Dèyè mòn, gen mòn1

Martinicans have not forgotten him.

No one has described our landscapes more amorously

No one has sung more sincerely of the “charm” of Creole life.

Languor, sweetness—affectations too—Saint Pierre, the

volcano,

“morning like blue satin” “lavender evenings.”

Adorned in flares, in emerald and red sun

Winged djinns and dwarfs peck at bananas

Which are candies heavy with ambrosia

And all the air was heavy with ambrosia under the lasso

Of long and flexuous jungle vines...

That is called Antillean Dawn. And that started a trend.2

…

In her writings of post-colonial theory, Suzanne Césaire pays astute attention to theorizing a diasporic, Pan-Caribbean consciousness that articulated a move away from a specific and distinct Martinican citizen. As one of the founding contributors to the frameworks of négritude, Black modernism, and surrealism, and a co-founder of the Martinican literary and cultural journal, Tropiques, Césaire’s purposely “camouflaged” writings on “political and cultural citizenship in the Caribbean are some of the most forceful articulations of anti-fascism and anti-imperialism in the French Antilles during World War II.”3 Reading her celebrated essays in the collection, The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941-1945), Césaire “reveals a shift in her analytical focus from the legacy of French colonialism in Martinique to the possibilities of a Pan-Caribbean belonging expressed through political practices and artistic creation.”4 It was during her five-month stay in Haiti as a member of a cultural delegation of the French government in 1944 that Césaire claims to have gained “total insight” into the “presence of the Antilles, more than perceptible, from places in which, like Kenscoff, the view over the mountain is unbearably beautiful.”5 As her gaze moves over the mountainous view of Kenscoff, Césaire theorizes “a Caribbean renaissance” that includes “Haiti, Martinique, Puerto Rico and the rest of the Caribbean as interconnected spaces that are also the site of a new Caribbean civilization.”6 While her geographical focus may have been Martinique, what echoes in several of the essays is the desire for an Antillean autonomy and self-actualization that celebrates the complex, multicultural, and multilingual archipelago.7 These generative essays foreshadow the antillanité or tout monde of Édouard Glissant and the créolité of Patrick Chamoiseau, Jean Bernabé and Raphaël Confiant. Correspondingly, Guadeloupe-based, multi-disciplinary artist Ronald Cyrille’s paintings and drawings bring together a visual framework for thinking about a pan-Caribbean consciousness, one based on the similar creative forces and imaginations that compelled Césaire’s reflections on surrealism while imagining the dawn of an interconnected liberated Antilles.

The disturbingly exaggerated and often ghoulish images presented in Cyrille’s paintings do not distract from the beauty of the landscapes or the poignant memories they conjure. Rather, it is in their oddity and peculiarity that we can appreciate a geography borne out of the remnants of enslavement and revolution as visioned through a mythology borne out of survival and resistance. Rather than simply dismiss these works as engulfed in warped perspectives and odd in imagery and narrative, Cyrille interrogates the interplay between creole folklores and language, contes (tales), and childhood memories to navigate the redemptive epistemic possibilities of surrealism and the creative dynamism of magical realism. Engaged in a different type of camouflage, Cyrille notes,

This is where the surrealism comes in, the imagery of the creole, when I put them all together, I am coding my work in a way and if you don’t get it, you might just say ‘oh it is a kind of surrealism.’ This is the escape, because in surrealism, I don’t need to understand everything because it is more than reality, so it is just like a dream. So, in a dream [one] doesn’t look for anything logical. If you look for something logical it is simply to say ‘oh hey that reminds me of…’ so, in the dream, it is not the same, even if it looks familiar.8

