When ah start to wine ah have no control

Carnival Baby

De Carnival fever is in me soul

Carnival Baby

When ah hear dem pan like ah gone insane

Carnival Baby

De Carnival blood running in meh vein

—“Carnival Baby” by Calypsonian Lord Kitchener

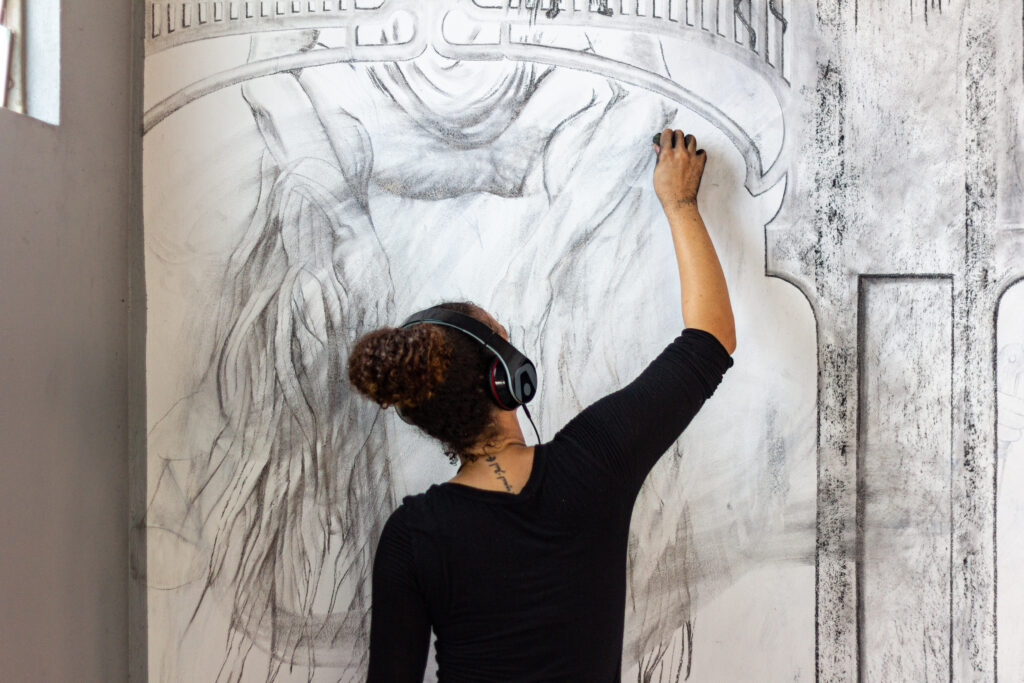

Artist Shannon Alonzo is wearing headphones when she enters the gallery. She steps onto the red platform in front of an expansive charcoal drawing on the wall. A mesh mask covers her face, and a striped stocking hangs from her apron. She walks toward the worktable at the outer edge of the platform and picks up a rubber eraser and some charcoal. She seems unaware of the small audience of curious onlookers. I wonder what music she is listening to as she quietly removes her shoes and approaches the center of the long wall. The charcoal drawing that is spread across the surface is organized like a Rorschach test, the black-and-white imagery repeated left and right like a mirrored reflection on either side of a central gap. The mural presents a screen of interweaving limbs—barren tree branches, disembodied arms and legs. Toward the middle, two gyrating dancers sprout large hands where their heads should be, which in turn clench two faces. Even though Alonzo is masked, it is evident that she is the one represented in the double portrait. The faces seem to fix the viewer with their silent stare. But there is nothing fixed about this image.

Alonzo raises both arms and, with a sweeping gesture like a butterfly stroke, drags her palms across the drawing’s surface, leaving long streaks of smeared charcoal. She squats and then pushes up to give amplitude to her movements. She leans to the right and then to the left as she works over the surface. She grasps the eraser and begins to rub, smear, and smudge large areas of the drawing. And then, with the charcoal, she begins to draw over the remnants of the earlier work, transforming it into something else.

Alonzo created Play ah mas, Play yaself in 2023 at the Bakehouse Art Complex in Miami as part of a Caribbean Cultural Institute (CCI) Fellowship through Pérez Art Museum Miami. “Play ah mas” is a Trinidadian expression meaning to join in a Carnival procession or masquerade 1 This is the third project in as many years in which Alonzo has explored the theme of Carnival through the production of large charcoal murals that she transforms through a process of performative erasure and reconfiguration. These works share common images, a visual language that she has developed to explore the enduring power of Carnival and how its traditional characters and rituals are resurrected each year in ways that manifest its spirit of resilience, resistance, and liberation.

