“My militant mother hungry for freedom

sensitive to the sufferings of the oppressed

unwilling to accept any injustices

enamored of literature and passionate about history,

making us quiet when our father was working,

writing tirelessly, with her mysterious script…”

— Ina Césaire, “Suzanne Césaire, My Mother”1

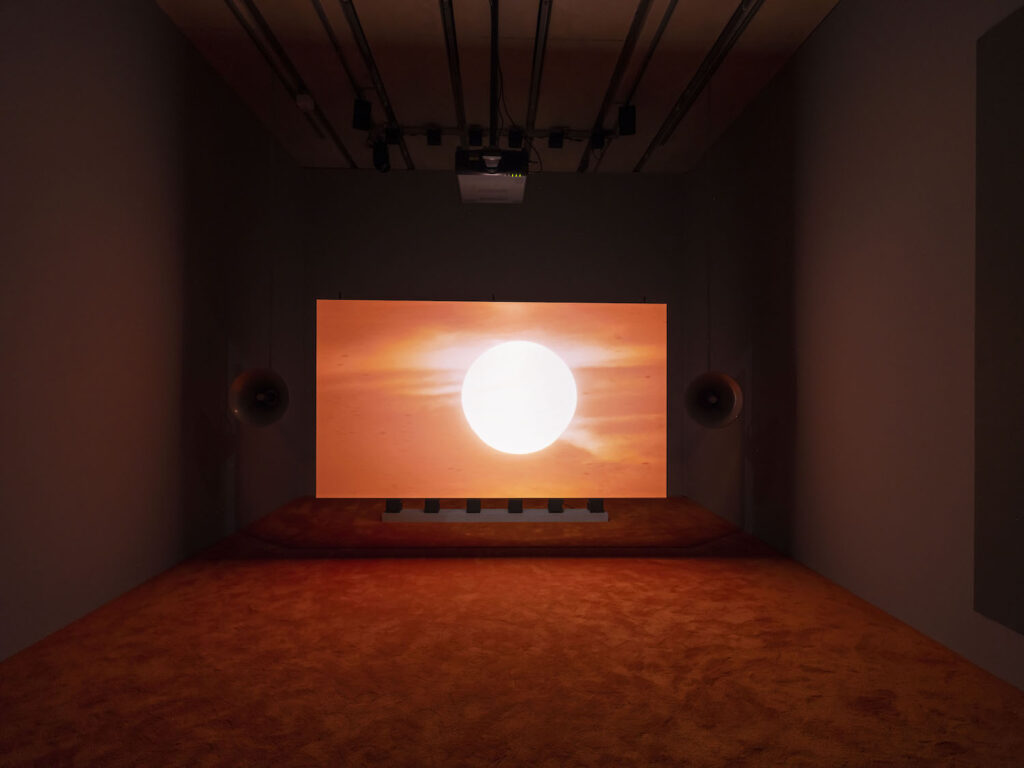

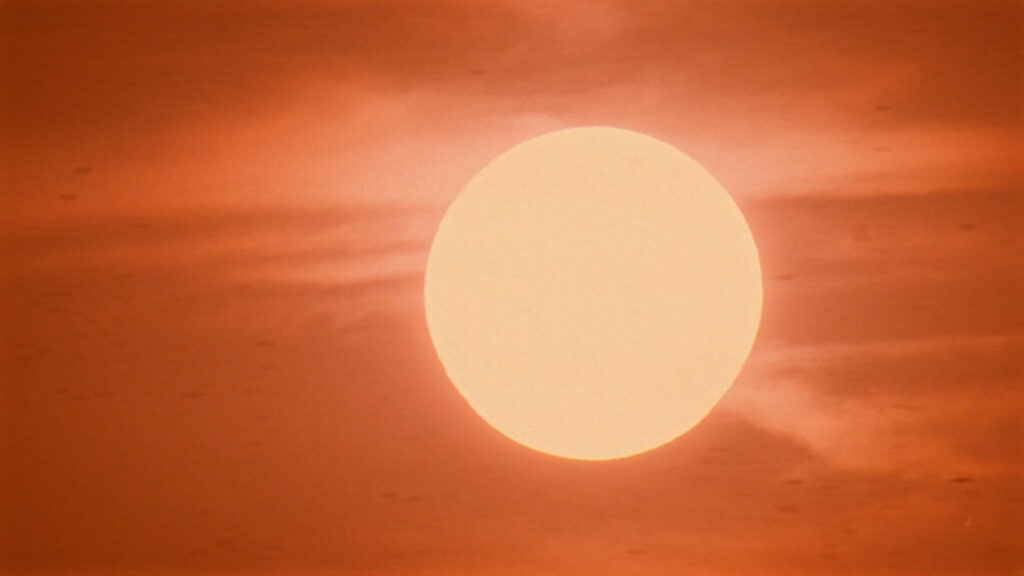

Not until I stay in the gallery to see the film restart from the beginning do I realize that Too Bright to See (Part I) opens on a landscape: iconic palm trees and smaller (perhaps) oaks, then shrubs and grass backlit by a rising sun, sky on fire. Until then, I had been immersed in words and images, voices and gestures. Cut to an orange rectangle with the sun, a sphere oddly small and pale for all its power, at the center, burning hot. Cut to French actress Zita Hanrot in sharp focus as Suzanne Roussi-Césaire, the shining literary sun too bright to see, I presume. Hanrot, herself a light that draws our gaze, brings into view a woman in thought, full of feeling, looking directly into the camera, addressing the viewer silently at first. Meanwhile, the atmospheric, incongruous, and enveloping sounds of birds and radio static pause, and we hear a brief thesis on the dual signification of the forest in Césaire’s writing. Cut to a truck arriving and, through a brief sequence, we are on the set of Too Bright to See, located in the Montgomery Botanical Center, a nonprofit institution designed for research and conservation of rare tropical plants.

What procedes from there feels akin to a series of imbricated dialogues between the director, Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, and Hanrot, between these two Black women artists and Roussi-Césaire; between South Florida and the forests of Martinique; between Roussi-Césaire’s words and the screenplay written by Hunt-Ehrlich and her collaborators. Too Bright to See carefully layers the processes of rehearsing and/as reflecting on Césaire’s writing. In this way, Hunt-Ehrlich seems to invite viewers to contend, as Césaire did, with “the great camouflage” of tropical nature, in which the paradisiacal idea of lush green beauty seduces the eye, hiding long histories of colonial exploitation, and to contend again with her own sumptuous filmic images and the lure of romantic narratives of historical biography, which she offers and resists, offers and questions.

