In this essay, I will focus on a selection of artworks in the collection of Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) by Cuban artists Reynier Leyva Novo (b. 1983, Havana; lives in Houston) and Glexis Novoa (b. 1964, Holguín; lives in Miami). Through close readings of their artworks, I will explore how these artists, both of whom now live in the United States, utilize heroic iconography to emphasize and critique the ways in which state power is exercised. Novo and Novoa, in their own unique artistic voices, engage artifacts of political discourse, such as monuments and newspapers, and consider how language—both written and visual—shapes ideas of history, governance, and power. Their work makes evident the material and forms of heroic political discourse to undermine its legitimizing power in Cuba.

Glexis Novoa and Reynier Leyva Novo are from different generations. Born in 1964, Novoa is a well-known multimedia artist who began his professional career in the late 1980s, when much of the artwork being made in Cuba was politically and socially engaged. By the 1980s and 1990s, many Cuban artists, including Juan Francisco Elso Padilla (b. 1956, Havana; d. 1988, Havana) and Tomás Esson (b. 1963, Havana), were employing images of Cuban heroic icons such as José Martí and Che Guevara to narrate their own personal stories and reflect on Cuban social and political life. These artists were the first generation of Cuban artists to come of age under Fidel Castro and communist rule. Novo is one of Cuba’s leading conceptual artists. He was born in the early 1980s, and his career developed at the beginning of the 21st century—in a milieu made up of artists attempting to refine the meaning of Cuban life in their work while also facing new censorship laws.

In exploring the artworks of Novoa and Novo, I recognize that their language of critique is indirect but argue that it is nonetheless palpable. In her research on socially engaged contemporary Chinese art, Zoénie Liwen Deng explores different modes of non-oppositional criticality under an authoritarian regime. Acknowledging the dangers of a confrontational approach, she writes that artists “might venture slightly off the grid of a given hierarchical structure, pass slightly under the system’s radar, without being crushed by reigning authorities.”1 What I aim to think through in my analysis of Novo’s and Novoa’s appropriation of heroic symbols and imagery are the distinctive visual strategies of criticality that Cuban artists have developed within their own historical contingencies and the political context of authoritarian governance.

