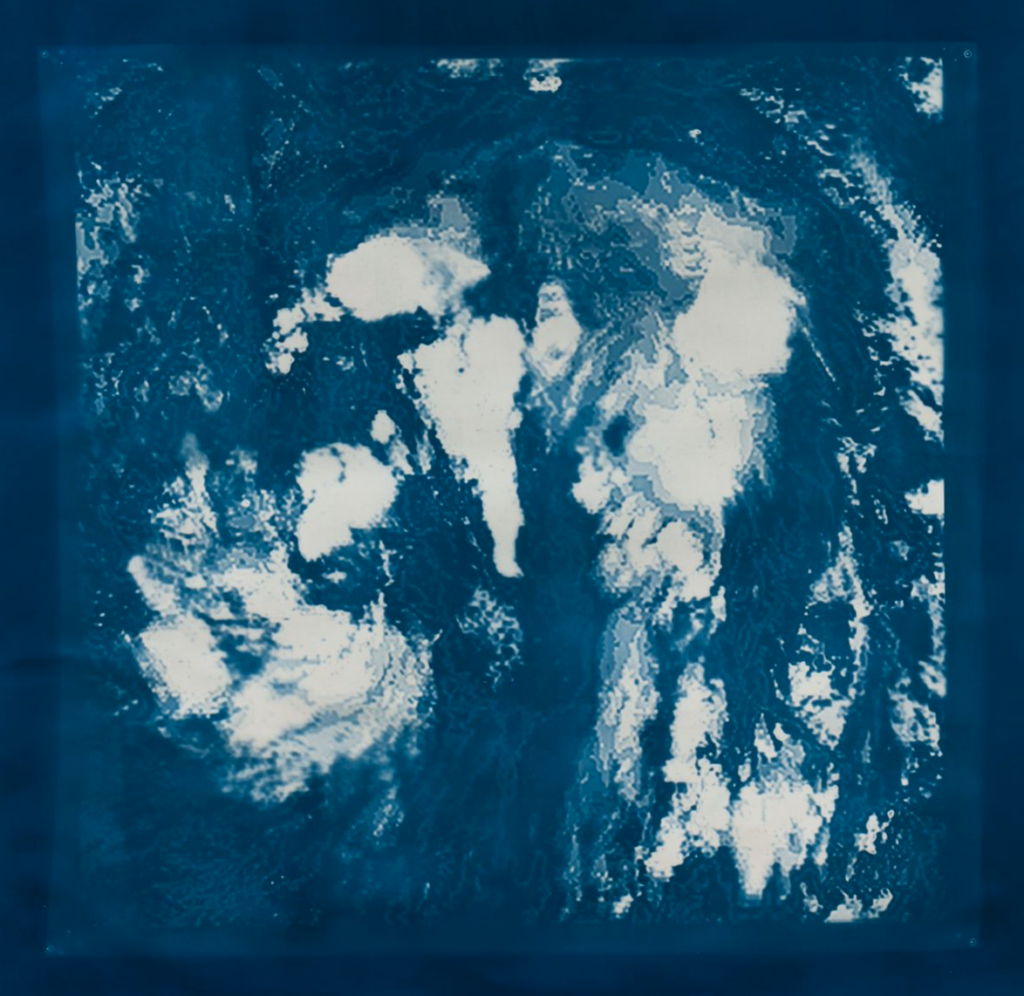

In various interviews, Rodríguez insists on the “infrasonic” aspect of Doppler satellite imagery and on how these satellites “listen” to the atmosphere of the planet and then translate the sounds into images for humans. In Doppler Landscapes, which is divided into three mediums (cerography, cyanotype and neon) and one of his two current art series—Interstellar Topographies being the other—Rodríguez plays with satellite images of the Atlantic Ocean. It is not a coincidence that Rodríguez has chosen this medium. After all, he experienced the catastrophe of Hurricane María in Puerto Rico, which was not a natural catastrophe, but rather a human-made one marking a before and after in the history of the oldest colony in the world. After María, all Puerto Ricans became experts in interpreting Doppler images of the Atlantic, which we see in every morning show. We have all become oracles reading the technological signs of the next catastrophe. When embellishing these Doppler images with artisanal analog technologies of art (cerography, risograph, cyanotypes, and neon), Rodríguez is not just showcasing a view of our planet, but also the way in which Puerto Ricans forecast daily our neoliberal future. After all, as we have said, María was not a “natural” catastrophe but instead the result of our capitalist addiction: a global warming super-powered hurricane hitting an island where the worst neoliberal austerity policies gave priority to profit over life.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas

The atmospheric phenomena in the Atlantic (both hurricanes and the Saharan dust) and our technologies to map it become allusions not just to our historical present of necrocapitalism and coloniality, but also to our historical past. This mapping of the Atlantic also alludes to the trans-Atlantic slave trade that unites Africa and the Caribbean in the foundational sin of primitive accumulation that made modernity possible through slavery. This is the same atmosphere in which Turner painted Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On).17 What is different in Rodríguez art? What is he challenging us to “see,” to “hear”? What are these Doppler-confounding artifacts of perceptual disidentification doing to us? What transformation in the viewer is necessary to actually engage with these artifacts that make scientific data beautiful?

In Interestellar Topographies, which is deeply inspired by the work of blind Puerto Rican astrophysicist Wanda Díaz-Merced, Rodríguez now turns the satellite scope outward into the galaxy. These artifacts translate astronomical data from interstellar phenomena into tactile 3D objects and scale them up so they can be sat upon or otherwise inhabited. At a surface level, these objects allow us to experience cosmic phenomena without privileging our eyesight (this technology by NASA was originally meant for the visually impaired). As in La Isla que se Repite II, in which the mangrove is contained and preserved in an aesthetic artifact, here the galaxy itself is captured by technologies of sensory translation. The eye, as so many art historians have written, is the privileged form in the Western imaginary. At the very first level of interpretation, this white sculpture is aimed at questioning the authority of eyesight over that of our other senses, removing sight and making touch the center.

Yet, something new happens here, something we cannot quite understand, something confounding. Up to this point, the “encountered objects” of our reality, which Rodríguez is playing with in his art, are all determined by our human presence. Capitalism, slavery, climate change, colonialism, and austerity all represent ways in which our human activity has changed our landscape and turned it into this sensual yet catastrophic atmosphere—and all were present in Rodríguez’s work before Interstellar Topgraphies. The problem with this latest artwork is that we humans have not (yet) determined the cosmic landscape we see beyond our planet. What is the might of capitalism compared to the might of a supernova? Something strange and beautiful is happening in the mind of this young Puerto Rican artist. Perhaps a hubris or a cautionary tale; his gaze now turns outward to the unconquered, the uncivilized, the untouched. And, precisely, that “gaze” is being translated into tactile form. Like in Aguas aéreas, utopian in our interpretation, in which the green hose makes the aerial waters touchable, here Rodríguez is daring us to touch the supernova.

Maybe what Interstellar Topographies is doing here is even more radical than touching the supernova; it also implies that the supernova will feel our touch. In an interview with Díaz-Merced, Guillermo Rodríguez refers to Earth as a “sentient cyborg,” and in a way, it is this conversation with Díaz-Merced that inspired the title of our essay. Wanda Díaz-Merced’s research explores what happens when we translate cosmological data into sound and touch, and according to Rodríguez, her research in the field of astrophysics is itself a work of art. In a beautiful and very recent unpublished interview by Díaz-Merced, Guillermo Rodríguez uncharacteristically opens himself up to the astronomer, revealing, still in awe of her research, important clues about his artwork:

Wanda Díaz-Merced: What will the artwork feel?

Guillermo Rodríguez: That’s very interesting. Trying not to humanize the artwork but instead to give it a sense of agency that we recognize in humans: to perceive something and not be aware that this other thing might be perceiving us back is something that ought to be challenged, to make us more empathic. That’s very beautiful. I don’t think I have thought about it before, but at the encounter, the artwork would feel a radical form of empathy. The artwork might get a sense of human perception by reflecting back what we project onto it and that could feel very human somehow, but different. The artwork would feel sensations that are unknown to us.18

Is it true? Will the supernovas of the Milky Way be able to feel our insignificant touch in these 3D-printed sculptures? Will their perception of the infinitesimal “us” make an impression? Is there really a direct action that can connect us to that which we cannot colonize? We don’t know what the art made by Guillermo Rodríguez, still a young artist, will become in the next years or decades. We only know that the horizon of his ambition signals toward touch and trembling. The courageous are not those who resist our unhuman becoming, but rather those who let go. Letting go even though they know that what comes next, might grill them alive. Letting go of the green hose that has taken a life of its own. What kind of surface, matter, light, wave, will we become once everything else becomes sentient?

