Part I

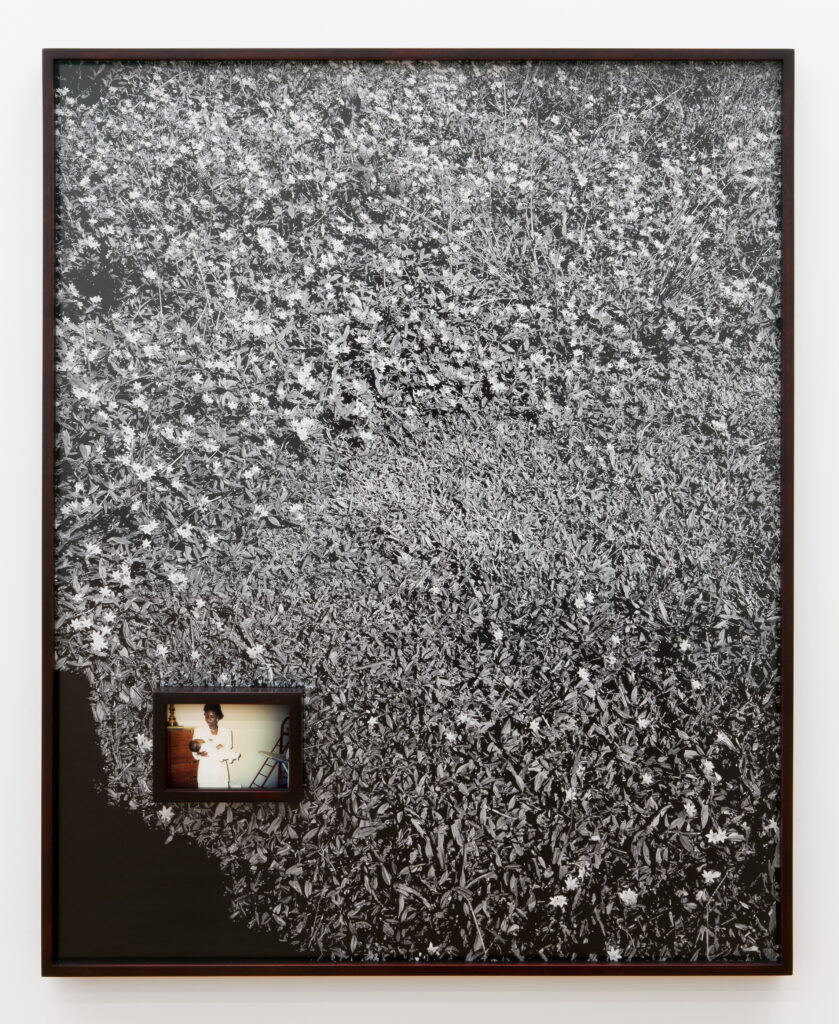

The vastness of the ground in Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1) (2021) by Widline Cadet (b. 1992, Petion-Ville, Haiti; lives in Los Angeles) invites contemplation. Drained of color, the green and brown that might be expected of grass is no longer evident, nor does the pink or yellow of the small blooms in the field catch one’s attention. The flowers in the large-scale black-and-white photograph are difficult to identify—in stark contrast to some of the artist’s color works of flowers reminiscent of bougainvillea, a plant that scales many of the residential homes and other buildings in Haiti.

We can imagine the brightness of their vivid orange or red piercing through the dust and the movement of passersby on a busy street. Instead, Cadet’s black-and-white photograph of the ground asks viewers to spend time with the quietness of an expansive gray scale. Upon further study, an impression in the grass in the center of the picture becomes evident. What has made this indent is also completely open to consideration—as are the reasons Cadet took this photograph in the backyard of her sister’s home in Florida and chose to repeat the image, to different ends, on more than one occasion within her larger oeuvre1.