The title of the work invokes Trini patois, a nation language, to reference the way in which Carnival brings together large numbers of masqueraders to form a collective body, but simultaneously, empowers individual participants to be “yaself”/yourself, encouraging them to throw off social restrictions and to manifest a true, if transitory, expression of freedom. What does it mean, Alonzo wonders, for multiple bodies to exist as one entity? The individual becomes subsumed in the energy and movement of the collective. Yet while you are part of a band, you are encouraged to have your own agency. That merging of the self with the mass finds expression in the hybrid figures of composite body parts and multiple limbs that populate the drawing.

These syncretic creatures are a collage of images gathered from multiple sources, a reflection of Alonzo’s passion for history and research. At the outer edges of the composition, locked arms grasp the upward-reaching branches like strong-arm guardian figures protecting the jubilant revelers. This gesture, for Alonzo, is a reference to Canboulay, which in Trinidad is often regarded as the precursor of modern-day Carnival and its significance as a space of resistance and rebellion. Derived from the French term cannes brûlées (burnt canes), the celebration was first performed by enslaved peoples working on sugarcane plantations during the early 19th century, and it included drumming, singing, and dancing as well as stick-fighting competitions using stalks of cane or wood called bois. It continued into the post-emancipation era, when efforts by the British Colonial government to restrict the celebrations resulted in the Canboulay Riots of 1881. 2

In researching the often-contested history of Canboulay, Alonzo was struck by anthropologist J. D. Elder’s account of the confrontation between masqueraders and the colonial authorities in which he describes how the stick fighters locked arms as they advanced, each holding a bois in one hand and a flambeau in the other to create a flank or wall of physical resistance against the authorities: “I thought this was an interesting visual to think about how the masquerade binds us together within the space,” she explained. 3

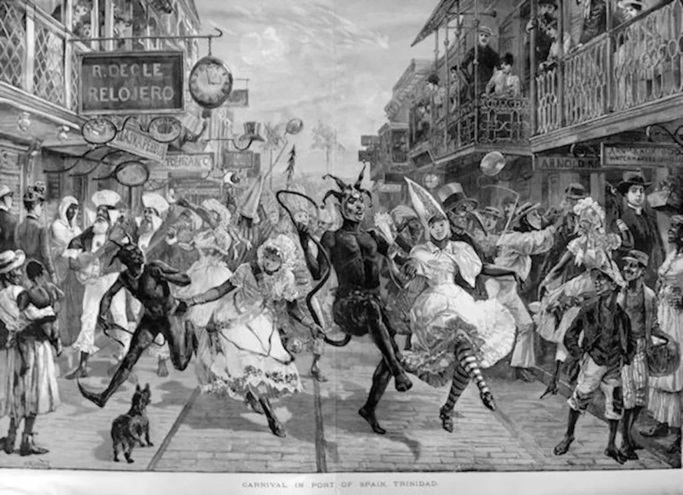

The striped stocking is another image that recurs across the mural and is echoed in the costume Alonzo wears during the gallery performance. It references a late 19th-century print by British illustrator Melton Prior titled Carnival in Port of Spain, Trinidad. Produced for The Illustrated London News in 1888, half a century after emancipation, the scene is regarded as the earliest visual representation of Carnival in Trinidad. 4 The image depicts a jubilant procession down Frederick Street in Trinidad’s capital, which is crowded with masqueraders and spectators. Within traditional Carnival or Ole Mas, these characters serve to mock the elites. The elaborate dress and exaggerated movements ridicule the pretentiousness of the upper classes. At the center is the devil, often understood to symbolize the slave master. The character was known by a variety of names including Jab Jab or Jab Molassie, a reference to the dark molasses or oil that covers the character’s body. He is accompanied by two female characters in frilly lace dresses and pale face masks, with the one on the right sporting striped leggings. Men traditionally played female characters such as Dame Lorraine and dressed to exaggerate curvaceous or buxom attributes. Other well-known characters, such as the Fancy Indians and Sailors, can be seen in the distance along with a troupe of musicians. The diverse makeup of Trinidadian society is evident in the crowd of spectators.