Postscript

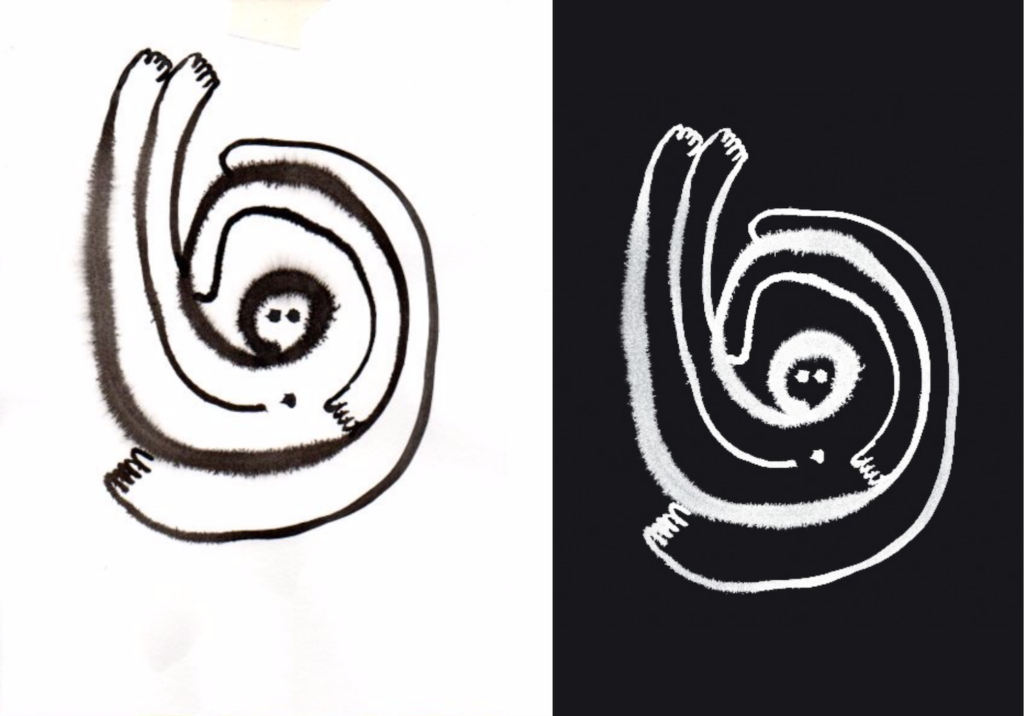

On his website, Guillermo Rodríguez discusses an image by Brazilian artist Flora Rebollo that incorporates an old Taíno rock carving of the traditional form of the hurricane (which, in Taíno art, is always shown as a double spiral) but that also includes a navel in the middle, kind of humanizing the meteorological phenomena from an aerial view, humanizing the biggest fear in Taíno cosmogony.

Dança do umbigo [The Dance of the Navel] simultaneously constructs and destroys. The figure that dances around the navel returns upon its own center in a movement of spirals and solitude. Its form reminds us of Guabanacex, the divinity of the hurricane; the materialization of the worst fear of the indigenous Taíno peoples.

Inside the eye of hurricane, leaves remain unmoved. A double conception surrounds the form of the spiral in this case: on the one side, the introspective and centripetal spiritual journey that tends to order, searching for an internal illumination, and on the other side, the destruction unleashed in centrifugal revolutions that expand themselves toward the external chaos. Like a double helix that simultaneously rotates inward and outward.19

- See Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992): pp. 3–7; and Slavoj Žižek, Hegel in a Wired Brain (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

- See Francisco “Bifo” Berardi, Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility (London: Verso, 2017). See also Michel Foucault, Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison (France: Gallimard, 1975).