In their essay for the traveling exhibition, Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago, which featured work by artists of “Hispanophone, Francophone, Anglophone, Dutch, or Danish origins,”9 curators Tatiana Flores and Michelle Ann Stephens offer an analytical framework for approaching contemporary art of the insular Caribbean “10 This archipelagic approach was introduced in Stephens’s essay, “What Is an Island?: Caribbean Studies and the Contemporary Visual Artist,” in which she writes that using the frame of relationality “would begin to understand the ways the unit of the ‘island,’ as a political and discursive construct, is actually not a part of an archipelago but rather its very antithesis. It is the archipelago—as opposed to the island—that offers a vision of bridged spaces rather than closed territorial boundaries.”11 Interestingly, nearly seventy-five years before Césaire had theorized the Caribbean as an interconnected space rather than a series of discrete islands that sustain distinct yet interrelated artistic productions that incite creative announcements in her “archipelagic politics.” I read Césaire’s “archipelagic politics” and Stephens’ “archipelagic approach” as congruous provocations to recognize in Cyrille’s oeuvre a particular vision generated from an imagination that does not signal specifically Guadeloupe, Martinique, Haiti, or Dominica, but rather, allows for a confluence of creative epistemic approaches whereby archipelagic territories that share histories, languages, and cultures are bound by the littoral connectivity of the Caribbean Sea.12

It is in the capacity of Césaire’s foundational writings about relationality and the camouflage of the “charm” of Creole life that I explore the work of Cyrille, also known as B. Bird. My goal in this essay is to highlight how these selected paintings, drawings, and mixed media collages on paper that capture his tropical surroundings and illustrate his deep and capacious explorations of familial memories, cultural identities, and folktales are animated by linguistic fluidities. By linguistic fluidities, I am suggesting that creole, the language derived from enslaved Africans, European colonizers, and the Kalinago (the original inhabitants of Dominica, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and the Lesser Antilles) has played a pivotal role in animating Cyrille’s foundational images. His use of the colorful verbal and visual interplay of paroles and contes illustrate how these folktales play a prescient role in the symbols and images that populate his canvases and murals. Recurring images such as a two-headed dog-bird, figures with bird-like beaks with big teeth, and tree-like elongated invented figures take center stage as they dwell in flora from chataigne (breadnut), and fruit à pain (breadfruit) trees commonly found in different parts of the Caribbean. Writing about what influences him, Cyrille notes “It is also a personal mythology animated by the image of the dog-bird and an obsessive and symbolic universe where the conventional has no place. Narratives are born with their own codes, their own meaning linked as if spun [by] metaphors.”13 These narratives are nourished by the expressivity of the creole language, its peculiarities and nuances, its radical linguistic possibilities, and what lies in-between these blended veiled words. This Cyrille terms the “‘magico-religious imagination’ of the creole language that allows us to move beyond the conventional and to an ‘elsewhere’”.14

Born to a Dominican mother and a Guadeloupean father in Guadeloupe, Cyrille moved to Dominica at eight months of age where he lived with his grandparents. At the age of nine, he returned to Guadeloupe, where he currently resides. He received a National Arts Diploma in 2009 at the Campus Caribbean Des Arts in Martinique. There he studied with Guadeloupean artists Bruno Pédurand and Henri Tauliaut, and Martinican artists Ernest Breleur and Hervé Beuze. In 2012, he received his master’s degree at Campus Caribbean Des Arts, returning to Guadeloupe that same year to establish his art practice. Known for his paintings, mixed media on paper, and street art murals, his work might be thought of as complex mixtures surrealism and magical realism—but it is not quite that. In fact, Cyrille does not consider himself influenced by surrealist art. He writes, “although my works often escape a Cartesian logic, they want to be the witness of a freedom of gestures, research, and creations. My works are often born from an improvisation and a spontaneity which is intellectualized and refined during the creation.”15 Nonetheless, his works synthesize evocative representations and mesmeric scenes animated by the nostalgic memories of his childhood in the tropical landscapes of Dominica and Guadeloupe. Always interested in experimenting with different mediums and genres, Cyrille describes his practice as follows:

My work is mixed, like me. The choice of medium is based on what I want to express. If I want to express movement, I might use video, because it is easier to express this using video, if I choose painting, that painting has to be dynamic, we have to see the mark of the brush. If I chose drawing, I want the line to have more strength than the color. When I paint, the color has to have strength that it can erase the line … For me, the line is the way to go straight from what I am thinking and my hand. When I draw, it doesn’t have mistakes. The way I process all my work, I never know what I am going to do before I start. The idea comes and I begin a work and it might change halfway through. I don’t always follow the painting. If I make a mistake, it is not a mistake. It is just like life; I have to see what I have to do with it for it to be part of the work. That is why I don’t draw with crayon, [or] with pencil, because every mark has to stay. I draw with pen. Then I can’t erase nothing … the mistake brings me somewhere I didn’t plan to go.16

Cyrille employs a blend of powerful visual languages and thematic explorations. In their bold color palette, his compositions are often saturated with abstract motifs joined by distorted faces, figures, and forms. There are elements of “reality” in the compositions; however, they are often skewed and exaggerated shapes that according to him allows for a certain “passion et liberté.” In that passion and liberty, there is often more than meets the eye. At first glance upon seeing his work, our desire would be to describe his work within the “poetically rich” metaphors of surrealism and radical imaginative possibilities of magical realism, one anchored in the “revolutionary deployment of language.”17 Given a deeper and more penetrating look, however, it is through childhood memories and well-known tales and contes of la sirene, soucouyant, manman dlo, and la diablesse that Cyrille illustrates the intrinsic relationships among humans, the environment, and nature. These relationships that Cyrille figures are as reflective of man’s impacts on the natural world as they are of nature and the environment’s effects on the human. Through this interrelation, he evokes a new form of life in the manner of Césaire, a “plant-human” that occupies picturesque landscapes and narrate stories filled with tense dialogues. We can consider this figure to be an element of the anthropocene.

Posing a rhetorical question, “What is the Martinican?” Césaire replies,

—A plant-human. Like a plant, he abandons himself to the rhythm of universal life. There is not the slightest effort to dominate nature. Mediocre farmer. Perhaps. I am not saying that he makes the plant grow: I am saying that he grows, he lives in a plant-like manner.18

Distorted figures dwell in plants and vegetation common in the Antillean landscape in Cyrille’s works, leaves sprout from the heads of half-human, half-dog figures, while arms and legs form tree limbs stretching towards the sky. One sees the natural world as it is but always with an element of surprise. Red apple-shaped creatures hanging from branches move beyond what we know them to be. It is these “plant-human” figures that materialize in Cyrille’s paintings. They capture his perceptive and aesthetic inventiveness and suggest a symbiotic relationship between man and the land, one that “re-establishes Martinique [and the Caribbean] as a territory animated by a revolutionary potential, rather than [seeing it as] a timeless Eden.”19 Cyrille’s “otherworldliness” is not a direct rendition of an idyllic nature. He is not presenting us with a world that we know, but rather a world that exists in his imagination. He wants us along on that creative journey.

As someone whose artistic practice takes place in a studio as well as the streets of Guadeloupe and other parts of the Caribbean, Cyrille experiments with different mark-making techniques as he employs unconventional colors and exaggerated bodies to indicate human forms that dwell within tropical landscapes. These stylistic elements are exacted through bold strokes that render the images readable and at other times unrecognizable, familiar but slightly out of place, unfamiliar. It is perhaps that illegibility that makes his work so fitting for a postmodern Caribbean body. When speaking about the way he begins a painting, Cyrille says,

I don’t have a sketch book, I come in and begin to paint. I drop the color and from the first drop, try to travel in it and then design the place I can figure in what I drop on the canvas. So, most of the time I start with one color, almost with a dark color, like black. I feel when it is in black, it is fuller. And then now I have to empty it a little bit, unfill it with what I will put on it, my stories.20

It is in the deliberate and strategic compositional elements that we can determine the deep and contextual meanings of his painting. It is in the skillful placement of images that Cyrille creates an aesthetic inventiveness that centers both nature and the figure—one does not suppress either one. The implication is that nature and these imaginary figures do not stand alone; rather, they are implicated and brought together within the frame through boldvibrant hues of oranges, reds, blues, and strategic areas of black. He says, “When I wake up in the morning and see the way the sun hits the trees in the morning, these colors are important to me, and I try to mirror those colors in my paintings. Color is more about impact.”21