Trinidad Carnival, which is celebrated on the Monday and Tuesday preceding Ash Wednesday, is one of the most influential street festivals in the world, combining elements of European, African, Indian, and Indigenous cultures. 5 The prominence given to this creolized festival in The Illustrated London News attests to its renown. Yet throughout the 19th century, the colonial authorities made proclamations and implemented measures intended to regulate and control participants’ behavior, which they regarded as rowdy, immoral, and potentially dangerous. These included prohibiting dance and torchlight processions, requiring licenses to hold practice drum sessions, increasing police presence at Carnival activities such as stick fighting, creating edicts such as the 1884 Peace Preservation Ordinance, and passing laws that prohibited the wearing of masks. The masqueraders often rebelled, finding creative ways to subvert the restrictions and to retain their cultural celebrations in the face of oppression. 6

Alonzo references these prohibitions in printed words such as “notice” and “mask,” which emanate from the multi-limbed creatures perched in the trees. She is interested in the tension between the policing of Carnival, or the attempts to restrict and regulate it, and the underlying spirit of Carnival, which has always been rooted in a history of rebellion, subversion, and mockery of authority. What is it about the mask that makes it dangerous or desirous? Either threatening or empowering, the mask can be understood as a screen or a mirror in the presentation of character or identity. There is an outward appearance that is on display to the public or demanded by those in power, and then there is the inner self, the authentic self. As an extension of this, Alonzo explores the relationship between the conscious self and the subconscious self, the ways in which the two coexist, and how, through the vehicle of performance, a space for them to weave in and out of one another and thus comingle is created. These questions lie at the base of the mirrored, symmetrical structure of the mural and Shannon’s performative interaction with it.

Shannon also questions the perspective presented in the 19th-century print, which was produced by a British artist for a British publication. She cites historian John Cowley’s observations that Prior’s image is aligned with descriptions of Carnival found in archives of the period, and yet, even at the time of its publication, its accuracy was questioned. 7 How, she wonders, might she interrogate such a representation in the contemporary moment in a way that more authentically reflects the spirit of the Carnival from an “insider” perspective? How could she connect with the Carnival of the past to retrieve other narratives—to decolonize the representation, to take ownership of that representation, to construct an image that in its physical manifestation is truer to the performative, ephemeral, transformative, nuanced, layered experience of Carnival? How could she allow new images and new voices to emerge into visibility and occupy space in ways that reveal new narratives of the past? One doesn’t replace the other but rather comes out if it.

Alonzo’s Carnival creatures are an amalgamation of multiple sources that deliberately morph the past and the contemporary. The gestures of the gloved hands that seem to emerge from her self-portraits like horns or a jester’s cap are based on a photograph of a Carnival participant Alonzo found online. She also incorporates images based on photographs she records of herself performing in the studio, embodying a character, “as if I were on the road.” 8

She gives particular focus to the female body in Carnival and to the ways women move or feel permitted to move within the Carnival space as a site of liberation. Female participation in Carnival has changed over the years from a predominantly spectatorial role in the 19th century to a very active, dominant role as masqueraders, organizers, and designers today. “I’m interested in how that space on the road created a space of agency for women,” Shannon explains, “and what it means for us to perform together, as well as how that individual agency is expressed.” 9 Alonzo’s performance in front of the mural is informed by the vehicle of Mas, and that spontaneous, intuitive flow of bodies within the Carnival space. She describes the process not as an erasure but rather as a transformation, one that speaks to the ephemeral, transitory nature of the celebration while retaining the residual presence of Carnivals past.

De Carnival blood running in meh vein

I always remember my teenage daughter telling me the saddest day of the year is the one after Carnival, because you must wait a whole year for the celebration to come again. Carnival is indelibly woven into the fabric of the Caribbean. Like blood running in your veins. Alonzo is intrigued by the visceral power yet ephemeral nature of this annual event; it exists for a brief time and retreats or dissipates until it reemerges the following year. What happens, she wonders, to the Carnival during that in-between time, in the gap or space between celebrations? Where do these rebellious characters go? These questions intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were prevented from gathering in groups, borders were closed, and Carnival was cancelled.