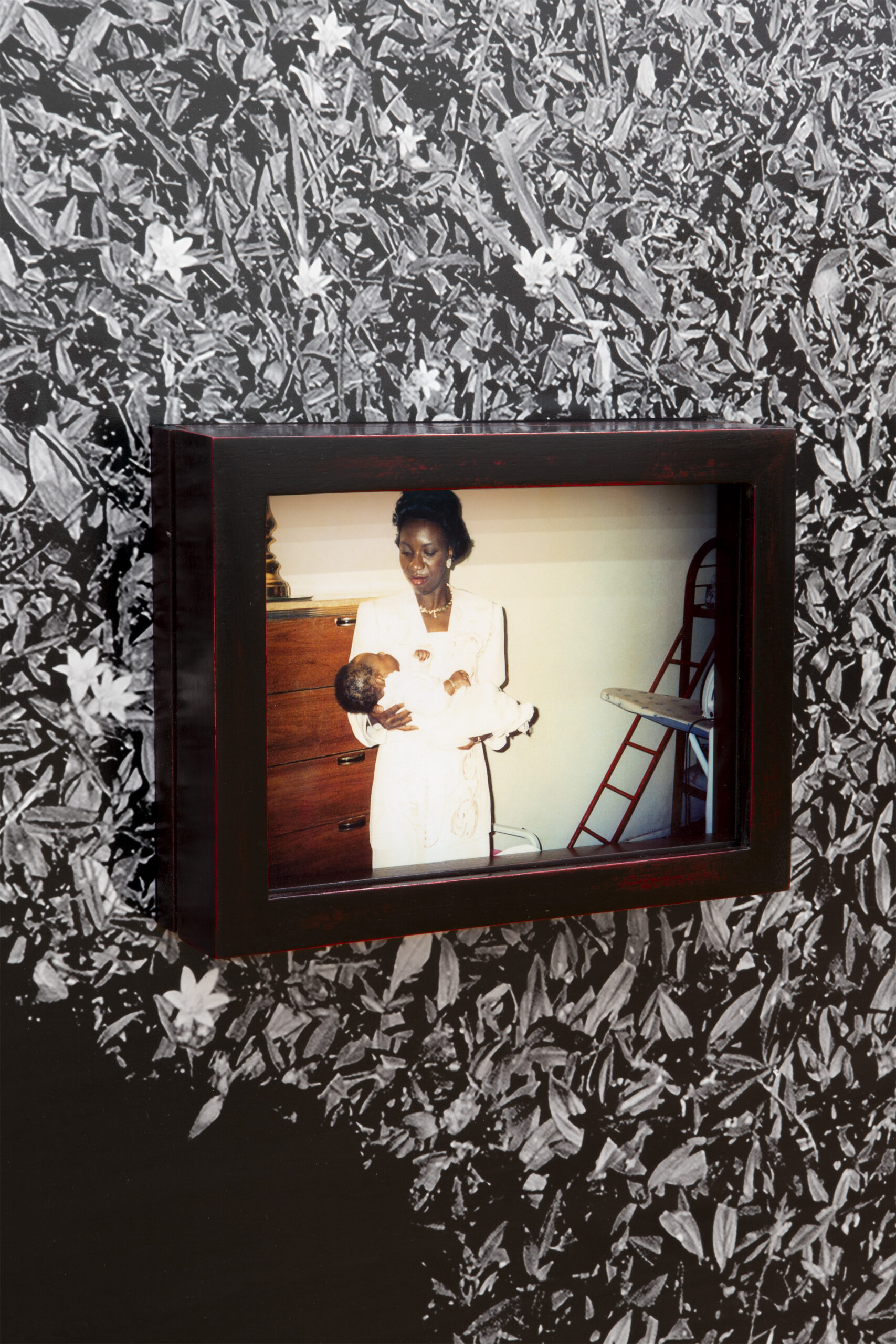

In the case of Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1), the immensity of the space is punctuated by the off-center inclusion of a framed color vernacular photograph attached to the lower left-hand corner of the work, serving as an anchor in the large-scale scene. The inkjet print of this image introduces figures into the frame in a way that combines the quotidian nature of family photographs with the grandeur of a special moment: We see a scene of a woman holding a baby—a family picture of Cadet’s mother and baby sister taken on the occasion of her sister’s baptism more than twenty years ago. To the left of the figures within the small snapshot, there is a dresser and lamp; to the right, part of an ironing board is visible. A red bunk-bed ladder is also in view. Mother and daughter are in a bedroom, among the most intimate and least outwardly performative rooms in one’s home.

