Art collections are revealing cultural artifacts beyond the sum total of the individual works of art within them. They reflect cultural and artistic canons; ideas about art and culture; and particular interests, tastes, and personalities. They also produce such values and can, as we will see in this essay, be mobilized to challenge them, either actively or passively. Major art collections are historical documents that reflect the social dynamics of the societies in which they are located and, while moderated by their association with wealth and power, also reflect how cultural identity is constructed, which is important in a postcolonial context.

Jamaica offers an interesting case study of art collecting in the Caribbean. During the colonial era, Jamaica served as a source of natural and ethnographic specimens in pioneering extractive collecting and natural history practices that helped to shape the modern museum. The Institute of Jamaica (IOJ) was established in 1879 as the first locally based collecting institution, for “the encouragement of literature, science, and art in Jamaica,”1 according to its mandate, but did so from a late colonial perspective, with a view toward asserting the beneficial nature of the British Empire and positioning Jamaica as an attractive location for investment and white migration. It was one of several such institutions established in the British Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.2

As nationalist, anti-colonial sentiment took an organized form in the 1930s, accompanied by the emergence of a nationalist school of art, it was inevitable that the focus of the IOJ’s collection would be challenged: In a much-publicized incident, the IOJ’s management was heckled at the 1936 annual general meeting by members of the nationalist intelligentsia, who demanded that its portrait gallery, which featured mainly colonial figures, be torn down and replaced with a gallery devoted to modern Jamaican art.3 The first modern Jamaican work of art to enter the IOJ collection, Edna Manley’s iconic sculpture Negro Aroused (1935), was acquired in 1937 by means of a public subscription supported by the nationalist intelligentsia.4 Carved from mahogany in a style related to Art Deco and Cubism, Negro Aroused celebrates the political awakening of the black Jamaican masses, which had found expression in Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association, early Rastafarianism, and the labor unrest that swept through the Anglophone Caribbean in the 1937–38 period.

The nationalist art movement was, however, fraught with social contradictions: While blackness and aspects of the popular culture were adopted as the default national cultural identity, most of the movement’s patrons belonged to the light-skinned local elite. This included Edna Manley (b. 1900, Bournemouth, Hampshire, England; d. 1987, Kingston, Jamaica), who was born to an English father and Jamaican mother, and her husband, the lawyer and nationalist politician Norman Manley. These tensions had significant implications for how nationalist cultural interventions were interpreted as Jamaica moved toward independence.5

I. Art Collecting in the Post-Independence Years

The first major private and corporate collections in Jamaica appeared after the country gained independence in 1962. These included the holdings of private collector A. D. Scott (b. 1912, Kingston, Jamaica; d. 2004) and those of the Bank of Jamaica, the central bank. The National Gallery of Jamaica (NGJ) was established in that same general context.

Collecting was at that time positioned as a progressive, nation-building, and philanthropic practice, one that supported artists as well as public cultural interests. Moreover, it coincided with the emergence of a black professional class that provided an alternative to the patronage dynamics of the nationalist movement. A. D. Scott was the first black art collector of note in a context that still exists today, in which most collectors are light-skinned members of the traditional upper classes. Younger Jamaican artists, such as Barrington Watson (b. 1931, Lucea, Jamaica; d. 2016, Kingston), Eugene Hyde (b. 1931, Cooper’s Hill, Portland, Jamaica; d. 1980, St. Catherine), and Karl Parboosingh (b. 1923, Saint Mary, Jamaica; d. 1975), who founded the Contemporary Jamaican Artists Association (CJAA; 1964–74), challenged the restrictive tenets of the nationalist art movement and advocated instead for an internationalist modernist outlook in which they were seen as artists first, and specifically black artists, and Jamaican artists second. Watson, who was a vocal exponent, in particular challenged the dominance of Edna Manley and her circle, while attracting the enthusiastic patronage of the new business classes.

Tourism was another factor in the development of modern collecting in Jamaica. As mass tourism became the norm, Jamaica had to assert its cultural distinctiveness in the genericizing but increasingly competitive tropical destination field. In what was an innovative strategy to prove that Jamaica was “more than a beach,” artists such as Revivalist bishop and self-taught artist Mallica “Kapo” Reynolds (b. 1911, St. Catherine, Jamaica; d. 1989) were featured in Jamaica Tourist Board advertisements. Several hotels also started collecting Jamaican art. These included the Stony Hill Hotel, a small hotel in the hills above Kingston, whose American owner, Larry Wirth, acquired a substantial collection of paintings and sculptures by Kapo. This collection was bought by the Jamaican government for the NGJ in 1983 and forms the core of the Mallica “Kapo” Reynolds Gallery, one of two galleries dedicated to major artists—the Edna Manley Galleries being the other. Hotelier John Pringle, who was Jamaica’s first director of tourism and played an important role in the Jamaica Tourist Board advertising campaigns, was also an avid collector of Kapo’s paintings, and part of his private collection was donated to the NGJ in 2011.