Shannon was in England when the pandemic began. She was enrolled in the research-based master’s program in Creative Practice at the University of Westminster, but as things were looking increasingly precarious, she decided to return home to Trinidad. She has spent much of her life moving back and forth between the UK and the Caribbean. This transient, diasporic existence has heightened her awareness of the experience of being between places. The nostalgic attachment to Trinidad as “home” that this experience fosters informs much of her work.

Shannon Alonzo was born in 1988 in St. Joseph, Trinidad and Tobago, and at the age of seven, traveled with her mother to Britain, where she spent the next nine years. When at the age of sixteen, she moved back to Trinidad, where she completed secondary school, she was struck by the fact that her education in the UK, which she had regarded as comprehensive, had not included the history of the Caribbean despite its importance to the story of the British Empire. 10 This realization heightened the sense of belonging or rootedness she felt within the physical space of Trinidad and fostered a desire to explore historical narratives in the region and to think about how they have impacted contemporary life.

After graduating from secondary school, Alonzo taught for a year before traveling back to England to pursue a bachelor’s degree at the London College of Fashion. Returning to Trinidad, she worked in the local fashion industry, as well as with Carnival designers including Peter Minshall and the Callaloo Company. She gradually migrated toward a broader visual arts practice, which led her to a master’s program that encouraged her to pursue her research interests in Carnival and to think critically about the methodologies behind her work. This was particularly true once the pandemic compelled her to return once again to Trinidad, where she completed her studies online.

Looking for suitable studio accommodation, Alonzo was fortunate to find Alice Yard, an important contemporary art space in Port of Spain. Alice Yard was established in 2006 by architect Sean Leonard, artist Christopher Cozier, and writer and editor Nicholas Laughlin as a site for artistic conversations, exhibitions, residencies for artists and writers, performances, and film screenings. 11 This became the location for a trilogy of murals entitled Subterranean Sentiments of Belonging (2020) that marked the beginning of Alonzo’s investigation of Carnival’s past, present, and future.