Archives of Heroic Memory

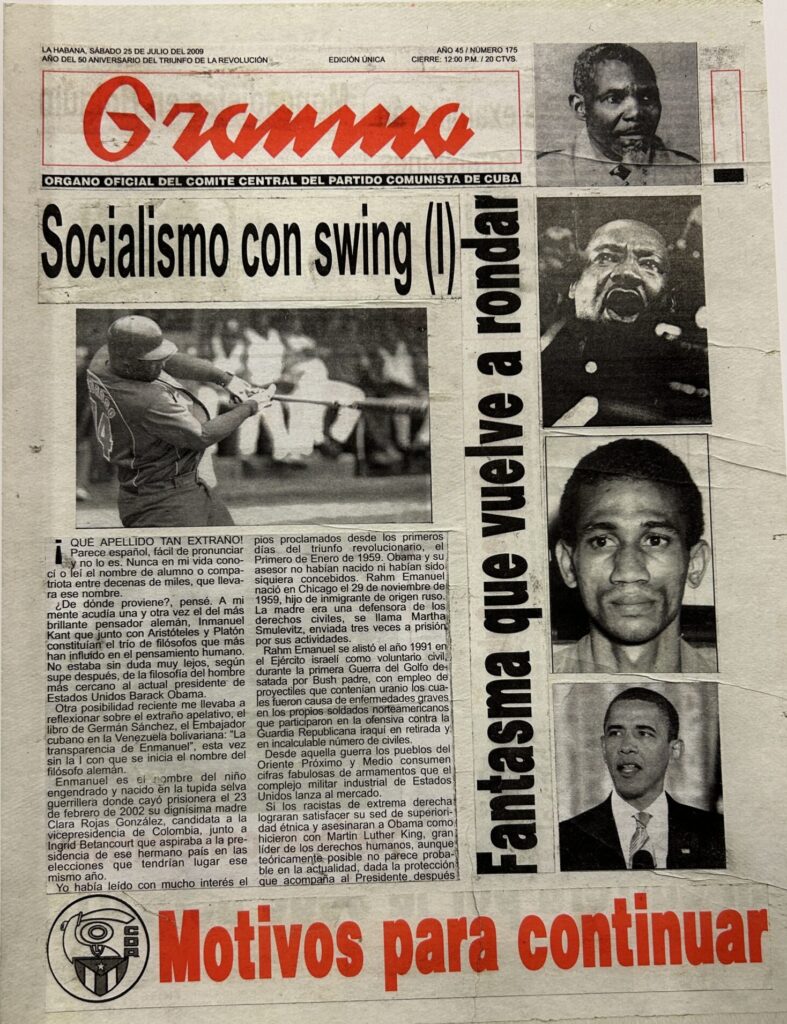

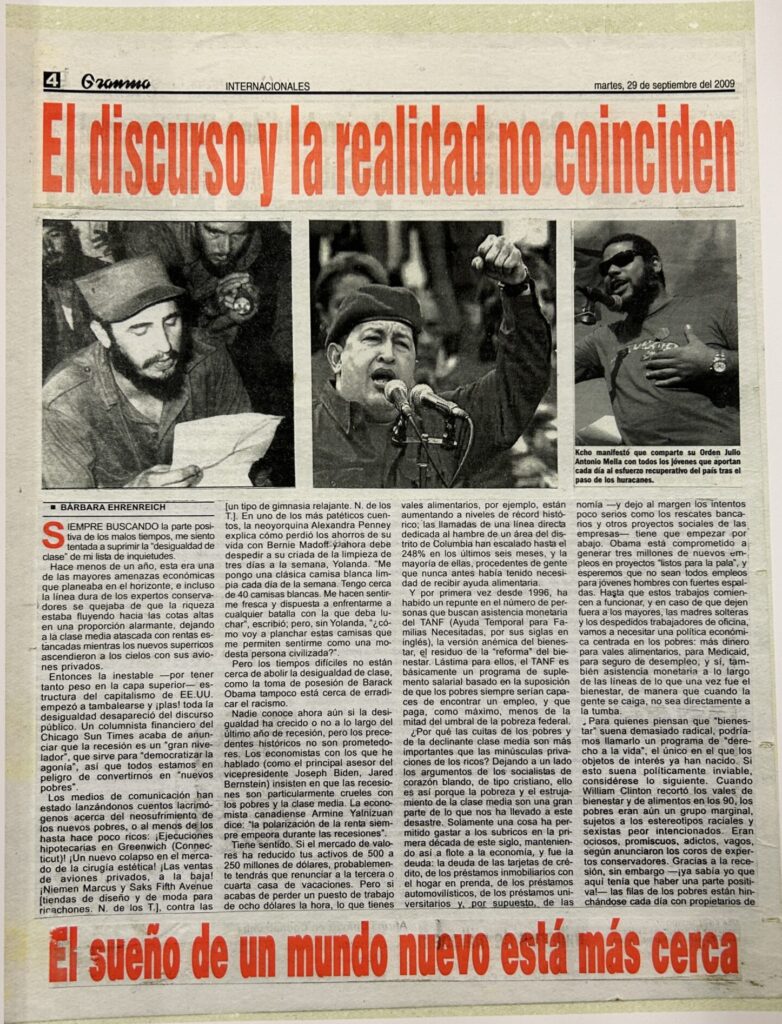

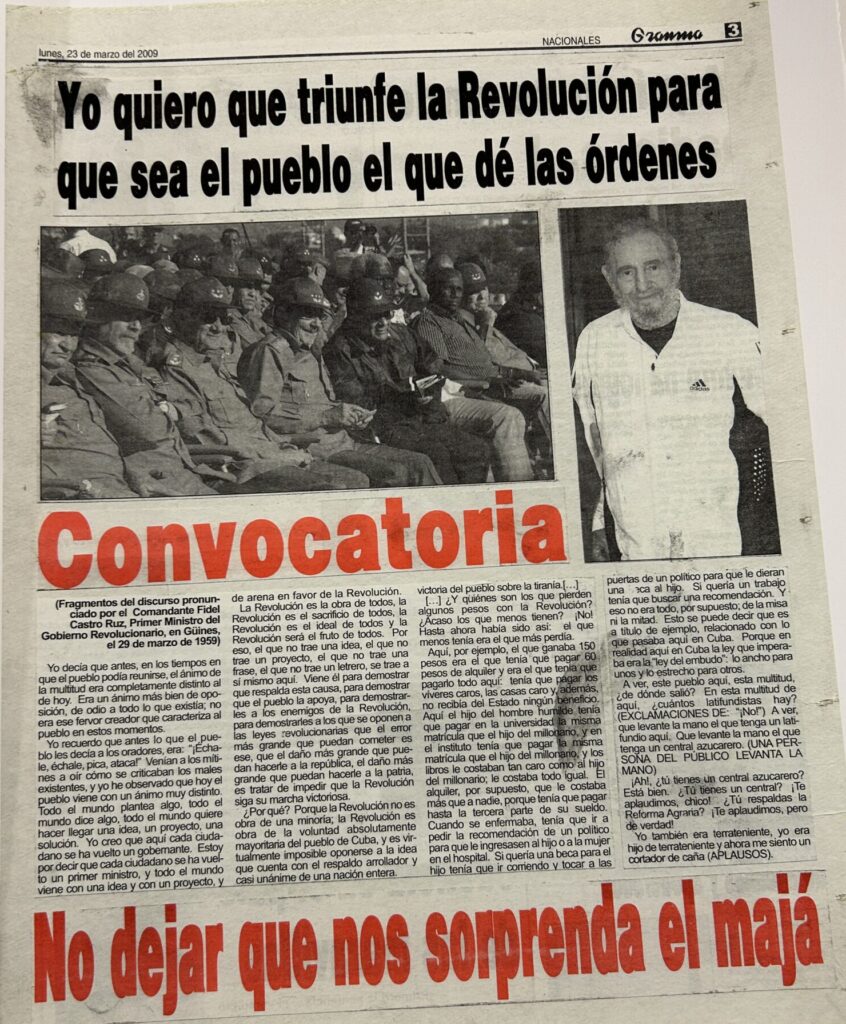

Reynier Leyva Novo’s Páginas escogidas, la historia dia a dia (2007–10) consists of 32 prints that reimagine the newspaper Granma, the “official voice of the Communist Party of Cuba Central Committee.” In this series, the artist appropriated texts and imagery from the pages of the national daily and collaged them into his own newspaper pages. By carefully re-curating articles, texts, phrases, and images from Granma, Novo not only shifted the way in which this official source is presented and consumed, he also created new narratives from it. In doing so, he presented a revisionist history of Cuban national narratives and preoccupations while simultaneously revealing the discursive ways in which state authority is legitimized through print media.

Established on October 3, 1965, Granma was named after the ship that carried Fidel and Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, and other revolutionaries from Mexico to the south of Cuba in 1956 to launch the successful Cuban Revolution. In 1959, Fidel Castro and his army of revolutionaries ended the regime of dictator Fulgencio Baptista, who fled to the United States. Several years later, the new Communist Party of Cuba consolidated the competing political forces that existed after the Revolution. Among the party’s first initiatives was the creation of Granma, which was formed from the merger of Periodico Hoy and Revolución Newspaper, the newspapers of the People’s Socialist Party and Castro’s 26th of July Movement, respectively.2 The first issue of the new publication was printed on October 4, 1965, the day after the announcement of the new party.

According to the blog for Cuba’s Representative Office Abroad, on the night of October 3, 1965, Castro expressed his confidence to the journalists and other workers at the newspaper’s office that they would create “a partisan newspaper of the people and for the people.”3 According to Granma photojournalist Jorge Oller, nearly half a million copies of the first issue were printed and circulated, “many thousands more than that of the twenty capital newspapers combined before 1959.” Published daily in Spanish and weekly online in multiple other languages, the newspaper remains an important source of dissemination of state ideology both within Cuba and throughout the rest of the world. Granma’s website describes that its objective “is to promote through its articles and comments the work of the Revolution and its principles, the conquests achieved by our people and the integrity and cohesion of all our people together with the Party and Fidel.”4

To further understand the significance of Granma as source material for Novo’s Páginas escogidas, it may be useful to return to Benedict Anderson’s insights on nations as imagined communities constructed, importantly, through the development of print capitalism. In his seminal book Imagined Communities (1983), Anderson posits that distinct groups of people perceive themselves as parts of a larger nation-state community with shared common values and affinity—a “deep horizontal comradeship”—through access to daily newspapers that utilize a standardized language, set of ideas, time, and calendar to target a mass audience.5 Based on Anderson’s analysis, we can consider Granma to be an important print technology through which a new national revolutionary consciousness was invented and maintained throughout Cuba after the 1959 Revolution, particularly through the daily repetition of particular types of stories, ideas, and images. Tom Kerkhoff further argues that the tone and form of Granma’s discursive practice and its focus on themes such as Cuban history, the achievements of the policies and programs of the Revolution, the role of Fidel Castro, and the effects of the US embargo can change as the state attempts to “legitimize” or “overlegitimize” itself in periods of heightened social discontent.6