Michael Manley, Edna and Norman Manley’s son, became prime minister in 1972 and took Jamaica down a democratic socialist path, while forging alliances with Cuba and other countries in the Non-Aligned Movement. This shift negatively affected Jamaica’s economic stability and, in the late 1970s, led to paralyzing political violence with alleged CIA and Cuban involvement. The 1970s were nonetheless a period of significant cultural growth in Jamaica, with reggae music its most influential product. Several cultural institutions were also established during this time, including the NGJ in 1974 and the Cultural Training Centre, now the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts, in 1976.6

The National Gallery of Jamaica

The NGJ was established in a politically progressive context, but its initial mandate was narrow and conservative. The NGJ inherited about two hundred modern Jamaican paintings and thirty sculptures from the IOJ collection, while ceramics remained at the IOJ and historical prints were transferred to the National Library of Jamaica. “Art” was thus exclusively defined as painting and sculpture. The articles of association furthermore mandated the NGJ to collect and exhibit the art that came out of the nationalist uprising of 1938, thus essentially conflating “Jamaican art” with the nationalist school.

These narrow definitions were quickly challenged by David Boxer (b. 1946, St. Andrew, Jamaica; d. 2017, Kingston) when he joined the staff as director/curator in 1975.7 Boxer had obtained his Ph.D. in art history at Johns Hopkins University and was a protégé of Edna Manley. He was also an artist, private collector, appraiser, and advisor to private collectors. Because of these combined roles, his foundational part in the articulation of Jamaica’s art-historical narratives, and the formidable social and political connections he cultivated, Boxer quickly became the most powerful figure in the history of Jamaican art.

Through exhibitions such as Five Centuries of Art in Jamaica (1976), Boxer articulated a longer and broader view of Jamaican art history, one that began in the precolonial era and included a much wider range of genres and mediums. This was articulated along the lines of a conventional art historical survey, although still asserted that “true Jamaican art” was the product of modern anti-colonial nationalism. The scope of the NGJ collections was widened accordingly, and in 1976, for instance, the NGJ received an additional sixty works from the IOJ’s colonial collections.8

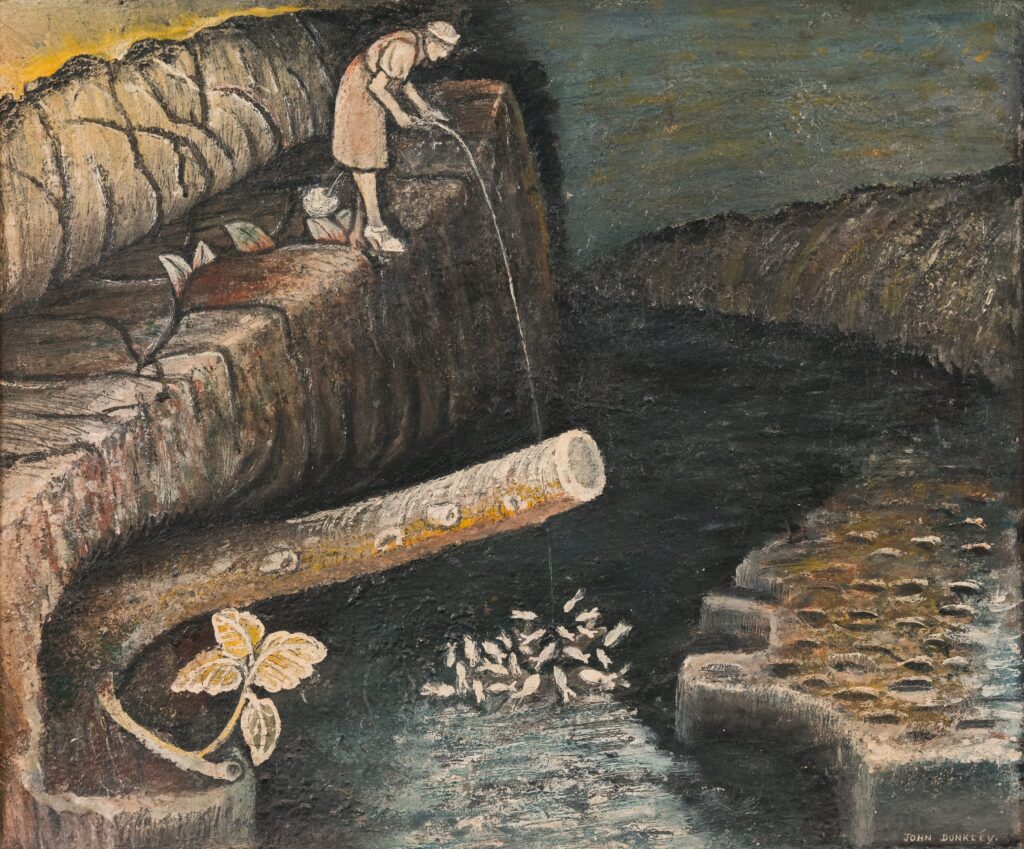

Another key aspect of Boxer’s rearticulation of Jamaican art history was the concept of “Intuitive” art, which he introduced as an alternative to more obviously problematic concepts such as “primitive” or “naïve” art.9 Boxer’s intervention went beyond coining a more palatable term: The IOJ collection already included work by key exponents such as John Dunkley (b. 1891, Savanna la Mar, Jamaica; d. 1947, Kingston), Kapo, and Everald Brown (b. 1917, St. Ann, Jamaica; d. 2003, Brooklyn, New York), but Boxer radically repositioned these artists, moving them from the margins to the center of Jamaican art history. This shift was asserted in exhibitions such as Intuitive Eye (1979) and the survey Jamaican Art, 1922–1982,10 and supported by the acquisitions program.