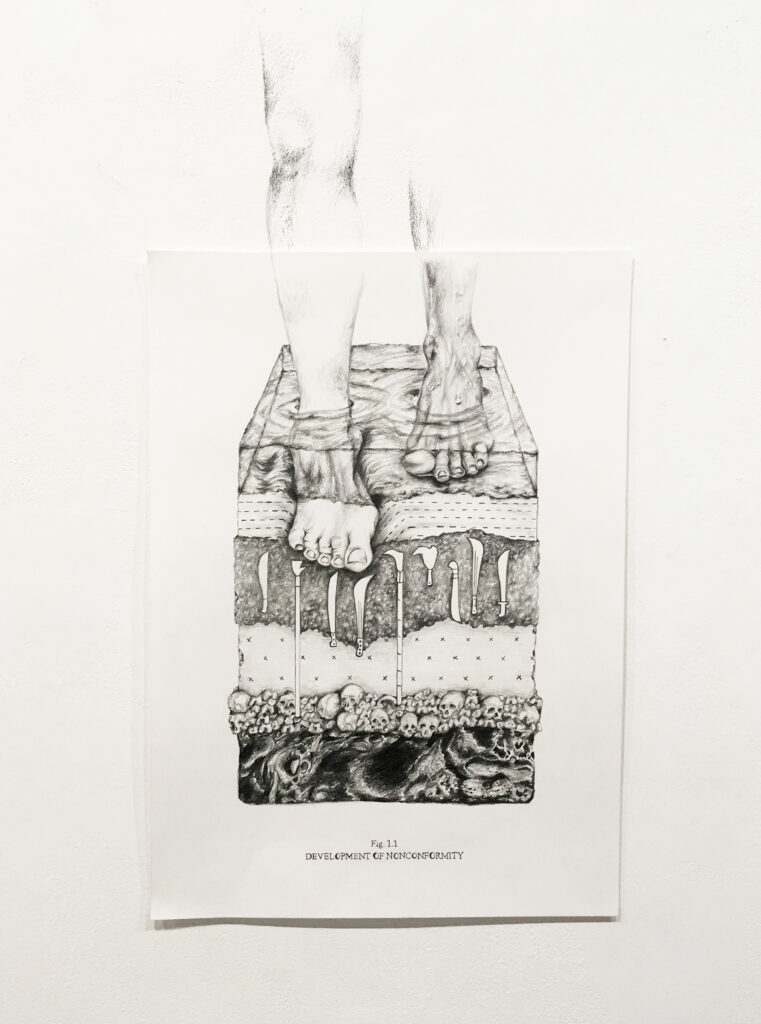

While still in the UK, Alonzo had experimented with drawings on paper that resemble diagrams of archaeological cross sections. Feet and hands press down into sedimentary layers that contain images referencing Caribbean geography, history, and culture—a human geography. Challenging the limitations of the paper’s edges, Alonzo extended the drawings onto the supporting walls, an indication of the direction in which her practice would quickly evolve. These ideas carried over into Subterranean Sentiments of Belonging with the focus now on Carnival and the scale of the drawing expanded to accommodate the epic nature of her theme. “It became a marriage of these ideas of belonging and rooting, with Carnival as a vessel for that as a way for myriad peoples from all over the world to root themselves in a particular environment.” 12 Alonzo sees Carnival as an archive of stories and diverse experiences that are retained and recounted through the traditional characters of Ole Mas. When Carnival ends each year, these characters seem to disappear, only to be resurrected the next. The characters, she explains, become subterranean.

In her master’s thesis, Alonzo introduces the term “imagined archaeology,” which is inspired by Saidiya Hartman’s notion of critical fabulation, and the possibilities that are opened by the ability to construct new and expanded narratives in the face of the absent or partial archive. 13 Alonzo’s aim is not only to embed herself within the physical space of Trinidad but also to unearth its subterranean past with an approach that “seeks to excavate the layers of history embedded within Carnival action.” 14

In the first wall drawing, we see the origins of the locked-arms motif that appeared at the outer edges of Play a Mas, Play Yaself. Here, seven pairs of locked arms form a disembodied barricade across the composition. They hold stalks of sugarcane, bois, and agricultural tools such as a machete or cutlass, a bill, and a halberd that in this context serve as weapons. The overall effect is a rhythmic repetition of verticals across the band of crossed arms, evoking a musical score or the repetition of percussive beats.

Two of the bois morph into stilts supporting a stilt walker who crouches down from her elevated position so that only her head is cut off by the composition. The image is based on a photograph of the artist taken at a stilt-walking workshop, but the traditional Carnival character portrayed in this way is the Moko Jumbie. There is a transition, a metamorphosis that takes place from sugarcane to bois to stilts, that speaks to the historical evolution that binds Carnival to the history of enslaved labor in the Caribbean and the collective actions of oppressed laborers in the forms of resistance and riot against the colonial authorities. The Moko Jumbie, one of the most popular characters in traditional Carnival, is the spirit of retribution, who literally rises above the crowd to foresee any evil that may be approaching. The Moko, Alonzo writes, “is eternal, inhabiting the past, present and presumably future spaces, as his character is resurrected by countless performers across Trinidad both inside and outside of the parameters of Carnival.” 15

For Alonzo, drawing is an intimate medium, one that requires the artist to be close to the surface, particularly on a large scale such as in these wall drawings. The representational, sensitive rendering is intricate, time-consuming, and laborious. It requires the artist to be focused and present and even meditative. For her, the process is a conduit through which she can connect with her subject matter in a profound way. The labor required to produce such a work is not inconsequential. But it is equally significant that there is also something provisional or ephemeral about a drawing: It can be erased.

Alonzo scattered piles of charcoal on the floor at the base of the wall, like remnants of the drawing process. For the artist, this served as a way of connecting the imagery to the earth, to tie the objects she was representing to the landscape that they came from and to the roads that the masqueraders move along. It also extends to a consideration of the way in which elements of nature are used within the Masquerade itself: For example, the bois is made from a particular tree—the poui. And it reaffirms the artist’s close association of the ground with a sense of feeling “grounded,” or rooted, at home.