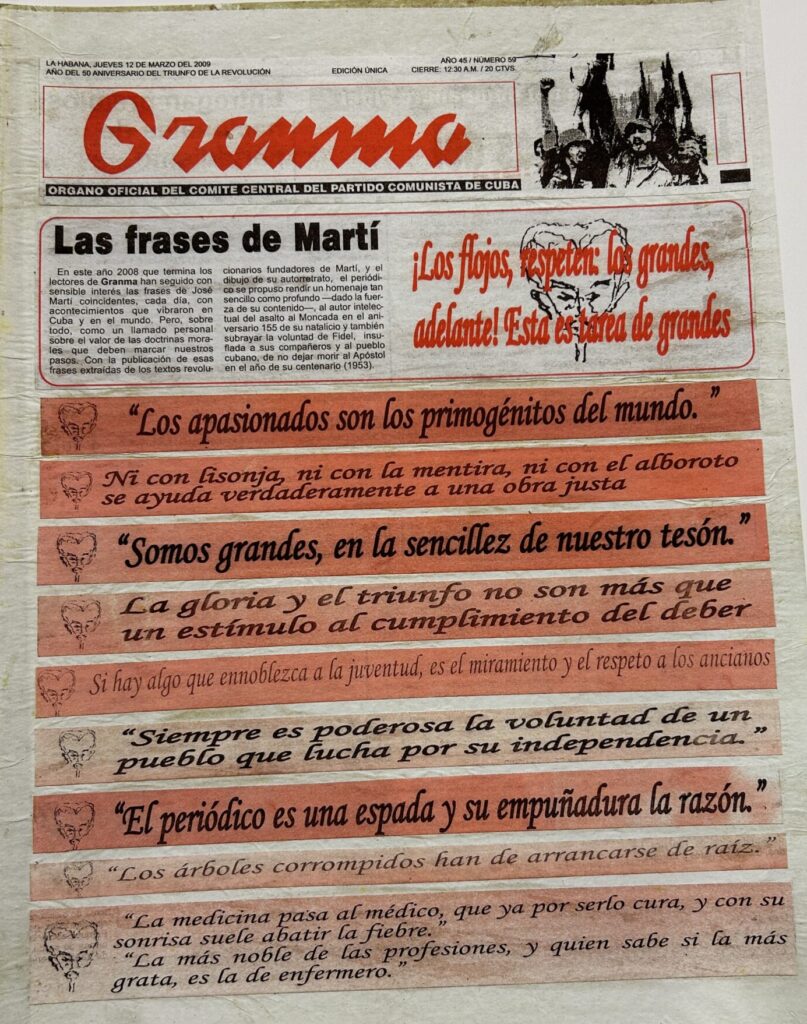

That the nation and state authority are constructed through forms and styles brings us back to Novo’s practice of archival reinvention—of deconstructing, remixing, collaging, and reimagining national memorial forms. In a print from Páginas escogidas titled Las frases de Martí, the artist presents newspaper cuttings from Granma of various quotes attributed to the celebrated 19th-century Cuban writer, educator, philosopher, and nationalist José Martí. Statements such as “Los apasionados son los primogénitos del mundo” (Passionate people are the firstborn of the world) and “Siempre es poderosa la voluntad de un pueblo que lucha por su independencia” (The will of the people fighting for their independence is always powerful) dominate the page. A drawn portrait of Martí accompanies each of the texts, which are printed in different typefaces and ink saturations and on varying background shades of salmon and aged tea stains.

José Martí became a national hero of Cuba because of his dedication to the struggle for independence from Spain. His newspaper articles, poems, and essays such as “Nuestra America” (1891) are lauded for their modernist innovation in prose and for their critical reflections on Latin America and its relationship to the United States. Moreover, his political activism led to the formation of the Partido Revolucionario Cubano, which spearheaded the revolt launched against Spanish rule on January 31, 1895. He would eventually die a month later in battle, though his martyrdom became a rallying symbol for the independence movement. For his writings and involvement in Cuba’s War of Independence, which concluded seven years later, Martí has been lionized, with icons of him conspicuous throughout the 20th century both in Cuba and elsewhere. He is memorialized in public statues, monuments, and murals, and his writings and texts have been reproduced and widely disseminated. The José Martí Memorial, which was completed in 1958, during the last year of Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship (though competitions for the design of the memorial began during Batista’s first regime in 1939), is one such example. This tribute, situated in an elevated garden on the Plaza de la Revolución, consists of a sculpture of Martí seated at the base of a star-shaped viewing tower and museum with a cut-marble facade and Martí quotes encased in tiles. Emilio Bejel argues that the iconization of Martí, whether in the form of monuments, films, or paintings, must be understood in relation to the extension of state power and ideological narratives—and as a metaphoric language for the Cuban social and political body.7

Castro’s government significantly contributed to Martí’s iconization as is evident on the front page of Granma’s first issue, which covers the launch of the Communist Party of Cuba the night before. It features Oller’s photograph of Castro standing at a podium and introducing members of the first Central Committee, who are seated onstage behind him. Behind the members are four large photographic portraits of, from right to left, General Antonio Maceo, second in command of the Cuban Army of Independence; Vladimir Lenin, Russian revolutionary and socialist politician; Karl Marx, German philosopher and political economist; and Martí, whose image is located closest to Castro and the podium.8 Collectively, the portraits within Oller’s photograph serve to narrate the international and local philosophical, political, and revolutionary ideas and activism that shaped the 1959 Revolution. The portraits of Maceo and Martí, in serving as a genealogical connection for the new regime to an older Cuban revolution for “national freedom,” legitimized the new state power represented by the figure of Castro and members of the party onstage. Oller’s photograph documents a well-orchestrated spectacle of the new power in Cuba and illustrates how the heroizing of Martí (and Maceo) would be an important aspect of state legitimation.

In the 1960s, visual arts became a means to instill governmental aims, including via state-sponsored art classes offered by trade unions at Workers’ Centers. Some artists, such as Raúl Martínez (b. 1927, Ciego de Avila; d. 1995, Havana), who became one of Cuba’s most prominent postrevolutionary artists, wanted their artworks to engage directly with the Revolution. By the mid-1960s, Martínez had shifted from Abstract Expressionism to figuration to make his work more accessible. He created portraits of political heroes in a distinct style of painterly naïveté inspired by the ubiquitous murals and graffiti celebrating the Revolution; Luis Camnitzer notes his style was also influenced by the artworks made by ordinary Cubans, which were displayed at Workers’ Centers, and by those made by members of the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR).9 Drawing from these popular aesthetics, he often presented his schematic portraits in multi-panel grid formations reflecting his training and skill in graphic design and his interest in modernist abstraction.