For example, in his ongoing series Green Paradise Lost: Freedom (2015), several shades of blue combined to form the perfect sky, while yellow-colored brush strokes draw our eye to the background where a dog-head shaped figure and a dog-bird figure stand on top of the black mountains in the far right of the painting. However, it is the elongated figure in the foreground with an open mouth shape emerging from his hand that holds our attention. Green Paradise Lost: Freedom is an auto-portrait (self-portrait). Cyrille has placed himself in the composition in the guise of a leaf-headed nègmawon22 who is attempting to escape from the effects of colonization and imperialism. An oversized bumble bee holds the center of the piece, its bulging eyes capturing the beauty of the landscape but remaining fully aware of the socio-economic and human devastation wrought on this tropical space that continues to be, using Césaire’s words, “paradise, this soft rustling of palms.”23

In Tropical Aesthetics of Black Modernism, Samantha A. Noël extends the “tropicalization” discursive framework that art historian Krista Thompson initiated in her generative book An Eye for the Tropic: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque and introduces the term “tropical aesthetics,” which is “an effort to enact the naming of place.”24 Borrowing Women’s Studies scholar and cultural geographer Katherine McKittrick’s trenchant term, “sayability,” Noël suggests that “sayability” allows for a geographic aesthetic that “enables agency” and a “grammar of liberation.”25 Therefore, “tropical aesthetics allows for a visual articulation that enacts a different way of knowing and imagining the world.”26 Here I am reminded of the concept of konesans in Haitian Vodou—a way of knowing and being in the world. Konesans considers “different types of knowledge and power,” allowing not only for what we know, but how we know it. It expresses the understanding that, “knowledge is more than a matter of mastering empirical facts and abstract theories.”27

Konesans allows for a different way of world-making, of living and being in the world, one deeply rooted in contes and folklore, one that foregrounds emancipatory practices and familial memories. Thus, Cyrille’s otherworldly landscapes and “tropical aesthetics” allow for a visual epistemology that imagines and konnen (knows) the world differently. I am suggesting here that the grotesque and the unknown could be both disturbingly beautiful and alluringly acknowledgeable. In a work such as Heaven (2021), long-legged, animal-like figures with bird-like beaks crouch on top of a mountain. They crowd underneath a tree whose descending branches are filled with apple-shaped figures, these “strange fruits” bearing eyes and open mouths and huge teeth. Beyond the grotesque figures, the pale yellows, blues, and pinks of the water and sky meet in the middle ground of the composition. While it might be hard to fathom Heaven as an aesthetically pleasing piece, what is visualized in this image is the importance of the sea and water—elements that were essential to his grandfather’s economic life as a fisherman. What draws our eye back to the painting is the inventiveness of a world filled with emotion and metaphorical content. Bathed in rich vivid colors, Cyrille’s paintings convey a prescient atmosphere, one that honors the imaginary human-animals, human-plants “reborn in the colors of [his] memories”28 without losing the stories that they animate.