The NGJ, which falls under the umbrella of the IOJ, receives its operational funding from the Jamaican government, but this barely covers salaries and overhead. Capital funding is only rarely allocated and does not normally include funding for acquisitions—the State support of the Larry Wirth Collection acquisition remains a rare exception. Most acquisitions are funded through other sources, including sponsorship, grants, income-earning activities such as admissions and the gift shop, and occasional fundraisers.11 There has consequently been a high reliance on donations in the development of the NGJ collection, of individual works and entire collections from artists and collector-patrons alike. While this practice has allowed the collection to grow by leaps and bounds, it has also worked against developing it in a well-planned, strategic manner.

The first major donations were the A. D. Scott Collection, which is discussed below, and the Edna Manley Memorial Collection. The latter involved a campaign, spearheaded by the new NGJ chairman Aaron Matalon (an influential businessman and arts patron who also chaired the Edna Manley Foundation), to convince private and corporate collectors to donate major Edna Manley works to the NGJ. This successful campaign, started shortly after Edna Manley’s death in 1987, has yielded a representative body of Edna Manley’s work, with key works including Horse of the Morning (1943), which was donated by Michael Manley. This collection, along with other works by Edna Manley owned by the NGJ or on permanent loan, are now on permanent view in the Edna Manley Galleries.

The Edna Manley Memorial Collection was not the only donation spearheaded by Matalon. His own major donation, the Aaron and Marjorie Matalon Collection, was handed over to the NGJ in 1999 and consists of some 230 works, including a unique collection of historical maps and prints, as well as modern and contemporary works. It was an unusual donation, as most of it did not come from the Matalons’ personal holdings but rather was specifically acquired, in dialogue with Boxer, to address gaps in in the NGJ collection. The gift came at a time when the NGJ was under fire from artists who questioned its representational politics, and included work by the institution’s most vocal critics, among them, Roberta Stoddart (b. 1963, Jamaica), Judy-Ann MacMillan (b. 1945, Kingston, Jamaica), and Barrington Watson (b. 1931, Lucea, Jamaica; d. 2016, Kingston). Several other donations and acquisitions had similar diplomatic agendas: The Larry Wirth Collection acquisition, for instance, was spearheaded by Edward Seaga, then prime minister and an early patron of Kapo, and provided a political and artistic counterpoint to the Manley-centeredness of the early NGJ, while adding substance to its Intuitives holdings.

This reliance on donations does not mean that the NGJ’s own acquisitions have been inconsequential. In fact, some of these acquisitions have challenged the collection’s canonical boundaries more radically than the adjustments made by certain donations, as the decisions were made by the curatorial staff, and not moderated by the tastes and agendas of patrons. The acquisition of A Cultural Object (1985) by Dawn Scott (b. 1951, Mandeville, Jamaica; d. 2010), for instance, widened the scope of the collection with a seminal work that challenges conventional ideas about art and Jamaican culture. A room-size installation made from recycled building materials and covered in graffiti, A Cultural Object was produced for the NGJ’s first exhibition of installation art, Six Options: Gallery Spaces Transformed (1985). Scott’s installation inserts a visceral, immersive re-creation of Jamaica’s inner-city life into the space of an institution conventionally associated with social privilege and rarefied ideas about art, and is thus a powerful institutional critique. A Cultural Object is presently closed for conservation, but it is one of the most popular art works at the NGJ and has been a significant influence on younger artists.

Today, the NGJ collection consists of approximately 2,500 works of art, spanning from the precolonial to the contemporary, and in a diverse range of mediums, techniques, and styles (now including digital and time-based media). There are a few lingering gaps, but its scope as a collection of Jamaican art, with some international, mostly Caribbean holdings, is encyclopedic. It is, despite the canonical disputes that have shaped it, the collection of reference for Jamaican art history, holding many of the defining examples of historical, modern, and contemporary Jamaican art.

The Bank of Jamaica Collection

The BOJ had already acquired a few works of art in the 1960s and early ’70s but decided to acquire a major collection for its new, high-rise headquarters, which opened on the Kingston waterfront in 1975. Barrington Watson was invited to chair the acquisitions committee, which also included the artists Karl Craig (b. 1937, Jamaica), Eugene Hyde, and Melvyn Ettrick (b. Jamaica)—all influential figures in the Jamaican art world at that time. The acquisitions included several commissions for the new building.

The efforts of the committee were controversial as its members were accused of promoting their own work while excluding other established artists, including Edna Manley. Indeed, Watson was the main beneficiary of the early BOJ commissions.12 He received the two main commissions: A large environmental work titled Trust (1975), which was executed with ceramist Cecil Baugh (b. 1908, Portland Parish, Jamaica; d. 2005) for the banking hall, and a large mural titled The Garden Party (1976), which was executed in the foyer of the BOJ auditorium.