One of Martínez’s early and most well-known honorific works is 15 repeticiones de Martí (1966). In this iconic painting, he presented 15 portraits of Martí rendered in a characteristic heavy black outline and gestural brushstrokes, structuring them in serial form—in three rows of five. These portraits are repeated with slight differences, most notably in the expressive use of color. While some are awash in deep blues, greens, and dark ochers, which gives them a mysterious aura, others are enlivened by juxtapositions of bright greens, pinks, and yellows. Also demonstrative of Martínez’s new style is his famous painting Oye América (c. 1967), which features repeated neo-Expressionist portraits of Castro in mid-speech and gesticulating in front of multiple microphones. Each of the 16 panels, which are organized in rows of four, evidences nuance in pose and facial expression, background design, and color treatment to create a dynamic overall composition—one similar to that of 15 repeticiones de Martí. Martí, Fidel, and Che Guevara are popular subjects in Martínez’s work, sometimes appearing as singular portraits or in series. These heroic figures are depicted in a Pop art style that is likewise Expressionistic, and they evoke a sense of revolutionary urgency.

Martinez’s artworks were significant in the development of political hero iconography in contemporary Cuban art of the 1960s, and they demonstrate the relationship between art and state-orchestrated discourse that also involved the manipulation of images. Whether in the form of murals, schoolbook illustrations, or fine art represented in art exhibitions, Cuban heroic images helped both to create a utopian image of the nation and national development and to promote an ethos of cultural resistance. Since Anderson’s original publication, scholars have shown how visual images were also significant modes through which nation-states were constructed. Novo’s work on Granma, like Novoa’s drawings and installation, reminds us of the synergistic relations among print media, photography, political monuments, and fine art in fostering national identity and political authority in Cuba in the latter part of the 20th century.

Recontextualizing Granma

The repetition of José Martí’s words and portrait in Las frases de Martí draws our attention to the way in which Granma, over time, consciously created a national identity through the multiplication of the sign of the national hero—and how his image, through its association with the 1959 Revolution, has been used for political control. This is evident in Novo’s juxtaposition of Martí’s quotes from the newspaper with Granma’s masthead; the latter features a reproduction of one of the most famous photographs from 1959—the triumphant Fidel Castro with his left arm raised in the air, gun in hand, surrounded by fellow jubilant and similarly armed revolutionaries.