Through her five-year research into the life and work of Suzanne Roussi-Césaire, Hunt-Ehrlich says she found “a great author without a body of work,” une grande auteure sans une oeuvre. Roussi-Césaire’s seven essays are nonetheless extraordinary and they are collected in The Great Camouflage, a monumentally important 2009 anthology that takes its title from an essay of hers published in the last issue of Tropiques, a journal she stewarded as editor and contributing author from 1941 to 1945. Her essay titles foreground her subjects: “Leo Frobenius and the Problem of Civilizations” (April 1941), “Alain and Esthetics” (July 1941), “André Breton, Poet” (October 1941), “Poetic Destitution” (January 1942), “The Malaise of a Civilization” (April 1942), “1943: Surrealism and Us” (October 1943), and “The Great Camouflage” (1945). Across these essays, anti-colonialist and feminist Roussi-Césaire examines philosophies of culture, identity, and politics through surrealism and art, sometimes in academic prose and, at others times, with urgent lyricism, all in her unique voice.

Hunt-Ehrlich is a filmmaker and visual artist trained in analog photography, which is evident in her detailed and crafted compositions in Too Bright to See. Her previous work, particularly Spit on the Broom (2019) and Conspiracy (2022), bears a contemplative almost haunting quality through the ways in which Hunt-Ehrlich weaves together archival material, narrative invention, and partially recovered cultural memory as she does in Too Bright to See. In this film, Hunt-Ehrlich brings her own imagination to Roussi-Césaire’s fragments, her passions, and her solitude.

In the conversation that follows, the artist and I discuss her realization, as shattering as it is fascinating, that there might have been more of Roussi-Césaire to read had she not, as her son claims, discarded her manuscripts. Within this bittersweet framework, Hunt-Ehrlich shares her creative process, particularly her collaborative approach, and her vision for the construction of the installation at Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) and how it might shape the audience’s aesthetic experiences of Césaire’s legacy. But the central impossibility or the mother wound or the big love of Too Bright to See feels like the desire to hear Césaire’s voice, the will to bear witness to the writing that the author herself discarded—writing that never was—to rest and to wrestle within the ambivalence of her creative possibility and to revel in her intellectual production, as a woman, as a Black woman of the Caribbean.

I edited our conversation for flow and clarity and to focus on Madeleine’s ideas and account of her process in creating Too Bright to See.