The overall body of work by Cadet demands the kind of reverential looking one engages in when moving through a family photo album scaled to fit into the palms of two hands. Yet the large photographic works and arrangements for which the artist has become known take the intimacy of family keepsakes and expand them to the large-scale walls of a gallery space. Viewers bear witness to black-and-white photographs in a rich tonal range, highly saturated color photographs, and multimedia work incorporating film and image-making that has a three-dimensional quality, the latter being an aspect of Cadet’s practice that she aims to pursue further in the next chapter of her art making.2 In the last decade, Cadet has established herself as an artist of note who constructs a personal archive of familial images in the face of absence. Yet this essay takes Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1) as its singular focus to demonstrate a constellation of ideas that lead readers toward some beginning possibilities of framing Cadet’s work and its distinct characteristics.

Since Cadet is a Haitian-born artist inclined to think deeply about her own positionality, it is worth contemplating the distinct Caribbean orientation of her work—more broadly, its attentiveness to the particularities of the Caribbean and the contours of its art and visual culture. Responses to the question of a work’s Caribbeanness can run the gamut from the highly specific to the more holistic, from the flippant to a persistent frustration with how such framings encourage overdetermined ways of thinking. Cadet’s work speaks back to such framing in moving ways, bobbing with and through and around a range of definitive responses, thereby coming up with categorizations that are confidently fluid and flexible. Considering a distinct Caribbean orientation becomes a mode of inquiry that ends up cultivating just the kind of curiosity and awe necessary to engage with the work’s themes, both singularly Caribbean and expansively humanist.

Part II

In Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1), viewers are beckoned to look and then to look again closely at the baby. As opposed to being cradled during an intimate moment between mother and child, the child is held as though being purposely presented to the person holding the camera. The scene is primed for the viewer. Light also directs the gaze. The walls are a bare cream color, amplifying the whiteness of the pair’s clothing and the light that bounces off the shine of the mother’s forehead. There is also a sharp contrast between the calming gray tones of the large, matte photograph’s vastness and the compactness of the bursts of overexposed white saturated areas of the smaller family photograph. In turn, the brightness consumes mother and daughter within this baptismal scene. They visually appear to merge into one figure subsumed in oversaturated white, a symbolic and godly gesture enabled by the camera’s inability to subdue the reflection of light.

The small, internal frame within the larger picture encloses and holds still the light—and the Madonna and Child depiction. Despite the imposing scale of the overall work, which measures 50 x 40 inches, other crucial details come into view when standing in front of Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1). The baptismal scene in the brown wooden frame is attached to the glass covering the larger photograph. When the work is viewed from the side, the smaller, boxlike frame appears to float in front of the larger image. It is there, suggestively ready to be picked up and opened to reveal the keepsake inside. The brown of the frame prevents it from disappearing into the black and white of the background. The augmented, smaller frame becomes a photographic object, thereby reinforcing the “thingness” of vernacular photographs.