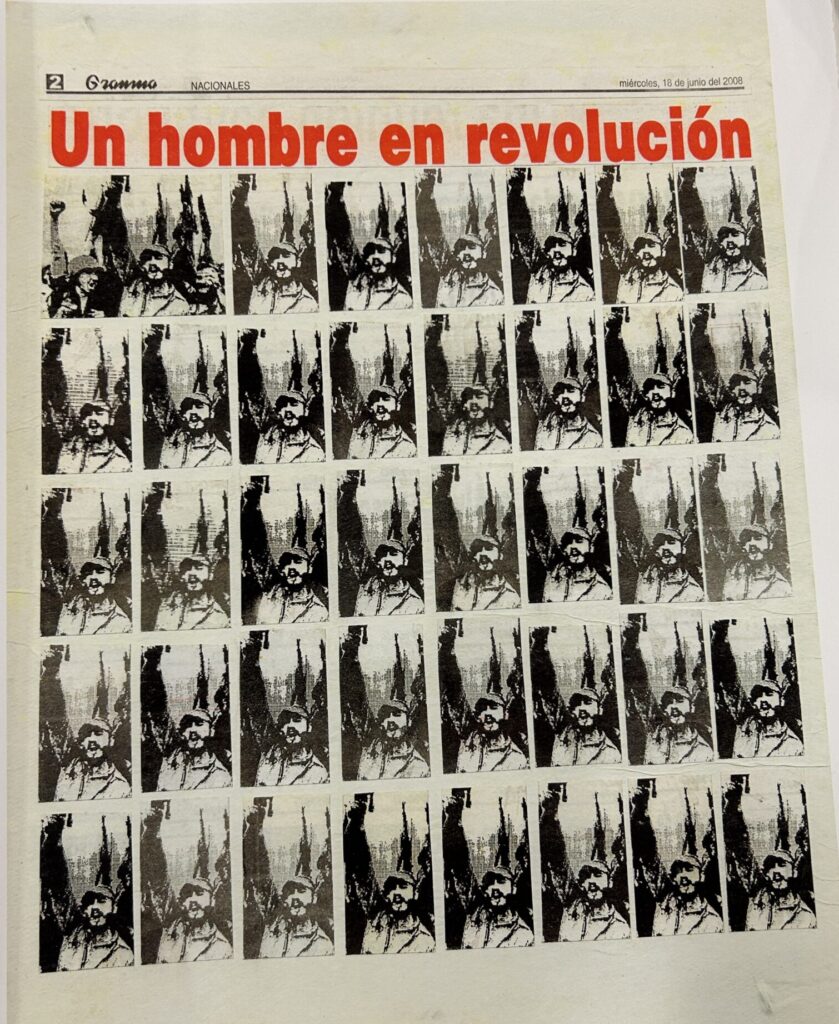

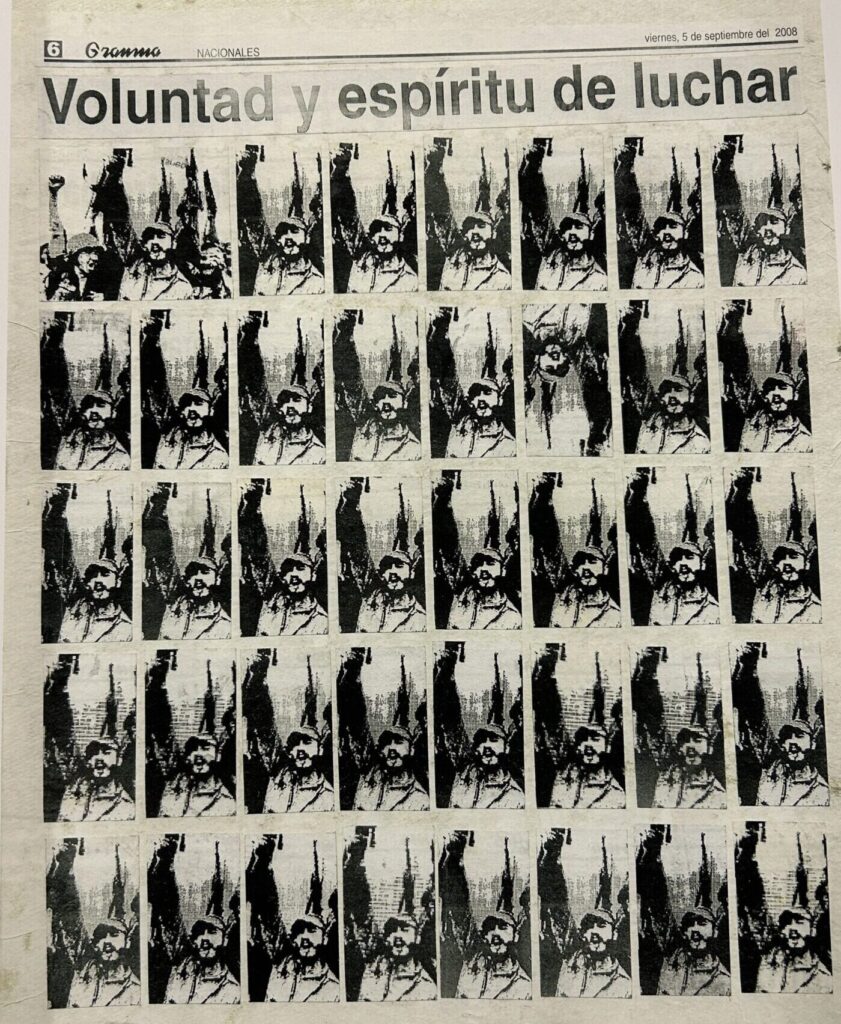

Novo also focuses on the newspaper’s masthead photograph in other pages in the Páginas escogidas series. In Un hombre en revolución, for example, a cutout of the headline “Un hombre en Revolución,” printed in bold red type, is placed at the top of the composition and juxtaposed with 39 cutouts of the photograph in Granma’s masthead. The gray-scale photographic reproductions fill the page and are composed in Martínez’s signature Pop art–inspired, serialized style of painting Cuban icons; each one is cropped to isolate the figure of Castro, with subtle nuances in width, ink saturation, height, and texture created by the folds in the original glued-down paper. The evocation of collective action of the original photograph gives way to a sharper focus on Castro’s iconization. Novo’s satirical representation draws attention to the creation and mass reproduction, dissemination, and consumption of icon images. As such, Páginas escogidas is an artwork in conversation with not only the newspaper but also art history.

American Pop art artist Andy Warhol (b. 1928, Pittsburgh; d. 1987, New York) was interested in the idea of mass consumption in the image-saturated world of mid-century American society and its growing celebrity culture. Employing printmaking and painting, he serially reproduced newspaper pages and mass-produced images of Campbell Soup cans and celebrities like Marilyn Monroe to demonstrate and reflect on the way in which such images and objects unite Americans. Simultaneously, his artworks contemplate how mass production transforms our perception of people, objects, and relationships as consumer products and induce feelings of banality and dissatisfaction that usher the consumer’s interest to other products. Though Warhol’s work lacks the political urgency of Martínez’s and Novo’s work, it offers important reflections on publicity, image-making, and meaning in modern American life in the 1960s. Novo’s project, undertaken in a different cultural context and time, is different from that of Warhol and Martinez in that it also subtly questions the longevity of cultural icons and ideological symbols. The year 2008, printed in the dateline, marked the 49th year of the Revolution, and the reproduction of the 39 images of Castro highlights the dictator’s long reign of power. In another similarly composed page, Voluntad y espíritu de luchar, Novo placed one of the masthead photographs upside down in his grid as a challenge to the “will and spirit” of the Revolution and the distortion of its promises.

This strategy of isolation and repetition is also evident in Las frases de Martí. By deconstructing Martí’s texts in Las frases, that is, by separating them from the context of Granma’s articles and reassembling them as singular events, Novo draws focus to each quotation, wresting it from the banality of the propaganda machine and challenging the viewer to think about the meaning of heroes and their words: What do they mean to you outside of the state’s narration? Are they relevant to your life today? Can they be redeployed to create other stories and meanings? In addition, the work charges the viewer to be attentive to how ideas and images are presented or narrated in public discourse. As noted earlier, typographic design is an important element in Novo’s work, and the slight variations in the presentation of each quote, like his photographic grids, illuminates the importance of style in cultural, political, and historical storytelling. As this series highlights, there is a consideration of style in national narration that can define and determine political subjectivity, social understanding, and response.

Novo’s Páginas escogidas interrogates the newspaper’s role in constructing national consciousness while also providing subtle critique of it through irony. He appropriates the newspaper’s own choice of texts and images to critique its role in a national narration—and employs Martí’s words as a mirror to challenge how the state has reflected the Cuban martyr’s ideas and ideals in the present. Martí’s famous statement “El Periodico es una espada y su empunadura la razon” (The newspaper is the sword and its grip is reason) is the third quote from the bottom in the list on the print but nevertheless stands out, appearing in a bold, Chancery typeface. Like swords, newspapers have varying forms, functions, and users; the quote refers to the enormous power of print media and its potential as an instrument for critical thought. For Martí, newspapers throughout Latin America in the late 19th century were important sites for expressing his ideas, and he created a number of his own newspapers. As a journalist, he wrote about the ethics and role of journalism, calling for the press not only to report but also to be “a watchman that digs up everything,” “to advise,” “to explain,” “to strengthen,” and “guide.”10 Given the intensity of Martí’s iconization in Cuba, his reflections on journalism are often part of contemporary discussions on journalistic integrity and debates on freedom of the press and censorship in Cuba.11 Novo’s artwork beckons us to consider the meanings of Martí’s statements on journalism given the educational, supportive, value-defining, and challenging role of the press is solely in the hands of the state.

While the Cuban constitution recognizes press freedom, it prohibits private ownership of the media. Moreover, its laws allow for jail time and even death sentences for journalists found guilty of acting against the “integrity of the state,” including criticizing the president or other members of the government. Independent journalists, while contending with limited resources, are often subject to harassment, and some have been forced into exile.12 In addition, the state limits social-media access and usage to curb the expansion of platforms that potentially offer expanded and alternative voices and critically oriented public conversation. The 2010 Amnesty International Report, published as Novo was concluding his series, describes Cuba’s restrictions on freedom of expression as “systematic and entrenched.”13 It credits the virtual monopoly on all modes of media, the requirement of practicing journalists to join the national journalists’ association, which is controlled by the Communist Party of Cuba, and the constitutional provisions and vague Cuban penal code as the major mechanisms through which the government maintains control.

Newspapers, like swords, can impart a strong defense and inflict harm both positively (challenging conservative and dominant social and political norms and ideas) and negatively (unjustifiably and through innuendo, misquoting, and lies targeting individuals and groups), and the degree and target of such power depends on who wields it. The more complete version of the popular quote reproduced in part on Novo’s print reads: “The newspaper is the sword and its grip is reason. Only the good ones should use it, and it should not be even for the extermination of men, but for the necessary triumph over those who oppose their freedom and progress.”14 By reappropriating Granma’s use of Martí’s text, Novo’s artwork returns us to the original quote and highlights that in Cuba, it is the state that decides who are the “good ones” and the terms under which “freedom” and “progress” are determined. To be sure, the state, through Granma, positions itself as the “good one.” Through recontextualization, Novo’s Páginas escogidas alludes to the controlling powers that narrate a singular story of Cuban life and aspirations and that position and define the personality of state leadership and authority.