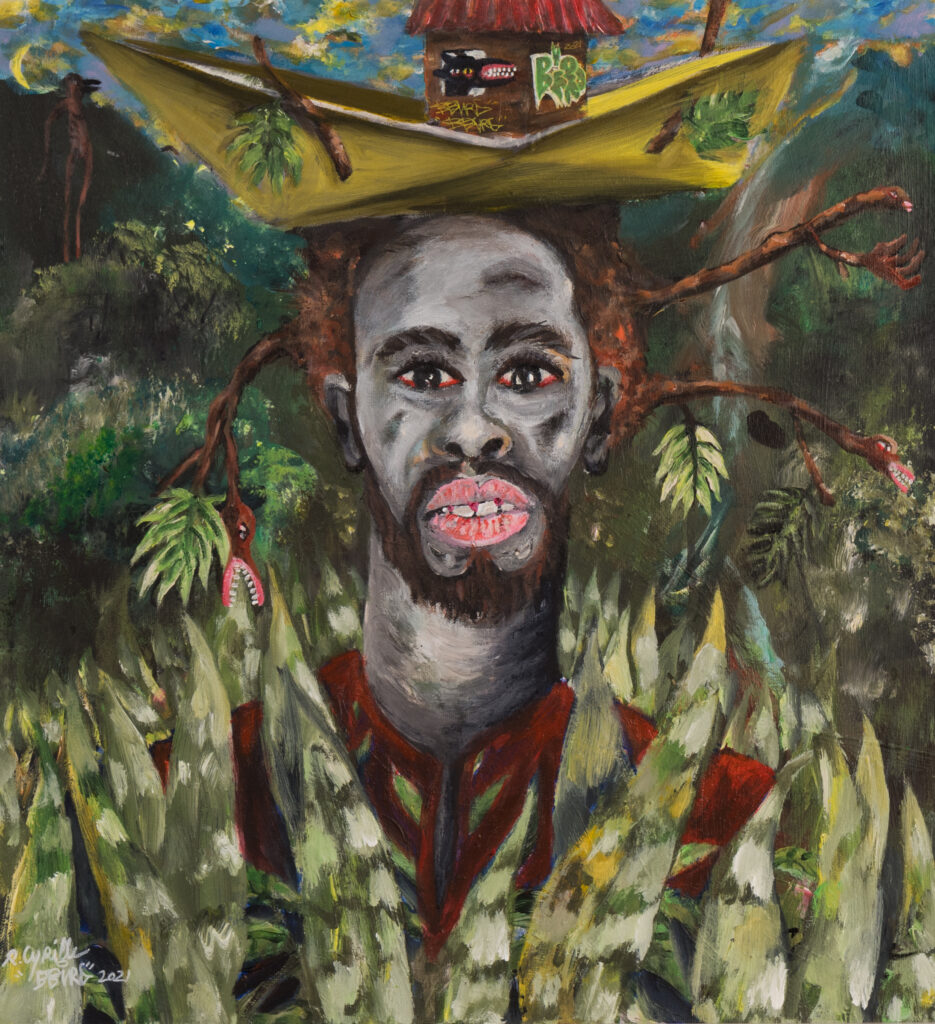

Many of his paintings engage in a dual processing of reality and imagination that underscore the tensions between Cyrille, the painter, and B. Bird, the street artist. A piece such as the auto-portrait Green Paradise Lost: Lost in the Vegetation (2021) brings together these two artistic identities. The image of a boat is made central in the composition; it sits on Cyrille’s head as the lower half of his body is engulfed in dense marks that create lush green leaves and vegetation reminiscent of the foliage scenes by French post-Impressionist Henri Rousseau. In the boat, a house sits precariously with the B. Bird tag and a big-toothed, dog-headed figure. There is forlorn expression on his face, one that is accented by the full ruby lips and red rimmed eyes. In Ronald Cyrille aka B: Bird, Let Me Fly (2017), the artist blends stories from his personal life, his “artistic vocabulary,” and popular American culture. The title is taken from the rap song by African American musician, rapper, and songwriter DMX. Once again, the desire for freedom is suggested in this self-portrait. Cyrille’s human head is replaced by that of a rooster and his figure is encased in a small boat surrounded by wild green dasheen bush leaves and bright yellow hibiscus flowers—both representative of Caribbean flora. The inclusion of the boat evokes the metaphor of migration and escape. What obfuscates the symbol of the boat is the death that oftentimes comes as a result of this search for freedom. What I find fascinating about Ronald Cyrille aka B: Bird, Let Me Fly is illustrated by the second stanza of DMX’s song which poignantly and imaginatively alludes to death over captivity:

Either let me fly or give me death.

Let my soul rest, take my breath.

If I don’t fly I’ma die anyway.

I’ma live on, but I’ll be gone any day.

Either let me fly or give me death.

Let my soul rest, take my breath.

If I don’t fly I’ma die anyway.

I’ma live on, but I’ll be gone any day.