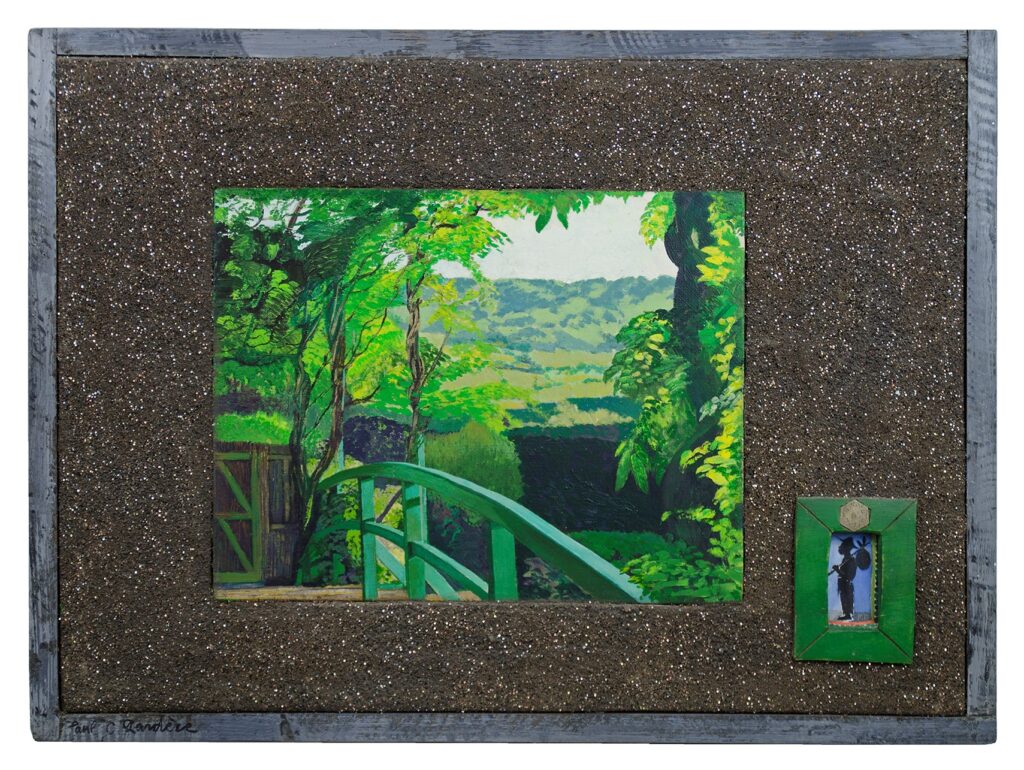

The work evokes examples by other Haitian image makers across time including that of the late artist Paul Gardère (b. 1944, Port-au-Prince, Haiti; d. 2011, New York City) with his penchant for collaging framed inserts into his colorful multimedia works; the conceptual artist Adler Guerrier (b. 1975, Port-au-Prince, Haiti; lives in Miami) and his love for mundane photographs of the flora in his backyard; and contemporary artist Naomieh Jovin (b. 1995, Philadelphia; lives in Philadelphia) and her play with visual depth and the construction of family in her series Gwo Fanm.3

© Estate of Paul Gardère

For other contemporary artists of Haitian descent, although they do not regularly incorporate vernacular photographs into their artwork, the photographs of the everyday often hold space within their creative process. Examples include Didier William (b. 1983 Port-au-Prince, Haiti; lives in Philadelphia) and Manuel Mathieu (b. 1986, Port-au-Prince, Haiti; lives in Montreal), both of whom include vernacular photographs among the paintings and prints shown in their published monographs.4 Outside of this intentional realm of Haitian artists, one would be remiss in overlooking the work of Leslie Hewitt (b. 1977, New York City; lives New York City), an artist who similarly uses small photographic inserts in series such as Riffs on Real Time (2006–9).