In November 2020, as part of a group exhibition at Alice Yard entitled States of Confinement, Alonzo performed her first transformation of the wall drawing before a live audience, rubbing and erasing areas and eventually using a large brush loaded with white paint, leaving only ghostly traces of the original. The erasure of the image representing Carnival past and the subsequent metamorphosis to Carnival present emphasized the ephemeral nature of the Masquerade and its capacity to transform and evolve as a strategy of endurance and renewal. Alonzo explained the emotions she experienced as part of the process: “The performance ignited within me an unexpected feeling of catharsis alongside loss. The destruction of the artwork, which runs parallel to that brought about by imperial structure, also represents for me a clearing of space to enable rebirth.” 16

In the second drawing, which represents Carnival present, the vertical elements developed into an architectural structure—a bridge or aqueduct of repeating arches that forms a triptych across the surface. The two supporting pilasters extend downward as roots that reach into the depths of the earth. The stilt walker is still visible above the pilaster on the right, and a second one now appears beneath the arch on the left, the stilts replaced by leafy stalks of sugarcane. The right side of the wall is now dominated by a gigantic vulture, a familiar bird known in Trinidad as a corbeau. He bends his gnarled head downward to pull at the strands of the artist’s hair. Her head protrudes from the ground, her body buried beneath the soil. At the top of the composition, a Carnival procession is visible in the distance. Stilt walkers, flag bearers, and a band of masqueraders parade past the exhausted characters resting by the side of the road. While the Carnival continues along its inevitable route, the artist, immersed and cradled in her subterranean realm, claims her roots within the land. 17

The second performance did not take place in front of an audience due to COVID-19 restrictions, but like the others, it was recorded. This transformation leaves the two rooted pilasters and the central archway as a portal, through which Melton Prior’s two main characters advance, rendered in thick, dark charcoal. In contemplating what the future of Carnival will look like, Alonzo reflects on the commercialization of the festival known as Pretty Mas, a source of much criticism, along with the attendant loss of Ole Mas traditions. She observes that it is unclear if this is a dystopian or a utopian future; this seems particularly the case when we recall that this drawing was being made amid the pandemic, when so much of the future seemed unclear. The industrialized scenes flanking the arch along with the storefront clock—a remnant from Prior’s print—suggest an ominous tone at odds with the jubilant prancing of the characters. This alludes to a refusal to be one thing or another, which lies at the core of Masquerade.

While the process of drawing each of the murals was planned and deliberate in that it was based on research and sketches, the process of erasing and obscuring was more spontaneous and performative, even intuitive. This is perhaps indicative of the relationship between the conscious and subconscious that became more predominant in the Bakehouse mural. The video recording that captures Subterranean Sentiments of Belonging, including the transitional performances, was shown at documenta 15 in Kassel, Germany, in 2022 as part of the exhibition contribution organized by Alice Yard. The video not only documents the drawings, which no longer exist, it also captures their evolving nature through Alonzo’s performative interventions and conveys the considerable durational aspect of her process. Of course, time is compressed. This is made evident by the superimposing of one frame over another, in which the artist fades out of view as she simultaneously reappears along a different point of the mural. Watching Alonzo at work, seemingly alone in the studio, isolated with her headphones on, the viewer comes to understand the long, laborious, solitary effort—a discipline but also a ritual. We see drawing as a meditative practice through which the artist can develop a closer connection with her subject matter. Through this process, she opens a space-time continuum that bridges the past and the present, the present and the future. Carla Acevedo-Yates has written: “The Caribbean experience, and Caribbean history, is crucial to our understanding of the modern world, past, present, and future. It is a global history in the making.” 18

De Carnival fever is in me soul

Christopher Cozier has observed: “In a place like the Caribbean, we cannot take the agency of portraiture for granted, in the aftermath of a much longer history of topographical and anthropological representations. The subject position—or the role of the subject—within the frame or field of pictorial representation is highly contested.” 19

Self-portraits recur in both Play a mas, Play yaself and Subterranean Sentiments of Belonging as a way of interrogating and asserting Alonzo’s presence within the traditions of Trinidad Carnival. In Mangrove, an expansive installation commissioned for the 2023 Liverpool Biennial, the larger-than-life portrait of Trinidadian revolutionary Elma Francois dominates one of the walls as the viewer enters the space. Smaller variations of Francois’s likeness cascade across her forehead, like memories emerging from her past, presenting the diverse and multifaceted roles she played throughout her lifetime. Watery blue tendrils encircle her head, weaving their way over her face, around her lips, and through her nostrils. Alonzo makes use of a Surrealist imaginary to express the rich and complex lives of Caribbean women such as Francois, whose experiences, histories and struggles have not been widely represented.