- José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

- See Muñoz, Disidentifications. The concept of “confounding artifacts of (perceptual) disidentification” is ours, yet it is very much inspired in Muñoz’s work.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

- Antonio Benítez-Rojo, The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective, trans. James E. Maraniss, 2nd ed. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1996).

- Jorge Luis. Borges, “Del rigor en la ciencia [1946],” in El hacedor (Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1960).

- “Así, el desastre y la miseria se han convertido en tema importante y por lo tanto, en mercancía fácilmente vendible, especialmente en el exterior, donde la miseria es la contrapartida de la opulencia de los consumidores. “Si la miseria le había servido al arte independiente como elemento de denuncia y análisis, el afán mercantilista la convirtió en válvula de escape del sistema mismo que la generó. Este afán de lucro no permite un método que descubra nuevas premisas para el análisis de la miseria sino que, al contrario, crea esquemas demagógicos hasta convertirse en un género que podríamos llamar arte miserabilista o porno-miseria. “Considerar la miseria ajena por su plasticidad poética o su disposición metafórica es de alguna forma emplearla como fuente de goce estético. Y cualquiera que se preste a exhibir la miseria instrumentalizada y estetizada como un espectáculo más, donde el espectador pueda lavar su mala conciencia, conmoverse y tranquilizarse, es cómplice, e incluso partícipe de las condiciones estructurales que convierten al ser humano en objeto, en instrumento de un discurso ajeno a su propia condición.” Guillermo Rodríguez, “Pornomiseria/Pornomaría,”, http://guillermo-rodriguez.com/texts. Emphasis in the original. Translation ours.

- See Oswald de Andrade et al., “Manifesto Antropófago,” Revista de Antropofagia, no. 1 (May 1928): pp. 3 and 7, https://writing.upenn.edu/library/Andrade_Cannibalistic_Manifesto.pdf.

- See the Muñoz, “Performing disidentity: Disidentification as a praxis of freedom,” chapter 7 in Disidentifications, in which he studies the work of Félix Gonzalez-Torres, a definitive influence of Guillermo Rodríguez.

- See Muñoz, “Performing disidentity.”

- See Glissant, Poetics of Relation.

- Néstor Perlongher, Águas aéreas (Guadalajara: Mantis Editores, 2012).

- Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

- Cristina Rivera Garza, The Restless Dead: Necrowriting and Disappropriation, trans. Robin Myers, Critical Mexican Studies (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2020).

- Luis Othoniel Rosa, Calima, trans. Katie Marya and Martina Barinova, with art by Guillermo Rodríguez and book design by Nicole Cecilia Delgado and Amando Hernández (Puerto Rico: La Impresora, 2023).

- For a comprehensive reading on how this painting is profoundly connected to the colonial history of Puerto Rico, see Marta Aponte Alsina, PR3 Aguirre (Puerto Rico: Sopa de Letras, 2018). See also “Luis Othoniel Rosa reseña ‘PR3 Aguirre’ (Dossier Marta Aponte Alsina),” review in el roommate: colectivo de lectores (blog), posted June 14, 2020, https://elroommate.com/2020/06/14/luis-othoniel-rosa-resena-pr3-aguirre-dossier-marta-aponte-alsina/

- Interview between Guillermo Rodríguez and Wanda Díaz-Merced for the inaugural issue of Science in Braille Magazine, DISC: Diversity, Inclusion, Science, and Culture. (Forthcoming). Text provided to author by Guillermo Rodríguez.

- “En la danza del ombligo se construye y se destruye simultáneamente. La figura que danza en torno a su ombligo se vuelve hacia su propio centro en un movimiento espiralado y de solitud. Su forma recuerda a Guabanacex, divinidad del huracán; materialización del peor temor de los indios taínos.” “En el ojo del huracán no se mueve una hoja. Una doble acepción rodea la forma espiral en este caso: por un lado el viaje espiritual introspectivo y centrípeto que tiende al orden buscando la iluminación interior, por el otro la destrucción desatada en revoluciones centrífugas que se expanden hacia el caos exterior. Como una doble hélice que a la vez gira hacia adentro y hacia fuera.” Guillermo Rodríguez, “con Flora Rebollo, La danza del ombligo, 2020,” http://guillermo-rodriguez.com/texts. Translation ours.