As for Cadet’s mentioned influences, she speaks of how the locale of Los Angeles reminds her of Haiti, how the way Black bodies move sets in motion memories of the past, and that the work of American photographer Larry Sultan (b. 1946, Brooklyn; d. 2009, Greenbrae, California) has made a lasting impression on her understanding of photography’s powerful ability to turn the workaday into the extraordinary. In particular, she is drawn to Sultan’s series Pictures from Home (1983–92), a project documenting everyday scenes of the photographer’s aging parents in their Southern California home. The most memorable images in the series capture either his father or mother (or both) within a warm domestic background, engaging in whatever mundane task demanded their attention at the time. Sultan’s work recalls many of Cadet’s scenes of family and pairs of individuals and how the way each subject places a hand or turns a head is a drama worthy of photographic documentation.5

A sense of stark closeness courses through many of Cadet’s works. When she directs her lens at a subject, the technical quickness that enables the aperture to record it is completely forgotten in the quietness, stillness, and intimacy of the representation she captures. In Untitled (Derrick and Tiberius) (2017) from the series Soft, anonymous hands cup a young Black man’s face as he looks toward them with his eyes closed, his nose acting as a compass, pointing in the direction of the person cradling his cheeks. The mostly unseen figure is visible to the viewer only as a set of forearms and hands. In another work in the series, Untitled (Ebony and Gail) (2017), two Black women hug each other within a snow-covered landscape. Both are appropriately bundled in warm clothing as the older and shorter of the two wraps her arms around the other, who looks away from the camera, completely engulfed in the embrace. Together their bodies create a triangular mound of strength. This confluence of forms makes for a powerful image. In Cadet’s development as a photographer, her journey is similarly marked by formative experiences.

Part III

Widline Cadet was born in 1992 in Pétion-Ville, an eastern suburb of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and she spent her early years in Thomassin—a relatively mountainous area not too far from Pétion Ville, which is home to major grocery stores, galleries, cultural institutions, and bookstores.6 At age 10, she emigrated from Haiti to the United States, where she lived in Washington Heights, an upper Manhattan enclave known for the large presence of families with ties to Haiti’s neighboring country of the Dominican Republic. Her formal education as an artist includes earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts in studio art with a focus in photography from the City College of New York (CUNY) and a Master of Fine Arts from the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University. Nonetheless, the most influential experiences in her artistic development happened outside of the classroom and her formal education. For Cadet, moments of profound progress took shape at artist residencies among peer artists and within environments that afforded her the space and time conducive to creating at her own pace and likings. For example, a fellowship at Lighthouse Works on Fishers Island, New York, set her on a path of exploration and creativity unavailable to her in the more confined structure of classroom expectations and the time-sensitive demands of MFA critiques.

Her audience of diverse viewers can be found around the globe, dispersed throughout the many corners of the world where Haitians in the diaspora can be found. These viewers have engaged with her work at well-known New York City institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, MoMA PSI, and El Museo del Barrio as well as smaller venues including sUgAr Gallery at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville and Blue Sky, Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts in Portland. Outside of the United States, she has participated in group shows in Madrid, Amsterdam, and Bristol. Powerhouse institutions including the Studio Museum in Harlem, the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, and the Pérez Art Museum Miami, among others, have acquired her work for their permanent collections. Beyond the sage decisions of museum acquisition administrators, selection committees have recognized and supported Cadet through awards, including the prestigious Snider Prize, which was granted to her in 2020 by the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) at Columbia College Chicago. As MoCP’s chief curator and deputy director Karen Irvine shares, “Widline’s extraordinary talent was apparent from the first moment we opened her submission. Her portraits are considered and alluring, and poignantly speak to issues of visibility and identity.”7

Yet the most important step in Cadet’s legacy-building has happened outside of the coffers of museum permanent collections and the closed discussions of selection committees. Instead, the moments defining her significance as an artist have taken place between and among the individuals who most represent connection and home to her. In Ant yè ak demen (Between Yesterday and Tomorrow) (2023), Cadet loops a short video clip of her mother talking to her in Haitian Kreyòl as Cadet, as the interlocutor, remains off camera. Her mother voices what Cadet herself has discussed many times in interviews. Repeated, again and again through her mother’s looped video, is commentary on the absence of photographs of the women who preceded them in their matrilineal line. For example, there are no photographs of Cadet’s mother’s mother or of Cadet’s grandmother’s mother.

While Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1) is among a triptych of works in which Cadet incorporates old family photographs, other examples from her oeuvre just as readily evoke familial relationships through alternate means.8 She states, “I became very drawn to portraiture as a way of filling a gap that was left by the lack of pictures and documentation of my family history.”9 Her innovative making of an archive speaks to an absence experienced by many, including a significant number of those in Haiti and its diaspora. This shared reality begs the question, What can we glean from the relationship between photography and Haitian families? No doubt photo examples from Haiti and its diaspora from the 19th century to more contemporary times exist. However, the historical contours of photographic access, output, and informal and formal archiving practices in Haiti are underexplored areas of research inquiry.10

What remains evident is that Haitian photography studios, past and present, have operated in places where clients can find them.11 They exist on busy avenues. They exist in town squares, near churches, around transportation hubs, and in areas where pedestrians are likely to pass by their front doors.12 But their output—the various photographs taken there, printed out, handed to patrons, and then carried home as keepsakes—is sometimes preserved but more often misplaced, lost, or damaged. Aside from studio photographs, those images taken at home by fellow relatives and friends may have found their way abroad through migration. Other such pictures were safeguarded in photo albums stored in drawers or pinned to walls and then eventually lost as adjacent to tragedy or succumbed to fading by the sun or to the wetness of humidity or rain. In many cases, the photographs of “that-has-been” were never taken at all.13 This is the state of Haitian vernacular family photographs, a state in which Cadet intentionally intervenes and takes charge for the sake of creating her own archive where one did not exist before. If “photography is a technology through which memory can be materialized and stored outside the body, and in the process transmitted across generations over time,” then Cadet puts this technology to good use.14 Her conceptual practice unfolds in the space of the United States, grounded within a desire for visual legacies within the Haitian diaspora.

So much of the scholarship on quotidian family photographs positions this kind of vernacular photography as the possibility for telling histories that have been left out or overlooked. Such photographs become outlets for charting family histories and worldbuilding in the face of absence and loss. Photographs, it is said, and especially vernacular photographs, can step in as the antidote, the sliver of evidence that proclaims that she or he was there and mattered.15 What happens when this possibility of existing in the world through the photographic image is not possible? In Cadet’s work, does the power of absent images hold more significance than the ones she re-creates to honor their loss?16 And so too, how do we make sense or make room for a different kind of presence? In turn, “When does one decide to stop looking to the past and instead conceive of a new order?”17 Cadet proposes her own answers through a rich kind of visual recollection of the familial as well as through language.

Part IV

The title Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1) serves as a kind of poem.18 Within a single line, Cadet shares a sentiment universally exchanged between caretakers and their kin and one that demonstrates the pedagogical intent of parenthood. This is the phrase that teaches children about the weight immigrant parents often place on the shoulders of their offspring. Half in Haitian Kreyòl, half in English, this bilingual text does more than simply illustrate Cadet’s link to the linguistic worlds of Haiti and the United States. The act of writing Kreyòl holds significance; to not only speak in Kreyòl but also to write it demonstrates its importance to the many registers through which dynamic languages function. Likewise, it is notable that the Kreyòl phrase precedes the English translation, hinting at Cadet’s allegiance to one aspect of her heritage.

This poetic ode goes wherever the artwork goes—the title serves as a constant reminder of Haiti’s presence. No longer solely translated for those in geographic locations in which many Haitians reside, the bilingual title allows Haitianness to take up space in a range of different contexts of display—from the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, where individuals of Haitian descent will surely count among those gracing the gallery halls with their presence, to places like Madrid and Oregon, where such demographics are more meager and the audience less known. Indeed, a “poem takes on a depth of field that undercuts linearity. Instead of existing on a horizontal plane solely, the poem becomes vertical and lateral in its simultaneaous exploration of consciousness.”19 Through translation, a sentence that starts its focus on “you” in Kreyòl, shifts concentration by beginning with “I” in English while communicating the same message through repetition. So too does the title loop parallel worlds—like the film of Cadet’s mother, bringing us back to Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #1 (I Put All My Hopes On You #1). Cadet’s work offers a powerful constellation of recurring ideas constantly moving from one space to another with concerns for the familial and the familiar at the very center. As viewers, it’s worth celebrating these “archives that have finally begun to appear” in order to imagine “the stories of how they, and we, came to be.”20