Mangrove continues the artist’s meditations on the connections between Masquerade and the environment in a work that literally wraps around multiple walls in the basement of the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. Alonzo adopts the analogy of the mangrove—a unique ecosystem of tropical trees and shrubs that adapts to the shifting conditions at the borders of land and sea—to think about the way in which Masquerade fosters a sense of rootedness in different, often hostile spaces. Carnival becomes a site of refuge and rooting for communities not just in Trinidad and the Caribbean, but also in the wider diaspora.

The Liverpool Cotton Exchange, originally constructed in 1905, was regarded as a state-of-the art building, with telephones and direct cables linking it to other cotton exchanges around the world. 20 Cotton was the most important commodity in Liverpool at the time, accounting for almost half of the city’s imports and exports, and the Exchange served as the center of a commercial network structured around colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchy. It is an interesting venue for Alonzo’s work given her long-standing interest in and work with textiles. 21 It was clear that her intention was to take over this space and introduce alternate, neglected narratives, honoring the unseen and unacknowledged laborers who were critical to the industry.

Elma Francois (1897–1944) is a remarkable figure in the history of the West Indies, and yet her story and contribution are not widely known. She was born on the island of St. Vincent where, as a child, she worked alongside her mother in the fields picking cotton. After moving to Trinidad as a young woman, Francois became involved with the growth of labor unions and was known as a vocal activist. She helped to found the Negro Welfare Cultural and Social Association (NWCSA), an organization committed to empowering working-class men and women, and she was integral in the labor protests and riots of the 1930s. Francois was the first woman in Trinidad to be tried for sedition and, representing herself at the trial, she won her case. 22

Alonzo regards Francois’s involvement in organizing protests and collective action as its own form of Masquerade—a kind of protest Mas. On the walls surrounding Francois’s portrait, we see the now-familiar images of Alonzo’s visual vocabulary that also attest to Carnival’s roots in revolt—the crossed arms of the Canboulay marchers carrying bois and stalks, cane and halberds. Identifiable are the morphing bodies of revelers with multiple limbs—arms and legs extended with striped stockings like those that Prior depicted. All of these are connected by the network of vines, many painted in bright blue, contrasting with the neutral tones of the charcoal. Other tendrils made of blue-dyed cotton sprout from the walls and weave their way through the space, as if the cotton had returned to nature and was now swallowing up this abandoned site.

The pervasive blue that flows through the space and across the raised floor summons multiple references. It suggests the watery habitat of the mangrove; it is also an oceanic blue, referencing the Caribbean archipelago, as well as the trauma of the transatlantic slave trade and subsequent histories of migration; it is the unstoppable river of Masquerade bodies moving through the streets; but most significantly, it evokes the Blue Devils, popular characters of Trinidad Carnival, who traditionally parade through the streets of Paramin covered in dark blue pigment. That very deep blue has a visceral connection to Trinidad and to Carnival. Collectively, the images act like rebellious voices of the past, emerging through the walls, rising like groundwater through the stone and plaster, bringing to light the lives, the bodies, and the labor that were centered in the Caribbean.

Halfway through the Biennial, Alonzo returned to Liverpool, where over a period of three days, the public could observe her performance of transforming the work. The room was roped off, but the artist was visible through the open doorways. Wearing a voluminous dyed-blue costume along with her headphones, she became immersed in the space, silently erasing, painting out and drawing over the original imagery. Through the transformation, the overgrowth of the mangrove expanded and began to subsume the figures.

Playing Mas is a powerful, visceral thing. The costumes, the masks, the music, the drinks, the crowd all conspire to create an experience unlike any other. As Lord Kitchener sings, it is the life-force, the blood running in your veins. Alonzo speaks with passion about the ways in which the body is liberated during Carnival, moving and navigating through spaces in a way that is different from any other time of year: “We move as one, as in all of us are parts of this one experience and instead of being one body, we are a massive force that expands and contracts on the road during Carnival.” 23 But the power of Mas extends beyond that, and this is where Alonzo’s wall drawings seek to go. Below the surface, whether it is the subconscious or the subterranean or historical past, the spirit of resistance and rebellion is rooted within the ritual and continues to energize this celebration today. Alonzo brings its hybrid, endlessly mutating and subverting forms to light in her drawings, if only for a time.