The conflict of interest is obvious—and parallels similar conflicts faced by Boxer—but Watson may have felt that the BOJ collection amounted to a necessary counterpoint to the art historical hierarchies that were being put forward by the NGJ. Such views are not unjustified. When the NGJ was established, the transfers from the IOJ did not include any of Watson’s works, although he was already a well-established artist. It took until the late 1970s before a major work by him, Mother and Child (1958), finally made it into the NGJ collection, by means of an unsolicited donation.13

Despite the contentions, the BOJ’s original acquisitions are among its most important, as they represent a pivotal moment in Jamaican art and culture. The Garden Party, for instance,is a satirical portrayal of the foibles of Jamaican society in the turbulent 1970s. Staged in an idyllic tropical landscape, there are at least fifteen distinct vignettes of Jamaican life, some of them realistic, such as the worshipping Revivalists, and a few others metaphorical—the key scene, for example, is a boxing match between Michael Manley and Edward Seaga. The Garden Party was painted during the momentous year in which Manley declared a state of emergency, motivated by rumors that the Seaga-led opposition was plotting to overthrow his government. It may seem surprising that such a political work was acquired by Jamaica’s central bank during this volatile political moment, but the BOJ was more open to provocative form and content than other corporate collections in Jamaica. That some of the leading artists of the time directed the foundational acquisitions may have contributed to this liberal outlook.

Around 2000, an active effort was made to bring the collection up to date with new acquisitions from contemporary artists such as Hope Brooks (b. 1944, Kingston, Jamaica), Roberta Stoddart, Petrona Morrison (b. 1954, Manchester, Jamaica), Laura Facey (b. 1954, Kingston, Jamaica), and Omari S. Ra (b. 1960, Kingston, Jamaica), and Edna Manley is now represented with a small posthumous bronze. The BOJ collection is one of the most significant and best kept art collections in Jamaica. Key works can be seen by the public in the entrance lobby, banking hall, and auditorium.14

The A. D. Scott Collection

The Jamaican collector A. D. Scott was a structural engineer who participated in iconic public construction projects around Jamaican independence in 1962, such as Kingston Airport and the National Stadium. Scott was one of the founders of the CJAA, along with Watson, Hyde and Parboosingh, and their work represents the bulk of the collection, but Scott also collected work by other artistic contemporaries. This included Edna Manley and other artists of the nationalist school, a few Intuitives, and regular Caribbean visitors such as Aubrey Williams (b. 1926, Georgetown, Guyana; d. 1990, London, England) and Erwin de Vries (b. 1926, Paramaribo, Suriname; d. 2018, Paramaribo), both of who were associated with the CJAA.

In 1974, Scott opened the Olympia International Art Centre, an apartment-and-hotel complex and art gallery located near the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus in the suburbs of Kingston. The complex housed much of Scott’s rapidly growing collection and mural commissions, such as Our Heritage (1974) by Barrington Watson, which circles the inside of the top floor of the apartment block. Olympia also staged regular exhibitions, including the Caribbean Women’s Art Exhibition (1975), which was the first exhibition of work by women artists in Jamaica. The concept was to integrate art, tourism, education, and residential life, and at least one apartment was reserved for an artist in residence: Karl Parboosingh, who lived there during the final year of his life.

Olympia opened the same year as the NGJ and was another implied acknowledgment of the need for alternatives, in this case as a private initiative. Scott’s collection told the story of art in Jamaica in the years after independence from the point of view of an opinionated insider. Unlike Watson, who was a vocal critic, Scott maintained a cordial relationship with the NGJ. My first exhibition for the NGJ, which was co-curated with David Boxer in 1988, featured selections from the A. D. Scott Collection. Most of the works in that exhibition were donated to the NGJ in 1989, in what was the first donation of such magnitude in Jamaica, and selections are now on permanent view in the NGJ’s modern galleries. Other parts of the collection subsequently went to the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus and the University of Technology.

A few works, such as the murals, remain in Olympia, although some are in poor condition due to water leaks, termite infestations (which are common in Jamaican buildings), and the lack of climate control. The central hall still serves as a commercial gallery, with an adjacent framing and art supply store. It may not be the ambitious international art center Scott had in mind, but Olympia still contributes to the local art ecology. It is presently the only large, private exhibition space in Jamaica, which has made it a popular venue for contemporary artists.

II. Art Collecting in Neoliberal Jamaica

The violent general elections in 1980 brought the Edward Seaga–led Jamaica Labour Party to power and put Jamaica on a more conservative, economically neoliberal path, while putting the country back into the good graces of the United States. Art collecting became a fashionable, high-status activity for the professional class, with the idea of collecting as a form of investment taking hold. The 1980s and ’90s were also a pivotal moment for the development of contemporary art, in which emerging artists such as Milton George (b. 1939, Manchester, Jamaica; d. 2008), Omari S. Ra, Dawn Scott, Petrona Morrison, Charles Campbell (b. 1970, Jamaica), and David Boxer himself challenged conventional art definitions and values in Jamaican art, and introduced new mediums and formats, including installation art. Predictably, however, the market primarily supported those artists whose production conformed to the conventional, tradable art object, and locally, there has been little patronage of the more radical forms of contemporary art.

The NGJ had a major impact on collecting in Jamaica and several private collections evolved in its periphery. Boxer liked to invoke William S. Lieberman’s alleged statement, “I don’t collect paintings, I collect collectors,” as his guiding philosophy.15 He actively courted local and international collectors of Jamaican art, and most of the donations the NGJ received during his tenure resulted from those relationships. He also served as de facto advisor to several private collectors, with his wide-ranging connoisseurship and privileged access to artists and the resale market. This included his friend and NGJ Board of Directors member Wallace Campbell, whose collection rapidly developed into one of the most significant in the Caribbean. Boxer was himself a major collector.