—Dr. Terri Francis

Terri Francis: I’m really excited to have this chance to get to know your vision and process for Too Bright To See, which I got to be on the set of, twice. That was so magical for me.

Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich: I felt like I had the most fabulous movie village in all of the film sets, in all of the lands, when I had Terri Francis, Simone Leigh, and Marina Magloire in my video village tent.

TF: Your project on Suzanne Césaire touches on so many areas of interest that we share—history, documentation, memory, and women’s artistry—though we engage them in different ways. How would you describe your practice? What was it like for you on set?

MHE: With Césaire, I was really working in between these disciplines of engaging seriously with archives, having parts of me that have these documentary sort of personal filmmaking sensibilities, but then also just really loving capital-C big cinema and production value. It was very fun and a celebration for me to have this big film set and the [opportunity to] focus on this poet from the 1940s. It’s a Black woman from the Caribbean, and her archive.

TF: Yeah! And I love the way you put that, that you’re working between disciplines. And I’m intrigued by the archival research part. I feel it has a kind of ephemeral presence in the film, but you could maybe explain a bit more.

MHE: Yes, so I would say, I had a layered approach. I spent five years in that process—and it had a multidisciplinary structure to it and so I visited archives. Suzanne Césaire doesn’t have an archive, but there are letters that she sent to famous French intellectual men—white men who do have archives that are well cared for and organized at major institutions like the national library of France. Basically, you go to the archives of half a dozen famous French male, white male intellectuals, and you find a letter from her. And I didn’t track down all of these letters. There are a lot—primarily because of Aimé Césaire—there’s been a lot of really important open-source scholarship done on him by many scholars that is invaluable. He has an archive, but it’s not . . . [voice trails off]. It’s also not totally as well organized as, say, André Breton’s papers. So . . . there’s been really great open-source work done around Aimé Césaire that really allows you to then pinpoint, “Okay, I need to go to Michel Leiris’s papers, or I need to go to René Étiemble’s papers.” You know, whatever it is. And you’re going to find a piece of her intellectual production there. And so I did that. I also recorded ten hours of interviews with her family, and that’s the part of me that’s from a documentary practice. I was being supported by and in conversation with scholars Anny-Dominique [Curtius] and Annette [Joseph-Gabriel], who were both publishing the work they’d been doing. 2 They were really helpful and supportive and generous. So, I think, similar to Anny’s process, there’s a kind of anticlimax in Suzanne Césaire’s particular story, because it really is one partially lost to time.

TF: What surprised you the most in your research?

MHE: For me, what was interesting was this idea that kept being repeated to me by her family, that you know, she didn’t want it. She wrote these essays, and then her political output, her intellectual output, took these other forms. The ways she was a teacher. The ways she was in her activism. The ways she was a mother. The ways she was in friendship. And it wasn’t about her as a writer—or as an artist. And her son says to me, which is in—we filmed this line being read—“Oh, well, she threw it away. She was always writing, but she would throw it away.” And it was worth sitting with the idea [of] is there agency in that choice?

TF: Writing something and throwing it away could’ve been a mode of protection. It could’ve been a feeling of defeat. “I’m no Aimé Césaire.” The rage behind saying that. I feel that. Yeah. It could’ve been self-destructive. It could’ve been some kind of agentive act too. I don’t know. That’s very, very complex.

MHE: But to say, okay, these essays are enough. Is there a different idea about what is worth historical memory? Is there resistance to or refusal of that? Or is it really just a reflection of the times, of the level of patriarchy we know still exists in the Caribbean [and] that is just profound? And that is partly why I set out to do the work.

TF: So if Suzanne Césaire throws out her writing . . . Did you see that as an ambiguous gesture with unclear meanings? Or did you feel that it definitely meant something?

MHE: Well, I thought it was an idea, that it was actually impossible to know the psychology [behind it]. There’s no part of me that thinks here’s [a piece of] information. This film is an information transfer. There’s no part of me that says, “We’re going to get to the bottom of this.” I mean, I think it was more that it was interesting to think about that [act] in relationship to the work itself, which was speaking really explosively about the ways Black people have lived and navigated the Tropics, which is itself an explosive site of really spectacular violence, and patriarchy, and racial capitalism, and—to throw that into relief—this idea of the ambivalence of the creative voice. That was what was interesting to me, and I wanted to think about it in an iterative way, basically because I relate to it. I relate to it as an artist—you know, where you’re always questioning your own voice—but also as a mother, as a Black woman whose heritage is of the Caribbean, of that space, of that level of claustrophobic patriarchy, you know? Where the women in that part of the family—it’s just left and right, your dreams are getting shut down, you know? But also knowing that there are these threads of intellectual production that are our heritage.