- For example, the same image (without the vernacular photograph) can be found within her series Soft. See the artist’s website, https://www.widlinecadet.com/recently/2017/1/11/3et8vz7bqscgjd802b7f5x6ud46fyr

- Widline Cadet, in discussion with the author, October 10, 2024.

- See “PhMuseum 2021 Photography Grant,” Gwo Fanm, PhMuseum, https://phmuseum.com/submissions/gwo-fanm-1.

- Adeze Wilford, ed., Didier William: Nou Kite Tout Sa Dèyè, exh. cat. (Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, 2023). “Immense Appreciation: Milo Matthieu,” Forgotten Lands: Caribbean Art and Dialogue, vol. 6, Neo Carib Visions (2024): pp. 23–39.

- See especially her body of work called Home Bodies.

- We can assume that many of these establishments have suspended operations given the ruinous and escalating gang violence in Haiti following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021.

- Karen Irvine, email message to author, January 14, 2025.

- The triptych includes Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #2 (I Put All My Hopes On You #2) and Sé Sou Ou Mwen Mété Espwa m #3 (I Put All My Hopes On You #3)

- Widline Cadet, “Q&A: Widline Cadet,” interview by Zora J. Murff, Strange Fire, January 17 2019, https://www.strangefirecollective.com/qa-widline-cadet

- The limited existing scholarship on the topic includes Barbara Buhler Lynes, ed., From Within and Without: The History of Haitian Photography, exh. cat. (NSU Art Museum, 2015).

- Again, we can assume that many of these establishments have suspended operations given the ruinous and escalating gang violence in Haiti following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021.

- For more information on Haitian studio photography, see Marilyn Houlberg, “Haitian Studio Photography: A Hidden World of Images,” in “Haiti: Feeding the Spirit,” special issue, Aperture, no. 126 (1992): pp. 58–65, https://archive.aperture.org/article/1992/01/01/haitian-studio-photography.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (Hill and Wang, 1981), p. 77.

- Krista Thompson, “The Evidence of Things Not Photographed: Slavery and Historical Memory in the British West Indes,” Representations 113, no. 1 (2011): p. 56, https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2011.113.1.39.

- For example, see Brian Wallis and Deborah Willis, African American Vernacular Photography: Selections from the Daniel Cowin Collection, exh. cat. (International Center of Photography, 2005).

- This question is informed by Jennifer Nash’s scholarship on the intersections of loss and photography. Nash, “Picturing Loss,” in How We Write Now: Living with Black Feminist Theory (Duke University Press, 2024), pp. 69–90.

- Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 100

- For an example of how vernacular photographs inspire poetry, see Shuriya Davis, “Butterly Hymnals That Won’t Disturb the Pleasant: Complacency, and Other Lullabies,” RISD Museum, Manual, no. 14—Shadows (2020), https://risdmuseum.org/issue-14-shadows/artist-art. For reflections on poetry in Kreyòl from an earlier period, see Marie-José Nzengou-Tayo, “Haitian Poetry in Creole: The Nineteenth-Century and Early Twentieth-Century Works,” in A History of Haitian Literature, ed. Marlene L. Daut and Kaiama L. Glover (Cambridge University Press, 2024), pp. 194–213.

- Fred d’Aguiar, “A Theory of Caribbean Aesthetics,” Anglophonia Caliban/Sigma 21 (2007): p. 93, https://doi.org/10.4000/caliban.1881.

- Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (Writers and Readers., 1993), p. xix.