There were many in the Jamaican art world, including Barrington Watson and later on, the Indian expatriate critic Annie Paul, who felt that Boxer was overstepping his professional boundaries not only by advising collectors but also, even more so, with his collecting, appraisal, and art-selling activities—and his frequent and prominent inclusion, as an artist, in NGJ exhibitions.16 The question indeed arises whether his overlapping functions in the Jamaican art world represented a conflict of interest and thus were inappropriate for a museum professional and civil servant.17

The David Boxer Collection

David Boxer was an adventurous and inquisitive collector who was not afraid to buy work from young or unknown artists, along with the big names in Jamaican art. While best known for his Intuitive holdings, Boxer maintained a collection that was eclectic and wide-ranging, and covered the breadth of Jamaican art. He also collected early Jamaican and Caribbean photography, stamps, antiques, design, and popular furniture; original archival material relevant to Jamaican art; Taíno and African art; and many other items of cultural interest, most of them related to Jamaica. The size of Boxer’s art collection is unknown as there were continuous sales and new acquisitions, but at its peak, it must have numbered in the thousands, including major examples of his own work.

Boxer lived in a 1920s hacienda-style mansion that was of historical and architectural significance—and which he expanded with an annex that housed his substantial art library and several gallery and studio spaces.18 He actively lived with his collection, in what was an ever-changing staged environment that came close to the large, multipart installations he produced as an artist; indeed, his curatorial, artistic, and collecting practices were inextricably intertwined. His John Dunkley paintings and sculptures were, for instance, exhibited in a special room in which he also displayed curios and antique popular furniture in a veritable cabinet of curiosities that resonated aesthetically and culturally with Dunkley’s work.

Boxer regularly organized sales exhibitions at his home, of his own work and occasionally that of other artists, and he willingly entertained visitors and researchers who asked to view his collection. Further, his house and collection were regularly featured in industry periodicals such as Art & Antiques and Art & Auction.19 He also lent work to many NGJ exhibitions but was credited anonymously in such instances. Boxer often spoke about turning his home into a permanent private museum and established the Onyx Foundation to this end, but it appears that this effort was not backed up with a sustainable business plan.

The Wallace Campbell Collection

Wallace Campbell was an affluent Jamaican businessman who started collecting in the late 1970s. By the end of his life, his collection comprised approximately 1,500 works of art, mostly paintings, sculptures, and works on paper from Jamaica, Cuba, and to a lesser extent, Haiti—and was one of the most ambitious private art collections in the Caribbean.20 While he also acquired art locally, he was also a regular customer of major international galleries and auction houses such as Christie’s, as well as patronized Cuba’s government-controlled art market.

Wallace Campbell’s focus was on the modern and colonial period, and he also owned Taíno artifacts. Unlike Boxer, Campbell only acquired work by established artists, with a preference for the canonical “masterpiece.” In his more conservative, risk-averse view of art, there was little or no room for contemporary art, especially if it departed from conventional notions about the “art object.” He was, however, quite comfortable with modernist works dealing with challenging subjects and, for instance, collected several works that were critical of Jamaica’s political history.

One of these was Eugene Hyde’s iconic painting Behind the Red Fence (1978), which is part of the artist’s Casualties series. In the Casualties, Hyde combined abstract political color symbolism with figurative elements, and painting and drawing mediums: The paintings are populated by ghostly, bandaged figures inspired by the growing number of ragged, anonymous homeless people increasingly present on the streets of Kingston and, in Hyde’s view, symbolic of the deprivation faced by the Jamaican people during the turbulent 1970s. In Behind the Red Fence, such a figure is partially concealed by a frayed but blood-red sheet of “zinc,” or corrugated metal, one of the main recuperated building materials used in Jamaica’s urban slums. The red refers to communism and the bloodshed in Jamaica, thus symbolically linking the two—Hyde was an outspoken critic of the Manley government. The painting now belongs to Carlyle Farrell, a Trinidadian economist, academic, and Caribbean art collector who lives in the greater Toronto area.

Campbell also owned furniture by Jamaican Art Deco designer Burnett Webster (b. 1902, Cayman Islands; d. 1992) and bought the latter’s iconic 1930s home on Seaview Avenue in Kingston to house his own collection when his residence became too small. Webster’s house was built in a hacienda style comparable to Boxer’s but with stunning Art Deco woodwork designed by Webster himself and executed by Jamaican sculptor Alvin Marriott (b. 1902, Essex Hall, St. Andrew, Jamaica; d. 1992). Like Boxer, who encouraged him to do so, Campbell toyed with the idea of a private museum, and though he probably had the means to endow such a venture, it did not materialize. Nonetheless, for several years, he operated the Seaview Fine Art Gallery at his premises, where many well-attended exhibitions and art functions were held, as well as readily accommodated requests from researchers and curators to view his collection, or to lend to exhibitions.