- “Mas” is a contraction of the word “masquerade.” Caribbean linguist and lexicographer Richard Allsopp explains that to “play mas” means “to participate in Carnival, formerly as one of a group and in disguise, now in costume and usually as a member of a band, joining freely in street revelry.” Allsopp, ed., Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 444. Anthropologists Maica Gugolati and Hanna Klien-Thomas note that Mas “is defined by scholars . . . as a situated performance and multi-crafted art based on a strategy of bottom-up resistance and rebellion against dominant powers. This has historically included the colonial power(s), class discrimination, and hegemonic groups, which existed even following Trinidad and Tobago’s independence. Although the significance of protest and satire might have been reduced in the contemporary manifestation of Carnival in the Diaspora, mainly due to commodification, rebellious and contestive forms continue to exist.” See Gugolati and Klien-Thomas, “The Im/Possibilities of Digitizing Caribbean Carnival,” Makings: A Journal Researching the Creative Industries 3, no. 1 (2022), https://makingsjournal.com/digitizing-caribbean-carnival/.

- John K. Guzda, “The Canboulay Riot of 1881: Influence of Free Blacks on Trinidad’s Carnival,” The Exposition 1, no. 1, The Pan-American, Article 4, November 1, 2012, https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=exposition.

- Shannon Alonzo, interview by the author, March 15, 2024. The article referred to is J. D. Elder, “Cannes Brûlée,” TDR/The Drama Review 42, no. 3 (Fall 1998): pp. 38–43.

- Melton Prior, “Carnival in Port of Spain Trinidad,” Illustrated London News, May 5, 1888, pp. 496–97.

- Avah Atherton, “The Art of Rebellion: The Baby Doll Masquerade in Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnival,” Folklife Magazine, October 18, 2021, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/art-of-rebellion-baby-doll-masquerade-trinidad-and-tobago-carnival.

- Michael La Rose, “‘The City Could Burn Down, We Jammin’ Still!’: The History and Tradition of Cultural Resistance in the Art, Music, Masquerade and Politics of the Caribbean Carnival,” Caribbean Quarterly 65, no. 4 (2019): pp. 491–512, https://doi.org/10.1080/00086495.2019.1682348. See also Gordon Rohlehr, “The Calypsonian as Artist: Freedom and Responsibility,” Small Axe 5, no. 1 (March 2001): pp. 1–26, https://doi.org/10.1353/smx.2001.0009.

- John Cowley, Carnival, Canboulay and Calypso: Traditions in the Making (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 108–110. As cited in Shannon Alonzo, “Embodied Ascendancy: Exploring Collective Belonging and Attachment to Land Through the Trinidad Carnival” (master’s thesis, University of Westminster, 2021), p. 24.

- Alonzo, interview by the author.

- Alonzo, interview by the author.

- That situation has changed only somewhat in the last decade, following the Windrush scandal, Black Lives Matter, the pulling down of monuments, and the belated recognition of Caribbean diasporic artists in the development of British art.

- See Alice Yard (blog), http://aliceyard.blogspot.com/.

- Alonzo, interview by the author.

- Alonzo, “Embodied Ascendency,” p. 8; and Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 2008): pp. 1–14.

- Alonzo, “Embodied Ascendency,” p. 6.

- Alonzo, “Embodied Ascendency,” p. 16.

- Alonzo, “Embodied Ascendency,” p. 16.

- See Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), p. 19, for a discussion of the relationship between “routes” and its homonym “roots” as it relates to migration and the diasporic experience as foundational to the grand globalizing experience of modernity.

- Carla Acevedo-Yates, “On Thinking and Being Caribbean: A Roundtable Discussion,” in Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990s–Today, exh. cat. (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2022), p. 3.

- Christopher Cozier, “Notes on Wrestling with the Image,” in Wrestling with the Image: Caribbean Interventions, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Organization of American States, 2011), p. 9.

- National Museums Liverpool, “A City Built on Cotton,” https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/city-built-cotton.

- Alonzo’s practice includes large, soft sculptures made of fabric. Two of these, Lowest Hanging Fruit (2018) and Washerwoman (2018), were also included in the 2023 Liverpool Biennial.

- Maya Doyle, “A Lion Amongst Men: The Story of Elma Francois,” National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago (blog), June 16, 2021, https://nationaltrust.tt/home/elma-francois-woman-labour-leader/.

- Alonzo, interview by the author.