Cyrille’s singular ability to distort elements enables us to move beyond the images and enter a space that is an ardent embrace of the absurd. His work is daring, innovate, generative, and requires interdisciplinary modes of investigation. They provide an opening—an ouverture—to critically examine inchoate artistic frames and forms of creativity that capture the melodramatic characteristic of the Caribbean landscape. In fact, as the artist says, “In my work the landscape is a place where everything can happen, and nothing has to be normal.”29 Perhaps we can apply the tenets of surrealism here as a discursive and criticaltool, one that offers the opportunity of reflection to explore one’s cultural context within the dynamic and imaginative possibilities of imaginative freedom and inventive liberté. Then, a very different story emerges about contemporary Caribbean art and about the producers of that art. It is one that animates their lives and artistic practice both within the agentive space of the personal and within the traditions of global art practices. It is then, as Césaire reminds us “this land, ours, can only be what we want it to be.”30

- Haitian proverb which translates as: “Beyond mountains are mountains.”

- Suzanne Césaire, “Poetic Destitution,” in The Great Camouflage: Writing of Dissent (1941-1945), edited by Daniel Maximin and Translated by Keith L. Walker, Wesleyan University Press, 2012, 25.

- Annette K. Joseph-Gabriel, Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire, University of Illinois Press, 2019, 28.

- Joseph-Gabriel, 28. These seven short essays were published earlier in the Martinican cultural review, Tropiques between 1941 and 1945. Tropiques (1941-1945) was founded in 1941 by Césaire, Aimé Césaire, René Ménil, Lucie Thésée, and Aristide Maugée.

- Césaire, “The Great Camouflage,” 40-41.

- Joseph-Gabriel, 40.

- See “Poetic Destitution” (1942), “Malaise d’une civilisation” (“The Malaise of a Civilization”) (1942), and “Le grand camouflage” (“The Great Camouflage”) (1945).

- Ronald Cyrille, interview with the author, July 22, 2021.

- Tatiana Flores and Michelle A. Stephens, “Relational Undercurrents: Toward an Archipelagic Model of Insular Caribbean Art,” in Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago, editors Tatiana Flores and Michelle A. Stephens, Duke University Press, 2017, 15.

- Ibid.

- Michelle Stephens, “What Is an Island?: Caribbean Studies and the Contemporary Visual Artist,” Small Axe, Volume 17, Number 2, July 2013 (No. 41), 11.

- Guadeloupe is made up of five islands: Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and Les Saintes are all connected by water.

- Ronald Cyrille, artist statement, accessed August 1, 2011, https://www.ronaldcyrille.com.

- Interview with artist, 2021.

- Ronald Cyrille, email message to the author, 7/13/2021.

- Interview with the artist, 2021.

- Keith L. Walker, “Translator’s Introduction: Suzanne Césaire and the Great Camouflage,” The Great Camouflage: Writing of Dissent (1941-1945), edited by Daniel Maximin and Translated by Keith L. Walker, Wesleyan University Press, 2012, xi.

- Suzanne Césaire, “The Malaise of a Civilization,” in The Great Camouflage: Writing of Dissent (1941-1945), edited by Daniel Maximin and Translated by Keith L. Walker, (Wesleyan University Press, 2012), 30.

- Lauren L. Nelson, (2020), “Suzanne Césaire’s Posthumanism: Figuring the Homme-plante,” Feminist Modernist Studies, 3:2, 162-179, 163.

- Interview with the artist, 2021. Emphasis mine.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. During this conversation, Cyrille referenced the public monument, Le Marron Inconnu/The Unknown Marron, by Haitian sculptor, Albert Mangonès erected in Port-au-Prince, Haiti in 1967.

- Walker, “The Great Camouflage,” 43.

- Samantha A. Noël, Tropical Aesthetics of Black Modernism, (Duke University Press, 2021), 16.

- Noël, 16.

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, 2006, (University of Minnesota Press), xxiii.

- Barbara Tomlinson and George Lipsitz, “American Studies as Accompaniment,” in American Quarterly, March 2013, Vol. 65, No. 1, 14.

- Cyrille, artist statement.

- Interview with the artist, 2021.

- Césaire, “The Malaise of a Civilization,” 33.