TF: You referred to Césaire’s letters as intellectual production, and I think that’s really important. You make an important gesture of honoring and elevating those documents that can easily float away. They were given away. You know, she sent them to people. It’s not a journal. It’s not a manuscript. It’s a letter to someone. And I think to regather, to gather those—when they’ve been scattered to all these other people’s collections—I think, is an important and caring gesture.

MHE: I think that the thing for me, and the thing for anyone who chooses to write a book or make a film or write an article about Suzanne Césaire, is . . . She was an incredible writer. She was exceptional, and she was very talented. So there was a mystery that was productive for me, which was how can you create something so beautiful and then say, “Okay, that’s enough.”

TF: Yeah.

MHE: And that was really interesting to me, and it felt like a good use of working with history, because it felt like a really evergreen question about creativity and the self that wasn’t just ending with her, but that had all these other implications—in my life and, I would hope, in other people’s lives, in other women’s lives.

TF: You spoke of your village earlier and the importance of collaboration. Could you talk about your work process with the actress who plays Césaire (and I think you as well in a way), Zita Hanrot.

MHE: With Zita, who has a really beautiful preparation process, we were doing a lot of almost daily meetings and readings of the text, and that really found its way into the film. It was always sort of written into the text that there was going to be this reading process and this awareness of the archival material through pages [pause]. With Zita, I was writing parts of the script as we were rehearsing and reading together. We had gone really into this place where text was being generated from reading Suzanne together, as women sharing an experience and an exhaustion that we shared with Suzanne, too.

Courtesy of the artist.

TF: And Marina?

MHE: Marina and I wrote some texts together . . . [including] a speech that we cowrote, and it’s partly based on research Marina did about what was happening during [World War II]. The speech is in the film at PAMM.

TF: And that goes to form. How do your ideas about form manifest in the installation?

MHE: So, with the installation, I’m really interested in this idea that filmmakers working outside of the commercial film space reimagine distribution. But I truly feel that we’re maybe even called now to reimagine the theatrical contract with our audience as the theater becomes increasingly obsolete.

TF: How so?

MHE: People leave their expectations of what the contract is between audience and artwork at the door, and they’re really open to different ways of experiencing something. So for me, it’s about what it is that I want my audience to see. And sometimes it’s the film, but sometimes it’s not the film. It’s something I want to point them to, that’s internal for them, and my question is how do you do that using space? Not just what is in the film itself. How do you create space in the unfolding of time, of the experience for that?

TF: So there’s an experiential component?

MHE: I am comfortable feeling bored during films. I do some of my best thinking about other things during films. And so I have a real strong belief that, you know, the audience is allowed to separate from the film and then go back to it, and . . . I think that’s really kind of noncommercial [both laugh].

TF: Very much so. The screen in Too Bright to See is unusual. Could you explain how it came to be?

MHE: For the installation, the idea was to work with a scrim that could move between a cinematic experience and one where projected light almost passes through. And for this iteration of the film, we were thinking a lot about the experience of the tropics, and [pauses] the real beating sun that you can experience [pauses]. And part of that was this idea I had about trying to make sense of the difference between Aimé Césaire’s work, Suzanne Césaire’s contemporaries’ and friends’ and colleagues’ work, and her own work—her small output. And to think about it like there’s the sun, there’s a big strong light that fills the space, and then there’s also, you know, the lantern, which is another form of light and attention, but it’s one that’s also moving [pauses]. In the daytime, it’s not something you see.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

TF: You’re making me think of the old-time kerosene lamps . . . Sorry, go on.

MHE: Yeah. Absolutely. I mean so much of the rhythm of a Caribbean day actually is that people really come out and have a lot of their life experience after the sun is down or [pauses] when it’s cool enough to be together or to meet a beau or to sit on the porch and actually speak to your neighbors, so . . . These were some of the moments that we were working through. It was actually really hard to pull off a scrim that would give you a true cinematic experience and then could go transparent. There’s a contradiction in terms of how material works and how projection works. A material is either really transparent and has that ability to have that beautiful quality of feeling like gauze or another material that you can really see through. Or material holds and sucks in light very well. And so the way that we finally solved that was [through] a combination of two transparent materials that are separated by a frame, and by making the angle of the projection really, really steep so that the projection hits the fibers at enough of an angle that light isn’t being lost through the weave of the fabric.