Both men have now died, and their collections have largely been dispersed, although it appears that some of Boxer’s collection has been kept together by his estate.21 Some of the estates’ holdings have been sold to local private collectors but key works from the two collections have left the island. Part of Campbell’s Cuban collection has, for instance, been auctioned at Christie’s, where his main Wifredo Lam (b. 1902, Sagua La Grande, Cuba; d. 1982, Paris) painting, Femme Cheval (1950), realized $2,415,000 in 2020.22

A lot of contextual material has also been lost in the dispersal of the Boxer and Campbell collections: The Burnett Webster house was sold and demolished to make way for a commercial complex, and Boxer’s house was also sold and is reportedly slated for demolition.23These developments have generated controversy in the Jamaican art world, as some feel that the Jamaican government should have stepped in to save these buildings and collections, which qualify as national treasures.24

The Wayne and Myrene Cox Collection

David Boxer positioned himself as chief arbiter and collector of Intuitive art, but he also supported other specialized collectors. Several, however, emerged independently and even challenged Boxer’s dominance of and orthodoxies about the Intuitives field. Wayne Cox, the director of a tax policy research organization in Minnesota, and his wife, Myrene Cox, an elementary school teacher, started vacationing regularly in Jamaica in the late 1980s and developed a passion for Intuitive art. Cox brokered close relationships with the artists and provided them with art materials and other support. He also commissioned some of the artists to recreate earlier work, which was inconsistent with the purist view of Intuitive art, which posited that such artists created without interference. Unlike Boxer, who was most interested in the psychological impulse behind such work, Cox took an ethnographic approach and focused on its place in the popular culture.

Cox’s entry into the specialized Intuitives sector resulted in a somewhat prickly, competitive relationship with Boxer, and other Intuitives collectors, but he quickly acquired a collection that rivaled Boxer’s Intuitive holdings in size, quality, and international reputation. He also developed relationships with artists who had eluded Boxer and helped to introduce them to Jamaican audiences. He acquired an important body of work by the visionary Revival artist-preacher Elijah (Geneva Mais Jarrett; b. 1952), who had exhibited at the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne in the early 1990s, but was largely unknown in Jamaica.25 Her work was first exhibited at the NGJ in the exhibition Intuitives III (2006), which highlighted work from the Cox collection. Cox also amassed a substantial archive of videotaped and transcribed interviews and documentary photographs.

Wayne and Myrene Cox acquired a house in St. Mary, a parish on the Jamaican North Coast, where they spent part of the year and where most of the collection and archives were kept and readily made available to visiting researchers, curators, and institutions such as the NGJ—it was not quite a private museum, but it gestured in that direction. Ill health and age intervened after a few years, however, and the Coxes sold the house and moved back full-time to the United States and now live in Florida. They kept part of their collection, but they have been selling some of their holdings in local and international sales and auctions.

An exhibition of selections from the Cox collection was held at the NGJ and focused on the yard exhibitions that are produced by Jamaican Intuitive artists. Titled Spiritual Yards: Home Ground of Jamaica’s Intuitives (2016–18), the exhibition was co-curated by Wayne Cox, O’Neil Lawrence, and me. Cox also offered part of this collection to the NGJ, and preliminary selections were then made with a view toward addressing gaps in the NGJ’s Intuitives collection. The donation was still being negotiated at the time of writing.26

III. Contemporary Art Collecting

The Jamaican banking crisis of the mid-1990s ended the high-interest era and the significant disposable incomes that came with it. The art market virtually collapsed in its wake and, as a result, very few commercial art galleries are active in Jamaica today. The local market has become a more informal and discrete one, in which direct sales by artists and private secondary sales prevail. New private collectors have appeared, but none have the public profile or influence of A. D. Scott, Aaron Matalon, David Boxer, or Wallace Campbell, and that appears to be a matter of choice. Most are prepared to lend to museum exhibitions and to facilitate reproductions, but the spirit of public philanthropy that informed some of the earlier collections is no longer evident.

While contemporary Jamaican art is thriving, with artists such as Ebony G. Patterson (b. 1981, Kingston, Jamaica) receiving unprecedented international critical recognition, the local market for such art is limited. Key artists have moved out of range for local collectors, and their work is generally not consistent with conservative local tastes and ideas about art. There are, however, some efforts to promote collecting contemporary art in an aspirational lifestyle context, as is evident in recent art acquisitions by several new hotels. The most ambitious of these has been the lobby collection of the AC Marriott Hotel in Kingston, which opened in 2019.

The AC Marriott Hotel collection was curated by art dealer Susanne Fredricks for the purpose of being integrated into the lobby’s interior design, along with design furniture, carefully positioned art books, and a clutter of decorative objects. It features a range of work, including large-scale sculptures and wall pieces by key contemporary artists such as Laura Facey, Leasho Johnson (b. 1984), Katrina Coombs (b. 1986, St. Andrew, Jamaica), Shoshanna Weinberger (b. 1973, Kingston, Jamaica), and Cosmo Whyte (b. 1982, St. Andrew, Jamaica). The collection is, at present, the only publicly accessible corporate collection in Jamaica that is specialized in contemporary art.