Reynier Leyva Novo. Páginas escogidas, la historia día a día, 2007-10. 32 pages in a box, each: 12 x 15 3/4 inches. Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of Jorge M. Pérez. © Reynier Leyva Novo

Implicit Strategy

Jamaicans have a saying “mi throw mi corn, but mi nuh call nuh fowl” (I threw my corn but I did not call any fowl), which conjures up an image of a person scattering corn on the ground but not inviting a flock of chickens to eat it. The proverb refers to a style of indirect speech. In another version of the popular saying, the term “words” is substituted for “corn.” The phrase “throwing words” suggests making inflammatory comments without clarifying to whom they are directed, thereby averting accusations of personal attack or inviting a direct response. Novo’s Páginas escogidas figuratively and metaphorically “throw words” at Cuba’s apparatus of governance. But because he is using its own vocabulary—its national newspaper, its national hero, its revolutionary discourse—the state must determine whether and to what degree the artwork is an instance of social critique that warrants possible censorship.

Since the 1959 Revolution, Cuban artists have experienced intense periods of restrictions. For example, during the Quinquenio Gris (Five Gray Years) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as Cuba became dependent on the Soviet Union for support, its domestic policies began to mirror the repressive policies of the USSR. Art and culture were severely censored, there was a wave of officially sanctioned homophobia, and Afro-Cuban cultural expressions were targeted. Artists were harassed and jailed, and their livelihoods were curtailed. Raúl Martínez, who was openly gay, was expelled from the School of Architecture, where he taught design; in fact, he was one of many professors who lost their jobs during that time.

More recently, after Fidel Castro’s death in 2016, Cuba’s censorship laws were tightened in the face of growing and publicly active dissenting voices. Decree 349, issued in 2018, requires that all artists, musicians, and performers register for a government license; it also prohibits them from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. Critics of the law note that the wording is sufficiently broad and vague to incite fear and create justification for exposing artists to censorship and harassment. According to an article by Gareth Harris in The Art Newspaper, artists in Cuba have been subject to hostile interrogation, detention, fines, and the cancellation of their shows. Citing Amnesty International, he describes that the “arbitrary application” of the decree has enabled “further crackdown [sic] on dissent and critical voices.”15

In her article “For Cuban Artists, Censure is the Norm,” artist Coco Fusco outlines the multiple instances since 2018 of state attack on artists and journalists and some of the more insidious means of censorship. For instance, she describes state media campaigns, including those waged in Granma, that slander artists and journalists as well as independent media sites abroad. The leveling of such accusations, regardless of their veracity, has led other cultural workers to distance themselves from the accused for fear of repercussions in their own lives and professions. As in the 1960s, state attack has resulted in artists and writers losing their homes and jobs and then being rendered unemployable.16 Regardless of whether authorities choose to act upon it, the decree has created a constant state of anxiety for artists.17

In his article “Culture and Censorship in Cuba,” Errol Boon writes that because the censorship rules are not always clear and specific, artists and state officials engage in an “unpredictable process of interpretation and negotiation.”18 Boons’s interview with Raymond Walravens, founder of Go Cuba!, a Dutch initiative that supports young Cuban filmmakers, reveals that these kinds of negotiations intensify in periods of political instability such as transitions of power—like after Fidel Castro’s death:

What you see is that the authorities take the status quo as a starting point and then look at what the people desire. They then analyse whether giving the people what they want would compromise their position. With that in mind, they sometimes relax control a little to see how that plays out, and whether any further steps can be taken. However, they are just as likely to make a U-turn and tighten the reins again. You might feel like there’s a bit more latitude one day, only to be disappointed the next. Every relaxation of control always goes hand in hand with a tightening. There is the occasional small step towards more freedom, but then the authorities insist on maintaining strict control. . . . Artists and the government are locked in a game where the artists are constantly trying to stretch the rules and find loopholes, while the government turns a blind eye right up until it suddenly doesn’t.19

Perhaps because of the “erratic” nature of governmental response, artists have found ways to present socially and politically provocative artworks that do not prompt censure by the government because, as Walvern notes, “Officially no rules have been broken.” He points to films that adopt an “implicit strategy”—one that engages topical and prohibited subjects using a narrative language that is understandable to the viewer while suggestively pushing the limits of protest. I want to extend this analysis to Novo’s Páginas escogidas and to Glexis Novoa’s Mamayev Square (2011).