MHE: And . . . you know, the idea that the film itself might disappear from the experience or be sort of . . . that you would have that effect of the film sort of disappearing in a way that really emphasized something that you can’t grasp. That was how I felt about Suzanne Césaire the whole time I was working towards her. I’m thinking about the chapels where I want people to encounter the work, because really, it’s about the way I like to encounter work, too, you know?

TF: Can you say more about that? It’s so fascinating how filmmakers watch films.

MHE: Well, and this sort of goes to the form of the film itself, which is that for me, slowness—slowness of scenes, slowness of performance, slowness of the shot—is really important and is political for me in that, again, I think about actually encouraging an audience to disconnect from the work. And also understanding for me that so much of what I’m thinking about in an edit is about what the pacing of the footage is doing to my body, and about this understanding that when we’re bored, we actually become more aware of our bodies, . . . When we’re uncomfortable, we become more aware. When we’re bored, we become more aware. And that’s something that we can only tolerate for these weird intervals, you know?

Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

TF: Interesting!

MHE: People can get really angry. They’re like, “This is boring,” or “that was boring,” or . . . You know, people get mad at movies all the time [laughs].

TF: You welcome this?

MHE: Well, I guess I’m chasing some kind of perfect . . . some kind of perfect pace, where you can slip [away] and then that’s where my pleasure, my commitment to pleasure, also comes in, because there are filmmakers who are way more . . . well, I call it anti-pleasure. I actually am not anti-pleasure or [against] the trappings of cinema, the romance of it, at all. I just also really enjoy this thing that happens to you in experimental film, where you get to be with your gut or with the room itself.

TF: Let’s go back to this idea of boredom as an aspect of the work. The slipping away. Because that seems linked to this other connection between Césaire as an author who disappears and this film as a film that can disappear—and from which the audience can disappear and reappear. And that there’s something for you, there’s something in the art space, in the gallery space, and then the installation that allows this to happen.

MHE: A lot of times when I’m looking at work, I’m not—I’m looking at film, but I’m also looking at sculpture, or I’m looking at painting [pause] or I’m thinking about music.

TF: You’re thinking through space in two ways: The physical space of the gallery and the mental or intellectual or emotional space of viewing, or within viewing. It’s not only about getting sucked into the work. It’s that there’s still space between the viewer and the film. It’s an object. It’s not a vacuum into which the viewer goes.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

MHE: And first, in the gallery context, the film is always reedited by the body coming into the space.

TF: The gallery space lets people come in and out. You’re there. There are other people. Maybe you come in at the five-minute mark, and then you’re going to stay and watch it like I did. Other viewers continue to come into the room. So it’s a different viewing experience from the theater, which begins and ends at a certain time, and you’re supposed to sit there and not talk, and the whole room points you towards the screen.

MHE: Another thing that’s very strange about the film space versus the art space is this idea that when people go to see films, they [pause] expect the filmmaker to have a conversation afterwards.

TF: Okay. Please say more.

MHE: I don’t need to understand.

TF: I guess I have two questions about that. One of them is a three-part question [laughs].

MHE: Okay.

TF: That’s very Q and A–ish, as though we were having a conversation after seeing your installation. I wonder how you’re viewing this piece as being part of the catalogue accompanying Too Bright to See. What do you want to convey to our readers, and how do you see the catalogue functioning with—or against—the installation?

MHE: So, you know, the work on Suzanne Césaire is really a body of work, and it’s taken these many forms. The installations are informed by the idea of light, and light is something that’s a really central, formal material of cinema. It has all these metaphorical properties, too. And so, you know, we’re talking about Suzanne Césaire—this writer who barely has any writing for us to study—in these various degrees and gradations of light and exposure and clarity. And the work will live in these installation forms and, ultimately, it will also live as a film. What Suzanne’s given me is time to think about the fragment as a form, and also to think in defense of a fragment as a feminist form that is actually more connected to [. . .] the rhythms of women’s lives, of our social lives, of our output, [of] our creative output, [of] our private output. The ways we’re constantly having to juggle many things to survive in the way society’s set itself up for us. Suzanne Césaire left us fragments, and I feel myself existing in fragments, and I think I’m just adding a fragment to whatever she’s left behind. Hopefully there are more people who have more to say. But I’m really content with those pieces, and I’m not trying to fix that.

TF: That actually answers the question that’s been on my mind, which is how you will or how you are handling that desire on the part of some viewers to have you fix it or fill in the gap in our knowledge.