The initiative provides much-needed local support and exposure for Jamaica’s contemporary artists, yet there is a troubling dissonance between the critical content of some of the works, the stated intentions behind the collection, and the context in which they are exhibited. There is an accompanying catalogue brochure in which Fredricks states:

The AC Hotel is a global urban brand intended for the contemporary traveler – the optimistic and the curious; those who desire to explore a city’s pulse and culture…[I]t was our priority to curate a contemporary art collection that would speak to the deeper complexities of, and bring some fresh insights into Jamaica’s people and culture to guests, whilst maintaining the transcendental globality of the brand’s aesthetic.27

While the efforts to include local art and culture in this hotel environment are laudable, it is, as Fredricks acknowledges, part of the chain hotel’s carefully cultivated global brand. As such, the collection qualifies as an example of what Dean MacCannell called “staged authenticity,” a common strategy in tourism to package a selective and carefully sanitized semblance of authenticity to provide the visitors with a palatable and consumable sense of place, without however confronting them with its less agreeable aspects.28

The resulting tensions are poignantly illustrated by Cosmo Whyte’s Shotta II, a large mixed-media collage on paper that confronts those who enter the hotel via its main entrance.29 Shotta II interprets the famous photo-shoot scene in The Harder They Come (1972), the first Jamaican feature film to capture the international imagination as part of the international breakthrough of reggae. In this scene, the elusive rebel-gunman and singer Ivanhoe Martin (played by reggae singer Jimmy Cliff) has himself photographed at a Kingston photo studio, nattily dressed and with guns pointing defiantly at the viewer, and then sends the images to the press in order to taunt the authorities. The film stills of Ivanhoe Martin are among the most iconic images in Jamaica’s modern cultural history. They embody the defiance of Jamaica’s poor in the face of social invisibility, disempowerment, racism, and injustice, and represent the remarkable cultural energy that has emanated from this defiance and given Jamaica its global cultural visibility.

Cosmo Whyte’s Shotta II, which was commissioned for the collection, is part of a series, started around 2014, of life-size interpretations of these loaded images that reflects on the representational politics of race, class, masculinity, style, and visibility in the African diaspora. That Shotta II is mounted in the AC Marriott Hotel lobby has its peculiar ironies: In an earlier scene in The Harder They Come, Ivanhoe is chased away from the same sort of hotel in which his image now hangs. Whyte regards the central mounting of his work in this context as a critical provocation, pointedly related to such politics of access. The question arises however whether such a critical intervention is possible and effective in the highly staged, socially exclusionary context in which the work is mounted at the AC Marriott Hotel and, importantly, whether it is received as such by those who view it there. Irrespective of the intentions, it can be argued that this icon of popular black resistance merely adds a legitimizing veneer of cultural authenticity that is co-opted as an icon of aspirational urban chic, lifestyle branding, and neo-capitalist entrepreneurship. Ultimately, the inclusion of Shotta II in the AC Marriott Hotel lobby is a powerful illustration that art collecting and access to art remain uncomfortably couched in Jamaica’s unequal, contradiction- and tension-filled social dynamics.

IV. Conclusion

The history of art collecting in Jamaica not only mirrors the history of Jamaican art itself, it also illustrates how wealth, power, class, race, and other social factors have operated and been contested in postcolonial Jamaica. While this history has been punctuated with acts of deep generosity and civic-mindedness, it also reveals the divisive politics and power struggles that have shaped the Jamaican art world, as well as some of its ethical problems, such as the disregard for the conflict-of-interest issues that are common throughout the global art world but more sharply posed in small island societies. The history of art collecting is indeed a barometer of the Jamaican art ecology, revealing its areas of growth and potential as well as its pressure points.

One striking factor in this story is the tension between the realities of private, legal ownership—the narrow, “selfish” part of art collecting—and the philanthropic notion that art is collectively owned and that as part of the country’s cultural heritage, major examples of it must be accessible to the public. For the latter to be possible, however, there needs to be greater continuity in the major collections. The Jamaican government in 2020 indicated that it intends to establish a Register of Cultural Assets, in which items of national cultural significance would be listed with protective measures, such as first refusal rights for the State. The dispersal of the Boxer and Campbell collections, which included strong candidates for such a list, illustrates that this is indeed a matter of urgency. Whether such a policy is feasible is another matter, given the informal, poorly documented local art market and the inability of public collecting institutions to compete in the local or international markets. Such a policy is also likely to be resisted by collectors, as the underlying ethos of sharing ownership and public disclosure is not widely supported in the current context. While art collecting has indeed been a defining part of Jamaica’s artistic and cultural history, it does not automatically translate into the long-term sustainability of or access to the country’s artistic heritage, which is increasingly under threat.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, obtain permission from them, and to ensure that all credits are correct. PAMM has acted in good faith at all times on the best information available at the time of publication. PAMM apologizes for any inadvertent omissions, which will be corrected as soon as possible upon written notification.

- “About Us,” Institute of Jamaica website, https://instituteofjamaica.org.jm/?page_id=1013#page-content.

- For example, elsewhere in the Caribbean, the Royal Victoria Institute (today the National Museum and Art Gallery of Trinidad and Tobago) was established in 1892 in Trinidad, and the Barbados Museum & Historical Society was established in 1933.

- See “A Lively Meeting Of Jamaica Institute,” Daily Gleaner, January 30, 1936, p. 6; and “Annual Meeting Of The Institute Of Jamaica, Wednesday, Lively Indeed,” ibid., January 31, 1936, pp. 16–17, which includes a transcript of the meeting.

- See David Boxer, Edna Manley: Sculptor (Kingston: Edna Manley Foundation and National Gallery of Jamaica, 1990), p. 57.

- For a pointed analysis of these issues, see Krista Thompson, “‘Black Skin, Blue Eyes’: Visualizing Blackness in Jamaican Art, 1922–1944,” Small Axe 16, no. 2 (September 2004), pp. 1–31.