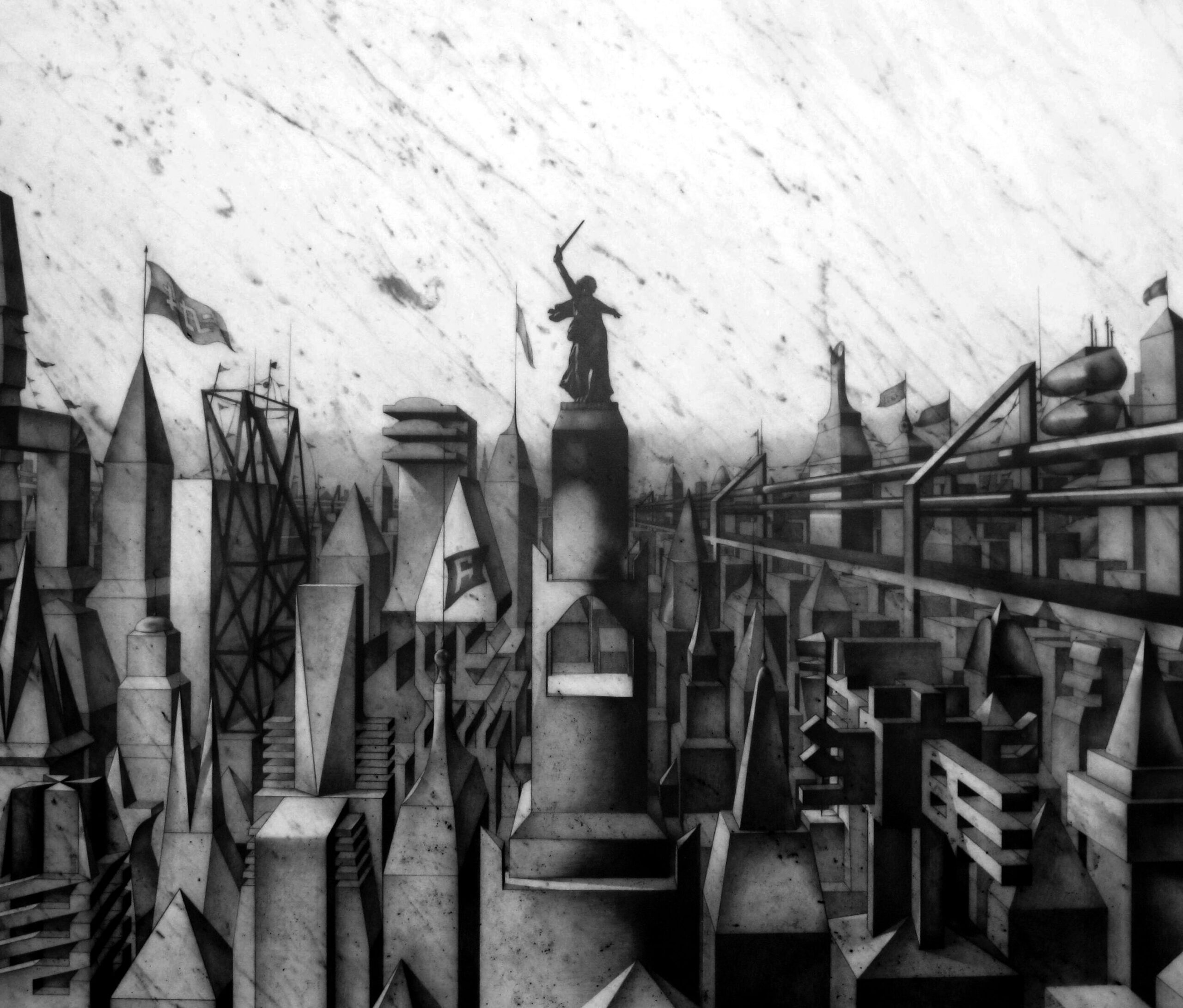

Mamayev Square is a graphite drawing on marble of an aerial view of a surrealistic urban landscape; the city is both recognizable and indistinct. A collage of present, future, and past, the drawing eludes time. The layered, graphic line of the tops of the buildings draws our attention to the center of the crowded composition, where the allegorical statue The Motherland Calls! is visible. This 1967 concrete-and-steel work is located on Mamayev Kurkan, the hill that overlooks the Russian city of Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad). Once the tallest statue in the world, it stands at over two hundred feet, crowning the enormous World War II memorial complex “To the heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad,” which commemorates those who lost their lives in the Battle of Stalingrad, a turning point in the war against Germany.

The statue depicts a female figure whose flowing dress and shawl are inspired by the Winged Victory of Samothrace, an ancient Greek sculpture depicting Nike, the goddess of victory. Symbolizing Mother Russia, she holds a raised sword in one hand while looking back and beckoning the Soviet people to battle with the other, outstretched hand. The memorial complex in which this work is situated is a sacred site of both national mourning and heroic triumph. In his article on the monument, Scott Palmer has shown that it is an example of how postwar monuments and memorials have been used to expand political discourse of unity and party loyalty and to project strength, both locally and internationally.20 For example, according to Palmer, the height of the statue in Volgograd was extended from the initial design of 98 feet tall to more than 200 feet because of the Cold War: Then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev ordered that its height should surpass that of the Statue of Liberty.21

Like a receding memory, The Motherland Calls! lacks detail in Novoa’s artwork. Nevertheless, its dominant position at the center of the drawing recalls the statue’s significance in Russian history-making; such monuments, Palmer describes, are important “artifacts” of the officially sanctioned cult of the Great Patriotic War that developed in the 1950s and 1960s and provided “a new source of legitimacy for the continuing political monopoly of Communist Party leaders.” He writes that stories of the heroism of the soldiers in battle were part of a larger legitimating process that involved creating a national narrative “of collective suffering, salvation and redemptive sacrifice.”22 More broadly, standing among the buildings, the statue’s silhouette in Novoa’s Mamayev Square directs us to ponder the role of architecture and sculpture in narrating and mythologizing national history. Indeed, the dynamic forms of the architecture, partially inspired by the shapes of the Cyrillic alphabet, are actively writing history.

Because the built environment depicted is devoid of human figures and the intimacies of the city’s street culture, it reads as a symbol of power. This critical bird’s-eye view of the construction of national memory and the language of state power in Novoa’s Mamayev Square is emphasized by the heraldic flags atop the spires throughout the drawing and, most prominently, to the left of the statue. Political monuments are often linked to other sites of power. For instance, The Motherland Calls! is featured in the coat of arms of the city of Volgograd and in other commemorative state images such as stamps. And, as iconization of Martí has helped us to understand, such resonant images are also integral to state newspapers and state-sanctioned art and political spectacles. Mamayev Square scrutinizes and critiques these interrelated lexicons of power, but because the artist has reinterpreted them within his own formal codes, the challenge is subtle and ambiguous but nonetheless present.

Given the relationship and impact of the Soviet Union on Cuba’s history, the references to Soviet iconography such as the Russian script and monument in Novoa’s Mamayev Square are, of course, not incidental. Indeed, he made references in his work to Soviet agitprop poster style and symbols early in his career.23 I would argue that the artwork acts metonymically for Cuba’s own legitimizing discourse of national triumph, unity, and heroic sacrifice through the image and political discourse around its own icons, such as Martí. In the overwhelming repetition of the harsh lines of the buildings and other architectural features and in its urban desolation and absence of human interaction, Mamayev Square suggests the oppressive and anxiety-inducing landscape of power in Cuba today.