MHE: Abstraction to me serves some political function as an alternative way to see and feel, to learn and to know. The question gives us the thing itself. When I was working with the lead actress, with Zita, we talked about how, okay, you’ll come away from this work with the feeling of her, but maybe not with all the dates and facts. But I think the feeling will live with you longer. And I really think that [. . .] it’s our job as makers to nurture a kind of mystery that’s a stronger [. . . ] aesthetic experience than . . . The delivery of information is really important. I just don’t know if that’s, for me, the best use of the cinematic experience.

MHE: And you know, I don’t think I’m doing it alone. I view myself as a part of a constellation of people working on a particular history. And that could be in many forms. We could say, a constellation of people working on Suzanne Césaire. We could also say a constellation of people working on what she was working on, which are these ideas of a very kind of temporal engagement with living itself, or surviving . . . surviving the violence of the world. And you know, I don’t—that’s part of, I think, the defense of the fragment is it’s . . . The burden of completion isn’t actually on any one of us, and that value is a really misguided value, you know?

TF: Yeah, I hear that. And as you were talking, I was thinking, “Yeah, this is the defense of the fragment,” and you went right there. I guess we—we don’t have too much more time. I never asked you about location and how you—I mean, I think I know a little bit about the logistics of how you eventually landed on [filming in] South Florida, but I think when we watch the film, we’re not supposed to think of it as South Florida or Coconut Grove, specifically. But it’s also not quite Martinique either. It’s a surreal space. It’s a landscape, or a backdrop. You chose this palm-filled backdrop for the playing out of your engagement with Césaire’s work. I mean, does that sound close to . . . ?

Courtesy of the artist.

MHE: There’s a couple layers to it. I really found the form through Sarah Maldoror’s film, one of her Césaire films—Le masque des mots.

TF: Yeah. The Mask of Words.

MHE: Yeah. And the scene with Maya Angelou in the Everglades in the lawn chair reading. [TF nods in recognition.] Yeah. Maya Angelou reading in her Southern French, that kind of linkage, so I thought “Oh, the film is this scene.”

TF: Yeah.

MHE: And actually, Suzanne Césaire, in [The Great Camouflage] talks about the Americas in this way where she’s standing on a piece of land in that way, where she’s [pause] thinking about the multiplicities of this land, and this experience, with different colonial textures. The other piece of it was that we were really lucky to find a tree archive in South Florida. I mean, South Florida has been not only gentrified, but just developed within an inch of its earth, and we found this really well-kept secret—in the middle of Coconut Grove, essentially—this tree archive. And the idea of what histories are preserved here in this archive, I think, was really perfect for the work, and it also just provided such a meditative contained space for us to walk and read, which is an act that has to be sort of protected to exist.

MHE: I think it was Daniel Maximin, one of her first biographers, who said, you know, if you want to understand Suzanne Césaire, go to the forest. Her children said that, too, because she was very fond of walking, and they always made sure to live by a forest. Even when they lived in Paris, they lived outside of the city in Petit-Clamart and right across the street from the big forest. That was something that was a part of her, to go on walks alone.

MHE: And so this idea that when we’re searching for her, this is where we’ll find her, was one of the ways I . . . If there’s anything investigative about the work, it was that some of the answers were from the archives or from people who knew her, and some of them were from going to the places you know that, internally, she did, too.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich is a filmmaker and artist who has completed projects in Kingston, Jamaica, Miami, Florida, and extensively in the five boroughs of New York City. Her work has been screened all over the world including at the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival, 2022 La Biennale di Venezia, the Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum of Art in New York, and the Tate Modern in London. Her films have been awarded special jury prize for best experimental film at Blackstar Film Festival and New Orleans Film Festival. She was named on Filmmaker Magazine’s 2020 “25 New Faces of Independent Cinema List” and is the recipient of a 2022 Creative Capital Award, a 2020 San Francisco Film Society Rainin Grant, a 2019 Rema Hort Mann Award, and a 2014 Princess Grace Award in film.

- Césaire, Suzanne, The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941–1945), ed. Daniel Maximin, trans. Keith L. Walker (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2012), 64. This edition is a translation of the 2009 volume produced in French by Sueil.

- See Anny-Dominique Curtius, Suzanne Césaire. Archéologie littéraire et artistique d’une mémoire empêchée [Suzanne Césaire: Literary and Artistic Archeology of a Hindered Memory] (Paris: Karthala, 2020); and Annette Joseph-Gabriel, Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire, The New Black Studies Series (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2020).