- The Jamaica School of Art was established in 1950 under the auspices of the IOJ. The Cultural Training Centre brought together on one campus the Jamaica Schools of Art, Dance, Drama and Music, and was renamed the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in 1995, when the institution started offering degrees.

- His position was redefined as chief curator in 1991, and he remained in that role until 2013, when he retired.

- Records of these early collection transactions are vague and contradictory.

- My reservations about the term and concept are on record, but I am using the term “Intuitive” here as it was used by Boxer and the NGJ to describe the narrow canon of self-taught, popular artists the institution has collected and promoted. See Veerle Poupeye, “Intuitive Art as a Canon,” Small Axe 24, no. 3 (October 2007), pp. 73–82.

- Jamaican Art, 1922–1982 was jointly organized by the NGJ and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, which toured the exhibition in the United States, Canada, and Haiti in 1982–85.

- Up to 2011, when the “ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums” was adapted by the Board, the NGJ sold works of art from its exhibitions and charged a 20 percent commission, which greatly added to its income.

- See Elizabeth Waugh, “Emergent Art and National Identity in Jamaica, 1920s to the Present” (Ph.D. diss., Queen’s University of Belfast, 1987).

- The work was donated by Valerie Facey, wife of the NGJ’s founding chairman, Maurice Facey. In 2012, Watson was eventually granted a major retrospective at the NGJ, which was curated by David Boxer. After more than two decades of overt antagonism, the two most powerful figures in the Jamaican art world after Edna Manley’s passing had finally reconciled.

- The BOJ is also home to the Jamaica Money Museum, and the curator of that museum has oversight of its art collection. See Bank of Jamaica, The Garden Party Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Bank of Jamaica (Kingston: Bank of Jamaica, 2001).

- Lieberman denied having made this statement, but he was nonetheless instrumental in cultivating donors to the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum.

- See, for instance, Annie Paul, “Legislating Taste: The Curator’s Palette,” Small Axe 4 (September 1998), pp. 65–83.

- The “ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums” (1987, 2004) sets minimum professional standards and encourages the recognition of values shared by the international museum community. Sections 5 and 7 are relevant here.

- The house was originally owned by Douglas Verity, a member of the nationalist intelligentsia, who then sold it to the director of tourism, John Pringle, in 1961. The Jamaican national anthem was written there.

- See, for instance, Edward M. Gómez. “A Passionate Patron,” Art & Antiques, https://www.artandantiquesmag.com/a-passionate-patron/; and Sara Rofino, “A Jamaican National Treasure: David Boxer discusses the Intuitive artists and his role in recognizing them,” Art & Auction (May 2017): 84–85.

- See “In Memoriam, Wallace Campbell, J.P., C.D. (1940–2020),” National Gallery of Jamaica Blog, May 7, 2020, https://nationalgalleryofjamaica.wordpress.com/2020/05/07/in-memoriam-wallace-campbell-j-p-c-d-1940-2020/. Though Campbell also collected Latin American art for a while, he decided to focus on the Caribbean and thus sold his Latin American holdings.

- It is understood that key works from Boxer’s collection are in storage at the NGJ, but there is no public clarity on their ownership status. On March 17, 2022, the NGJ made a post on its Facebook account on the occasion of Boxer’s birthday, which included the following statement: “We also wish to acknowledge the gifts to the National Collection from the David Boxer Estate through the Onyx Foundation. The gifts comprise works of arts, photographic works and books from his renowned collection.” This is, to date, the only public indication from the NGJ that there has been such a gift. A recent news report on a private function held at the NGJ on September 8 however indicated that more than thirty works were then donated (see “Works of the late Dr Boxer Finds [sic] New Home at the National Gallery, Jamaica Loop, September 15, 2022, https://jamaica.loopnews.com/content/works-late-dr-boxer-finds-new-home-national-gallery?fbclid=IwAR14nYBtBh_nGsSsUiFlM8qGxysiVY0vRHiqSCAeaHCLUK9pcKZ1iRbYmq4).

- See Wilfredo Lam, Femme Cheval, Christie’s, Live Auction 18183: Latin American Art, New York, 30 July 2020, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6275116.

- The Boxer garden was bulldozed after the sale in 2020, and the house appears to have been stripped of most of its fixtures.

- See, for instance, Veerle Poupeye, “Before It’s All Gone: Preserving Jamaica’s Architectural Heritage,” Perspectives (blog), June 20, 2020, https://veerlepoupeye.com/2021/06/20/before-its-all-gone-preserving-jamaicas-architectural-heritage/.

- I first became aware of Elijah’s work from a Collection de L’Art Brut catalogue in the early 1992, which had been sent to David Boxer, but do not recall seeing her work at the NGJ at that time. Wayne Cox has indicated that it was, in fact, Boxer who introduced him to her work around 1996 and had paintings by her in his office at the time (email March 4, 2023). This did however not result in her work being exhibited at the NGJ before 2006.

- The current status of the donation was confirmed by Wayne Cox (email March 4, 2023) and Roxanne Silent-Bucknor, Senior Director, NGJ (email March 6, 2023).

- Susanne Fredricks, Seeing Beyond Tropical Paradise. Brochure, AC Hotel Kingston, 2019, p.2

- See Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Schocken, 1976)

- For an image of Shotta II, see Cosmo Whyte artist website: http://www.cosmowhyte.com/playingmass