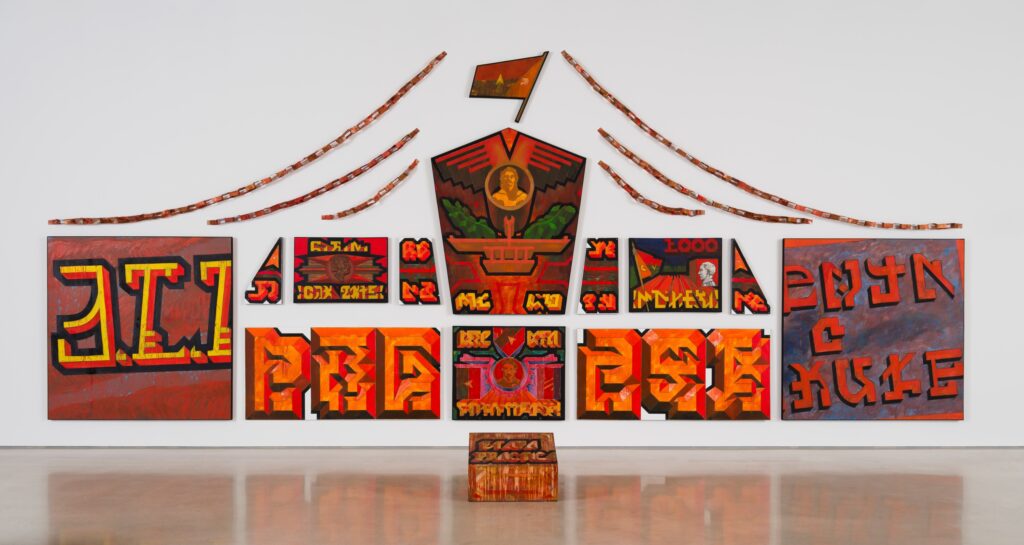

The reference to Cuba and Cuban iconography is perhaps more evident in Novoa’s 1989 monumental wall installation Sin título (La etapa práctica), which distills the country’s revolutionary discourse into specific forms, gestures, and styles. More colorful than his graphite drawings, with shades of red, orange and yellow predominating, the multi-panel mixed-media work draws on the conventions of popular revolutionary imagery and decorative political street parade displays. Like Martínez several decades before him, Novoa was also inspired by CDR images and the wall murals and architectural forms that were created by trade union members for mass rallies. The work depicts portraits of heroic figures, heraldic signs, and reinterpretations of Russian, Indian, and Egyptian script, all of which are enlarged and isolated on separate panels. Unlike some of his word paintings, the texts in Sin título are not legible, yet their bold, sculptural presence in the composition alerts us to other traditions of political significations and to the power of words—written, visual, and sonic—in conveying ideas of power. The low podium in front of the wall installation, the surface of which is painted with text and highlighted in black, suggests a base for a political speaker or pedestal for a political statue. In rearticulating the language of pageantry, the artist calls attention to the power and pervasiveness of heroic, revolutionary discourse. Novoa readily admits that this suggestive strategy employing the tropes, icons, and styles of Cuban propaganda allows him to have both a critical voice and a successful career in Cuba. By co-opting the language of state pageantry and heraldry, he can avoid the censors—though they are of course wise to his intent.24 His work straddles a very fine line.

The strategies of antiheroic critique in Caribbean art are manifold. The indirect language of critique used by Glexis Novoa and Reynier Leyva Novo developed from their own experiences as practicing artists from Cuba. Their work, nevertheless, is part of a larger ongoing conversation within contemporary art of the region. The vicissitudes of 20th-century Caribbean political cultures, shaped by local historical and social dynamics and by Cold War geopolitics, continued relations with colonial powers, and—at the end of the century—the new global players such as China, has challenged the ways in which the Caribbean experiences and perceives ideas of the heroic nation, sovereignty, and governance. Consequently, there is a generation of artists that, emerging at the end of the century, has challenged the mobilization of heroic history, icons, and symbols for political legitimization and governance; recognized the history of violence by Caribbean postcolonial states toward its citizens; and acknowledged the vulnerabilities of Caribbean state leadership and autonomy in global politics. Simultaneously, we also have artists who, through their work, continue to call for the recognition of new local heroes, even as other artists are challenging what that project of recognition means symbolically, materially, and psychologically. These instances within contemporary art draw our attention to the multi-vocality of heroic icons and symbols and to the incomplete work of 20th-century Caribbean nationalist ideals.

- Zoénie Liwen Deng, “‘Be water, my friend’: Non-Oppositional Criticalities of Socially Engaged Art in Urbanising China” (PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2020), p. 32, https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/52347198/Thesis.pdf.

- The 26th of July Movement was a revolutionary movement led by Fidel Castro to overthrow the government of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. After the successful overthrow of Batista, it became a political party led by Castro that was later absorbed into the Communist Party of Cuba.

- “Conquering a Dream: The First Central Committee, the Granma Newspaper and Che’s Farewell Letter (+ Video, Chapter 4),” Cuba’s Representative Office Abroad website, April 9, 2021, https://misiones.cubaminrex.cu/en/articulo/conquering-dream-first-central-committee-granma-newspaper-and-ches-farewell-letter-video.

- “¿Quiénes somos?” [Who are we?], Granma, https://www.granma.cu/quienes-somos. Though the newspaper is the self-proclaimed voice of the Communist Party of Cuba, there are nuances in the way that articles criticizing the government are written and in how the government responds to such criticism. See, for example, Joe Sampson, “Life Inside Cuba’s Communist Party Newspaper Isn’t What You’d Expect,” Media Shift (blog), June 2016, http://mediashift.org/2016/06/granma-newspaper-marks-50-years-eye-future/.

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983; New York: Verso, 1991), p. 6.

- See Tom Kerkhoff, “La Revolución Sigue Adelante Cuban State Discourse in Granma in the ‘Special Period’ and the Post-Castro Era” (master’s thesis, Erasmus University, 2022), hdl.handle.net/2105/65227.

- See Emilio Bejel, José Martí, Images of Memory and Mourning (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

- “¿Quiénes somos?”

- See Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba, rev. ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003).

- “Ideas de José Martí sobre el periodismo,” Cubaperiodistas, May 19, 2020, https://www.cubaperiodistas.cu/2020/05/ideas-de-jose-marti-sobre-el-periodismo/; see also Eileen McGovern, “José Martí and the Politics of Journalism,” Cuban Studies 25 (1995): pp. 123–46.

- See, for example, “Ideas de José Martí sobre el periodismo”; and Ariel Lemes Batista, “Palabra y pluma ardiente: el periodismo de José Martí,” http://www.monografias.com/trabajos23/palabra-pluma-marti/palabra-pluma-marti.shtml#ixzz4SqhXQtLW.

- [1] Loren Sanoval Arteaga, “Cuba: Independent Journalism Officially Outlawed by the Regime,” International Press Institute, March 26, 2021, https://ipi.media/cuba-independent-journalism-officially-outlawed-by-the-regime/; and Suzanne Bilello, “Cuba’s Independent Journalists Struggle to Establish a Free Press,” Committee to Protect Journalists, UN Refugee Agency, Refworld, February 1997, https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/cpj/1997/en/56379.

- Amnesty International, “Restrictions of Freedom of Expression in Cuba” (London: Amnesty International Publications, 2010), p. 4, https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amr250052010en.pdf.

- Pastor Guzmán, “Patria, ese bravío soldado con letras,” Escambray, March 14, 2022, https://www.escambray.cu/2022/patria-ese-bravio-soldado-con-letras/; Batista, “Palabra y pluma ardiente: el periodismo de José Martí”; and “Ideas de José Martí sobre el periodismo.”

- Gareth Harris, “Losing the Battle: Cuba’s Dissident Artists Find Ways Around Censorship Despite Government Crackdown,” Art Newspaper, November 28, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/11/28/losing-the-battle-cubas-dissident-artists-find-ways-around-censorship-despite-government-crackdown.

- Coco Fusco, “For Cuban Artists, Censure is the Norm,” NACLA, January 7, 2022, https://nacla.org/cuban-artists-repression-norm.

- Rubén Gallo, “Is This the End of Cuba’s Astonishing Artistic Freedom?” New York Times, February 18, 2019.

- Errol Boon, “Culture and Censorship in Cuba,” DutchCulture, January 18, 2021, https://dutchculture.nl/en/news/culture-and-censorship-cuba.

- Boon, “Culture and Censorship in Cuba.”

- Scott W. Palmer, “How Memory Was Made: The Construction of the Memorial to the Heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad, Russia Review 68, no. 3 (July 2009): pp. 373–40, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9434.2009.00530.x.

- Palmer, “How Memory Was Made,” p. 394.

- Palmer, “How Memory Was Made,” p. 373.

- Tobias Ostrander et al., On the Horizon: Contemporary Cuban Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, exh. cat. (Munich: DelMonico Books-Prestel in association with Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2017).

- Glexis Novoa, interview by author, December 2023.